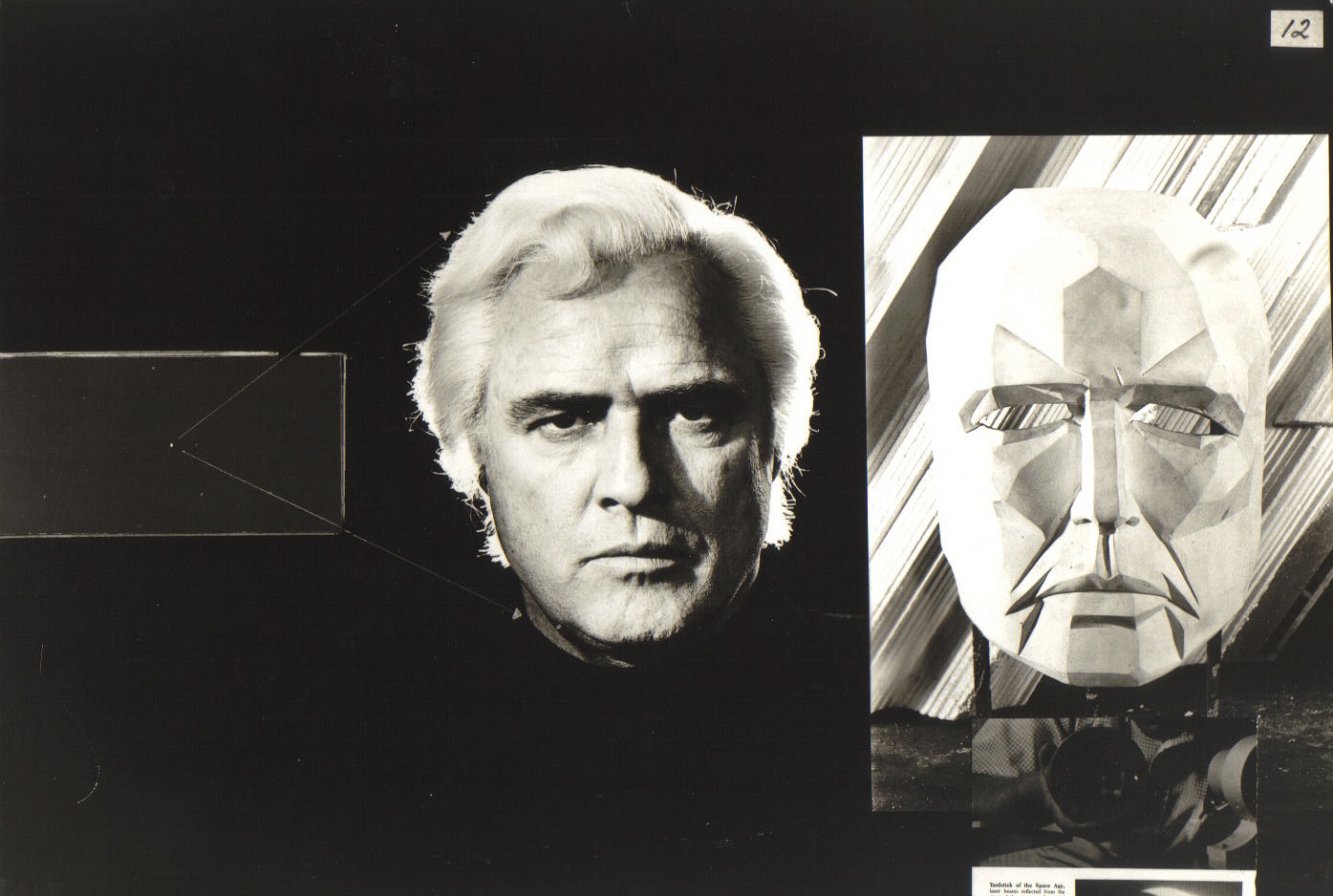

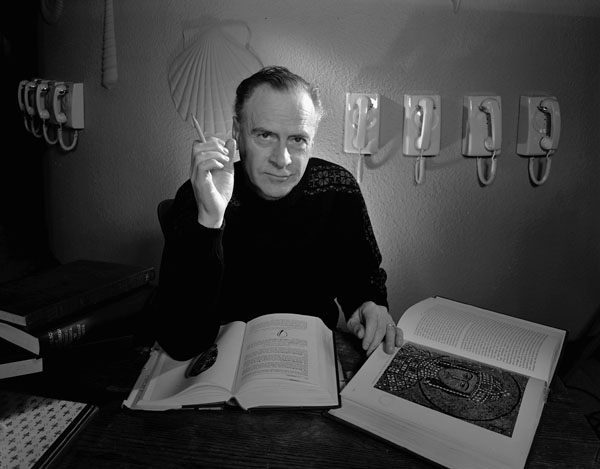

Easily the best article I’ve read about E.L. Doctorow in the wake of his death is Ron Rosenbaum’s expansive Los Angeles Review of Books piece about the late novelist. It glides easily from Charles Darwin to Thomas Nagel to the hard problem of consciousness to the “electrified meat” in our skulls to the “Jor-El warning” in Doctorow’s final fiction, Andrew’s Brain. That clarion call was directed at the Singularity, which the writer feared would end human exceptionalism, and, of course, it would. More a matter of when than if.

An excerpt:

Not to spoil the mood but I feel a kind of responsibility to pass on Doctorow’s Jor-El warning, even if I don’t completely understand it. I would nonetheless contend that — coming from a person as steeped as he is in the contemplation of the Mind and its possibilities, the close reading of consciousness, of that twain of brain and mind and the mysteries of their relationship — attention should be paid. It seemed like a message he wanted me to convey.

I asked him to expand upon the idea voiced in Andrew’s Brain that once a computer was created that could replicate everything in the brain, once machines can think as men, when we’ve achieved true “artificial intelligence” or “ the singularity” as it’s sometimes called, it would be “catastrophic.”

“There is an outfit in Switzerland,” he says. “And this is a fact — they’re building a computer to emulate a brain. The theory is, of course, complex. There are billions of things going on in the brain but they take the position that the number of things is finite and that finally you can reach that point. Of course there’s a lot more work to do in terms of the brain chemistry and so on. So Andrew says to Doc ‘the twain will remain.’

“But later he has this revelation because he’s read, as I had, a very responsible scientist saying that it was possible someday for computers to have consciousness. That was said in a piece by a very respected neuroscientist by the name of Gerald Edelman. So the theory is this: If we do ever figure out how the brain becomes what we understand as consciousness, our feelings, our wishes, our desires, dreams — at that point we will know enough to simulate with a computer the human brain — and the computer will achieve consciousness. That is a great scientific achievement if it ever occurs. But if it does, all the old stories are gone. The Bible, everything.”

“Why?”

“Because the idea of the exceptionalism of the human mind is no longer exceptional. And you’re not even dealing with the primary consciousness of animals, of different degrees of understanding. You’re talking about a machine that could now think, and the dominion of the human mind no longer exists. And that’s disastrous because it’s earth-shaking. I mean, imagine.”•