It flatters us to believe we’re the end result of an extraordinarily rare evolutionary event, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it isn’t so.

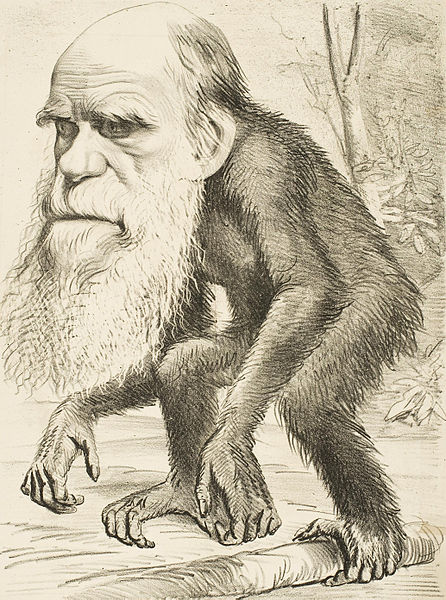

Stephen Jay Gould famously asked in 1989 if evolution would play out in the same way if we were able to “rewind the tape of life” to the Cambrian. He was sure it would not, that life was a cascading event that would have headed in a different direction, perhaps a very different one. Others vehemently disagree, thinking that variations would occur, sure, but given enough time, life would have wound up roughly in the same condition.

In a Nautilus article, Zach Zurich takes up the question, believing the answer may lie in outer space. An excerpt:

Does the rarity of any particular sequence of events imply that major shifts in evolution are unlikely to be repeated? The experiments suggest that’s true, but Conway Morris firmly answers, no. “You’d be daft to say that there aren’t accidents of one sort or another. The question is one of time scales,” he says. Given enough years and enough mutating genomes, he believes that natural selection will drive life toward the inevitable adaptations that best fit the organisms’ ecological niche, no matter the contingencies that occur along the way. He believes that one day, all of the E. coli in Lenski’s experiment would evolve to consume citrate, and that all of Liu’s viruses would eventually scale their adaptive Mount Everests. Further, those experiments were conducted in very simple and controlled environments that don’t come close to matching the complex ecosystems that life must adapt to outside the lab. It’s hard to say how real-world environmental pressures might have altered the results.

So far, the biggest shortcoming in all of the attempts to answer the “tape of life” question is that biologists can only draw conclusions based on just one biosphere—the Earth’s. An encounter with extra-terrestrial life would undoubtedly tell us more. Even though alien organisms may not have DNA, they’d likely show similar patterns of evolution. They would need some material that would be passed down to their descendants, which would guide the development of organisms and change over time. As Lenski says, “What’s true for E. coli is also true for some microbe anywhere in the universe.”

Therefore, the same interactions between convergence and contingency might play out on other planets. And if extraterrestrial life faces similar evolutionary pressures to life on Earth, future humans may discover aliens that have convergently evolved an intelligence like ours.5 On the other hand, if contingent events build on one another, driving the development of life down unique paths as Gould suggested, extra-terrestrial life may be extraordinarily strange.•