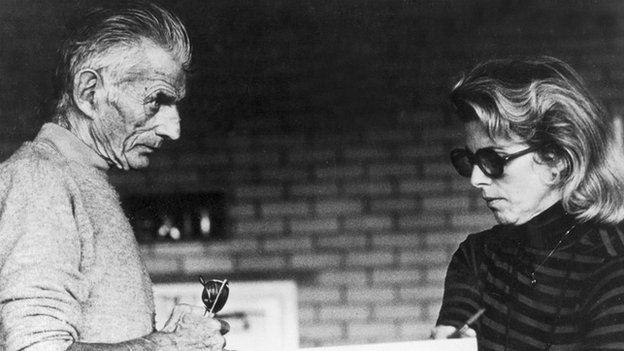

Before Barnes & Noble added couches and coffee and before those amenities were disappeared brick by brick and mortar by mortar by Amazon, there was a vast and very unwieldy version of the store near Rockefeller Center which sold remainder copies of Evergreen and Grove Press paperback plays for a buck. That’s how I came to Eugene Ionesco, Harold Pinter, Edward Albee, Bertolt Brecht and Samuel Beckett, the latter of whom was an absurdist as well as chauffeur to a pre-wrestling Andre the Giant. I can’t imagine a more trying dramatist to act for than Beckett, but Billie Whitelaw tried and succeeded. The go-to thespian for the Godot author just passed away. Here’s an excerpt from her Economist obituary:

“For 25 years she was the chosen conduit for the 20th century’s most challenging playwright, the author of Waiting for Godot She played Winnie in Happy Days, buried up to her waist in sand, carefully turning out her bag as she babbled away; the Second Woman in Play, the role in which Beckett first saw her at the Old Vic in 1964, enveloped in an urn with her face slathered with oatmeal and glue; May in Footfalls, communing with her absent mother while endlessly pacing a thin strip of carpet; and, in Rockaby, an ancient woman listening to her own voice as she slowly rocked herself to death.

She never pretended to understand these plays. She just thought of them as a state of mind, something she could recognise in herself. That was what Sam wanted: no interpretation, just perfection. If, almost unwittingly—for she wasn’t good at words, couldn’t spell and seldom read books—she replaced an ‘Oh’ with an ‘Ah,’ or paused minutely too long, upsetting the rhythm of his music, she would hear his murmured ‘Oh Lord!’ from the stalls, and see his head fall to his hands. He was always her best, gentlest and most exacting friend. In a way they were like lovers, walking arm in arm when she visited him in Paris, and rehearsing in her kitchen close up, she speaking directly into his pale, pale, powder-blue eyes, as he whispered the lines along with her. When he died, in 1989, she felt that part of her had been cut away.

Stutterer, chatterbox

It seemed unbelievable that it was her voice in Beckett’s mind when he wrote. It was nothing special to her. She had a Yorkshire accent, reflecting her Bradford childhood, but after a run of early TV typecasting in ‘trouble at t’mill’ dramas it had become residual, like her fondness for meat pies and Ilkley Moor. Her northern roots showed mostly in her liking for blunt, straight talk. At 11, after her father died, she had developed a stutter, which her mother thought might be cured by taking up acting. The cure worked so well that she became a staple on BBC radio’s Children’s Hour playing rough-voiced boys at ten shillings a time, and at 14 started to act for Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop. Any challenge or crisis, though, could bring the stutter back, together with paralysing stage-fright. When she played Desdemona to Laurence Olivier’s Othello at the National Theatre, in 1963, she could hardly stop her voice trembling.

Small wonder she was nervous. She had never read Shakespeare then, and had had no classical training. Her years in rep had mostly consisted of playing dizzy blondes, busty typists and maids.”

_____________________________

Whitelaw as “Winnie” in Happy Days: