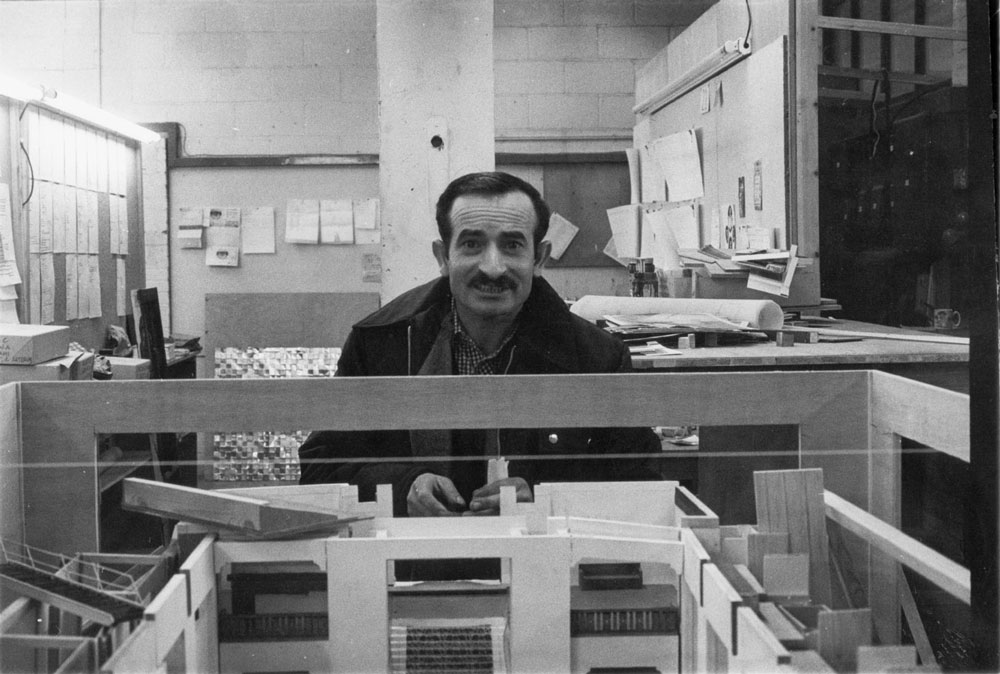

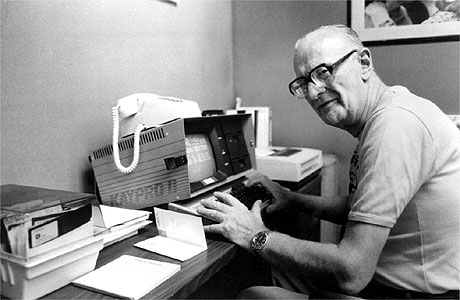

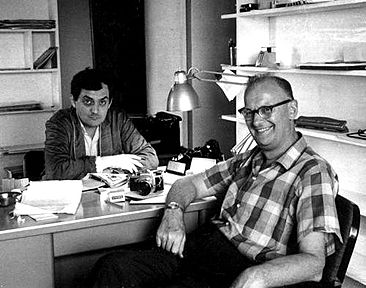

Stanley Kubrick was, I think, the greatest filmmaker of them all, more than Lang or Wilder or Godard or anyone. Living a private life in London, he grew into a mythical figure, although he didn’t put on airs, enjoyed American football and was amused by White Men Can’t Jump. But he was an eccentric guy whose film productions often lasted longer than many wars. It’s somehow no surprise that one of his longest-tenured employees was a Formula One race driver who had no previous movie experience before signing on for a stint on A Clockwork Orange. That man, Emilio D’Alessandro, has written a book about his 30-year odyssey with Kubrick.

From a Vice interview conducted by Rod Bastanmehr:

Vice:

What were some of the projects that you would hear him talk about that didn’t end up being filmed?

Emilio D’Alessandro:

Anytime we would be working on one film and we’d go down to a location, he would always be making notes or moves for another project. It was A.I. once, or Napoleon, which he really, really, really wanted to make. But he was always working on other projects while he was filming.

The thing he loved doing just as much [making movies] was the research. He had boxes and boxes of research done, so if one day he was able to finally make, say, this Napoleon movie, he would be ready. And I would keep it safe for him in case [producers] decided to actually do something with it. I would be ready to unearth it all myself. He never stopped researching, ever.

Vice:

Do you remember where you were when you heard he’d passed away? Were you with him?

Emilio D’Alessandro:

I’ll speak briefly because it really hurts me now, still. But yes, I was with him, I left him a note the night before on his desk like I always did. I said, “Everything is OK down in your office, your fax is clear, people got their messages. Please stay and have a rest, you’re very tired. You can come down in the afternoon—I’ll be here in the morning as usual.” Then unfortunately midday I got a phone call telling me that Stanley had died in the night. And I just screamed the biggest swear word, and I never swear. I had to drive to his house before I could believe it. And even when I got there and his wife took me by the hand to tell me, I still wasn’t sure it was real. And I drove back home that night not believing it. Sometimes I still don’t know if I do.•