There’s some question about how much futurists actually frame tomorrow and how much it reveals itself despite their input, but not quite knowing, we certainly need a strong representation of women and minorities in the mix, and we don’t have that. Maybe the underrepresented could suggest something other than jetpacks and trillionaires, which we don’t fucking need.

In her Atlantic piece “Why Aren’t There More Women Futurists?” Rose Eveleth points out that the media’s go-to talking heads in this unlicensed, nebulous discipline are the male figures who dominate science and tech. Their dreams of utopia are often homogenous, corporate and patriarchal. It’ll be difficult to diversify futurism without attacking society’s underlying sexism.

Eveleth’s opening:

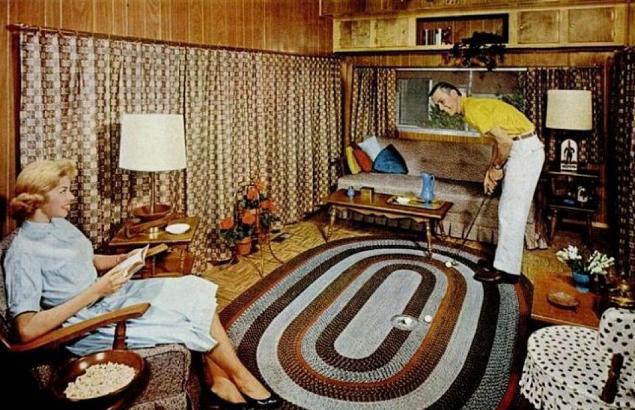

In the future, everyone’s going to have a robot assistant. That’s the story, at least. And as part of that long-running narrative, Facebook just launched its virtual assistant. They’re calling it Moneypenny—the secretary from the James Bond Films. Which means the symbol of our march forward, once again, ends up being a nod back. In this case, Moneypenny is a send-up to an age when Bond’s womanizing was a symbol of manliness and many women were, no matter what they wanted to be doing, secretaries.

Why can’t people imagine a future without falling into the sexist past? Why does the road ahead keep leading us back to a place that looks like the Tomorrowland of the 1950s? Well, when it comes to Moneypenny, here’s a relevant datapoint: More than two thirds of Facebook employees are men. That’s a ratio reflected among another key group: futurists.

Both the World Future Society and the Association of Professional Futurists are headed by women right now. And both of those women talked to me about their desire to bring more women to the field. Cindy Frewen, the head of the Association of Professional Futurists, estimates that about a third of their members are women. Amy Zalman, the CEO of the World Future Society, says that 23 percent of her group’s members identify as female. But most lists of “top futurists” perhaps include one female name. Often, that woman is no longer working in the field.•