“We are flummoxed by today’s nationalist, regressively anti-global sentiments only because we are interpreting politics through that now-obsolete television screen,” writes Douglas Rushkoff in an excellent Fast Company essay about the factious nature of the Digital Age. The post-TV landscape is a narrowcasted one littered with an infinite number of granular choices and niches. It’s empowering in a sense, an opportunity to vote “Leave” to everything, even a future that’s arriving regardless of popular consensus. It’s a far cry from not that long ago when an entire world sat transfixed by Neil Armstrong’s giant leap. Now everyone is trying to land on the moon at the same time–and no one can agree where it is. It’s more democratic this way, but maybe to an untenable degree, perhaps to the point where it’s a new form of anarchy.

Two excerpts follow from: 1) Rushkoff’s FC piece, and 2) Scott Timberg’s smart Salon Q&A with the media theorist.

From Rushkoff:

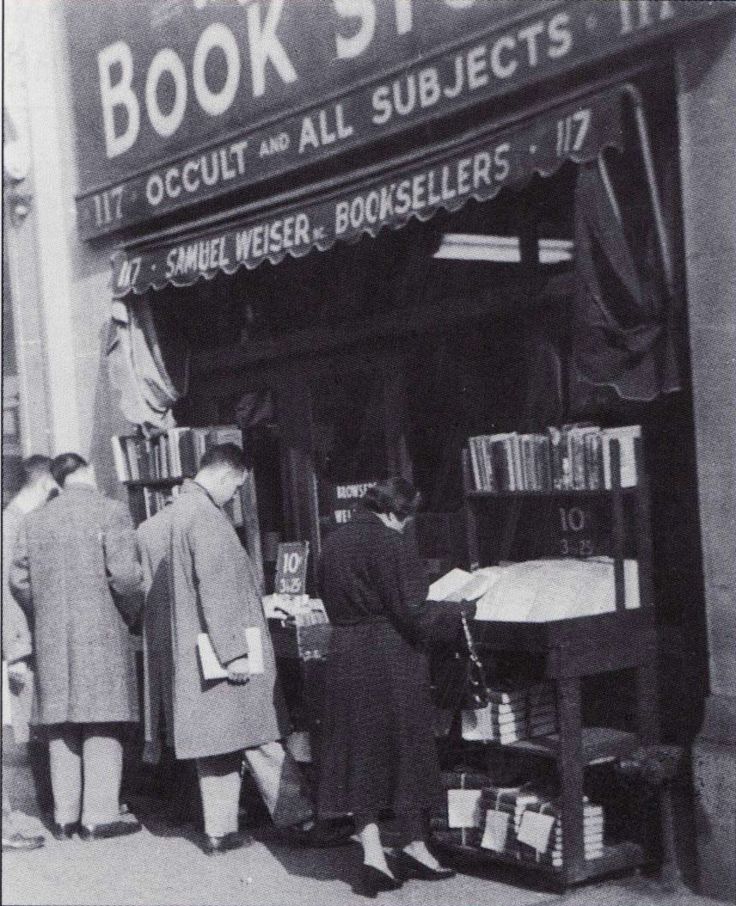

A media environment is really just the kind of culture engendered by a particular medium. The invention of text encouraged written history, contracts, the Bible, and monotheism. The clock tower in medieval Europe led to hourly wages and the time-is-money ethos of the industrial age. Different media environments encourage us to play different roles and to see, think, or act in particular ways.

The television era was about globalism, international cooperation, and the open society. TV let people see for the first time what was happening in other places, often live, as it happened. We watched the Olympics, together, by satellite. Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. Even 9-11 was a simultaneously experienced, global event.

Television connected us all and broke down national boundaries. Whether it was the British Beatles playing on The Ed Sullivan Show in New York or the California beach bodies of Baywatch broadcast in Pakistan, television images penetrated national divisions. I interviewed Nelson Mandela in 1994, and he told me that MTV and CNN had more to do with ending the divisions of apartheid than any other force.

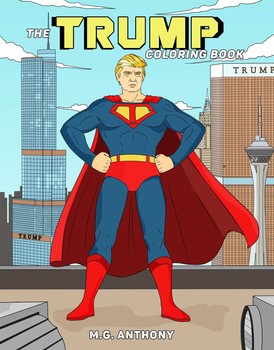

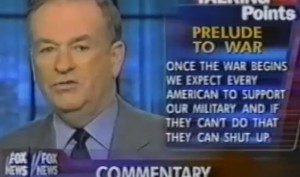

But today’s digital media environment is different. At the height of his media era, a telegenic Ronald Reagan could broadcast a speech in front of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin and demand that Gorbachev “tear down this wall.” Today’s ultimate digi-genic candidate Donald Trump demands that we build a wall to protect us from Mexicans.

This is because the primary bias of the digital media environment is for distinction.•

Timberg’s opening question:

Salon:

You argue that the support for Donald Trump and the puzzling Brexit vote both have to do, in important ways, with the dominance of the Internet. Not with anything political, but in the ways we communicate. How do you see these things related?

Douglas Rushkoff:

I don’t know if I’d blame the Internet as much as the idea that we’re in a digital media environment. The idea of being in a media environment, a technological environment, is really old – this guy [Lewis] Mumford is the one who came up with it…. And the beauty of that analysis is not that it says that one thing causes another – that the printing press led to the mechanization of world culture — but it sort of went hand in hand. We developed mechanical abilities, we made machines, then we took on some of the qualities of those machines. Because they’re around us, they’re part of the world we live in.

The thing I’ve been interested in is the shift from the television media environment, which we all grew up in, which was so globalist in spirit, and in funding — it promoted a global view and global markets and global simultaneity.

The digital media environment is so different in the way it’s structured and biased. We know that the algorithms in our social-media feeds tend to isolate us in our highly individuated factions or filter bubble — so we don’t interact with people with different ideas.

What are the biases of these technologies? All of these revolutions have been very discrete — we’re going to restore Egypt, we’re going to restore the caliphate — there’s this sense of nationalism and segmentation and difference.•