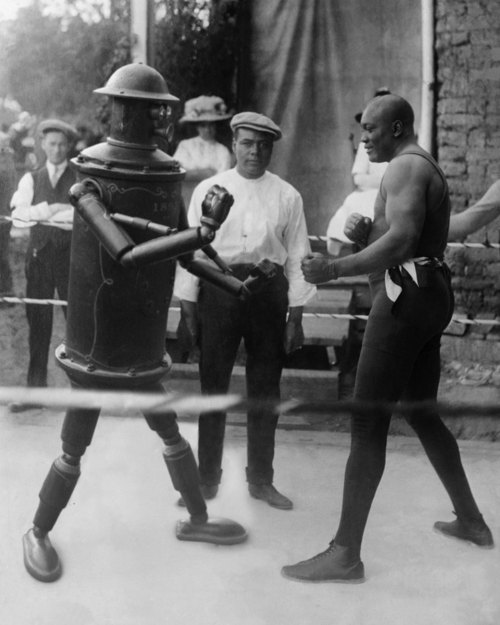

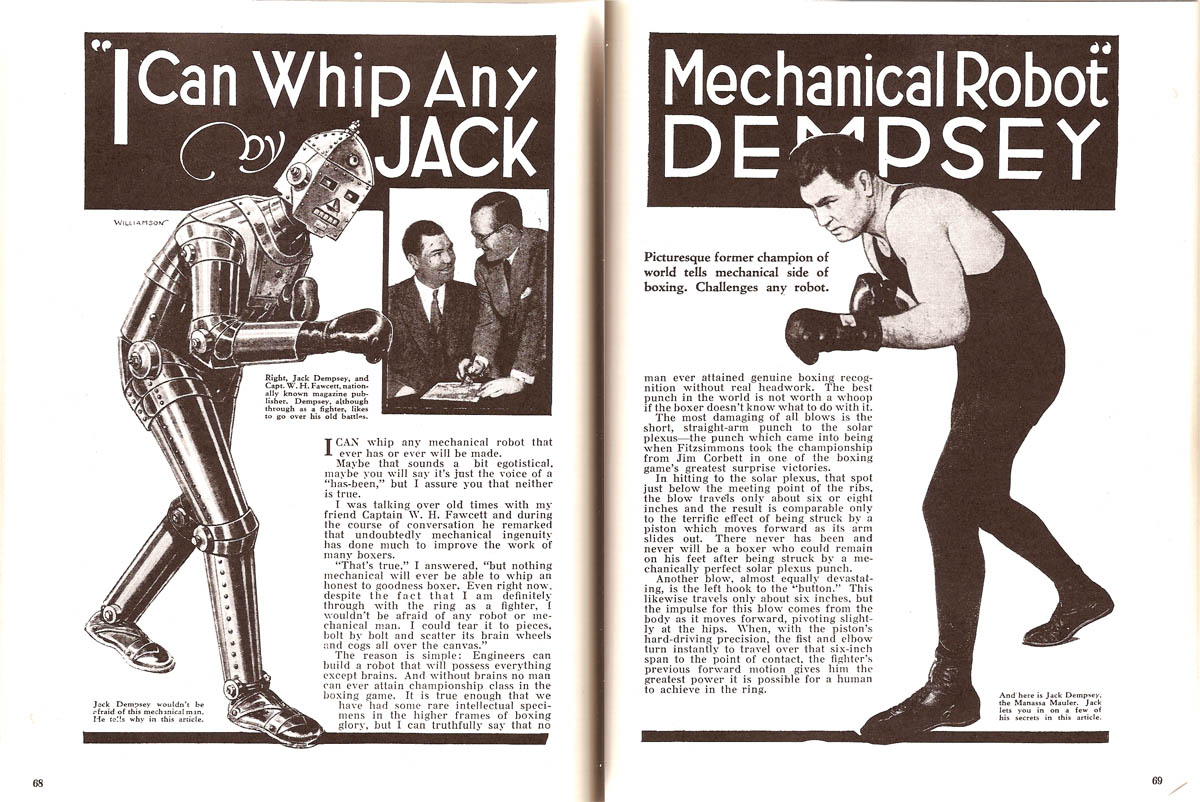

How do we reconcile a highly automated economy with a free-market one? If jobs of all skill levels emerge that can’t be outsourced beyond our species, we’ll be fine. But if average truly ls over, as Tyler Cowen and others have predicted, we could be in for some turbulence. Everyone and his brother can’t be quickly upskilled, and even if they could, there will be a limit to the number of driverless-car engineers needed. Abundance is great if we can figure out a good distribution system, something America has never perfected. If the macro financial picture is good but the micro is harsh, political solutions may become necessary.

From an PC World interview with The Wealth of Humans author Ryan Avent:

If this abundance of labor is indeed what is sparking global unrest, things will probably get a lot more chaotic before stability returns, unless the world embraces an Amish-style rejection of technology. So how should civilization proceed moving forward? Proposals include universal basic income (UBI), which is quite fashionable in Silicon Valley circles, or shortening the work week to four days.

“Eventually, we’re going to have to change the ways we do things so that people are working less and are also still able to buy the things they need—that would be where redistribution or basic income comes into the picture,” according to Avent. “There’s a couple of things to consider though. People don’t necessarily want to live in a world without work. Even though work is a drag, it creates structure for our day. It creates purpose and meaning. You can imagine that society would be kind of a messy place if nobody ever had to do anything. The other tricky thing is you need to find a way to pay for everything, which means that you have to tax somebody or create common ownership. Something that’s going to require a big political change.”

The big changes may be far in the future. Many of us may be able to wait out the big transformation, but where does that leave the next generation? Are they just completely screwed? As a parent of a young child, I am keenly interested in what skills—if any—will have any value in the decades to come.

“Those with a PhD in computer engineering will probably be okay. I don’t think that’s going to be something that goes away over the next few decades. The skills that will be applicable in a lot of parts of the economy will actually be the softer skills,” Avent says. “The ability to learn from others, to teach yourself new things, to get along in different cultural settings. Basically to be adaptive and be able to pick up new skills. That’s useful now, but in an environment where new sectors and new jobs are constantly be introduced will be critical to being successful.”•