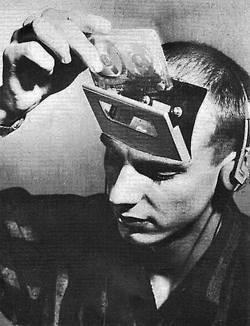

Robin Hanson has identified what he believes to be an alternative to the incremental growth of machine superintelligence through AI with the idea of brain emulations or ems, scanned copies of human brains that are downloaded into computers and then in some cases given robot bodies. You would choose the greatest minds and allow machines to improve their knowledge at a head-spinning clip, intelligence exploding at ahead-spinning clip. Armies of ems could take over all the work, the whole economy, industries could rise and fall in days, output would be increased at heretofore unimaginable speed. Humans wouldn’t need to labor anymore and post-scarcity will have arrived. We’ve moved immensely culturally from foragers to Digital Age denizens with no explosion of intelligence, so the changes to life on Earth with one would be seismic. Hanson believes it all could occur within a century.

I’m not a physicist or economist like Hanson, but I believe his timeframe is wildly aggressive. Let me accept his prediction wholly, however, to ask some questions. What if we don’t wisely choose our brains to emulate? As I posted yesterday, Russian scientists carved the late Vladimir Lenin’s brain into more than 30,000 pieces searching for the secret of his intellectual powers. If the technology was available then, they certainly would have chosen the Bolshevik leader to make millions of ems from. Lenin wouldn’t be my first choice to emulate, but he would be a far better choice than, say, Stalin, who would have been the chosen one for the next generation. Hitler’s brain would have been replicated many times over in the mass delusion of Nazi Germany. In North Korea today, the Dear Leader would be the brain to embody inside of robots.

Even the best among us have terrible ideas we have yet to admit or realize. For example, the American Founding Fathers allowed for slavery and didn’t permit women to vote. Every age has its sins, from colonialism to wealth inequality, and its only with a wide variety of minds do we come to realize our wrongs, and often those who speak first and loudest about injustices (e.g. Abolitionists) are deemed “undesirables” who would never be selected for “mass production” of their minds. Wouldn’t choosing merely the “best and brightest” be a dicey form of eugenics to the nth degree?

Even further, if ems truly become possible at some point, wouldn’t they also be ripe for destabilization, especially in a future that’s become that technologically adept? Wouldn’t a terrorist organizations be able to create a battalion of like-minded beheaders? Isn’t it possible that a lone wolf who wanted to unloose mayhem could hatch a “start-up” in his garage? You can’t refuse to create all new tools because they can become weapons, but wouldn’t ems be different in a dangerous way on a whole other level?

Excerpts follow from two pieces about Hanson’s new book, The Age of Em: 1) Steven Poole’s Guardian review, and 2) A Q&A with the author by James Pethokoukis of the American Enterprise Institute.

Poole’s opening:

In the future, or so some people think, it will become possible to upload your consciousness into a computer. Software emulations of human brains – ems, for short – will then take over the economy and world. This sort of thing happens quite a lot in science fiction, but The Age of Em is a fanatically serious attempt, by an economist and scholar at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, to use economic and social science to forecast in fine detail how this world (if it is even possible) will actually work. The future it portrays is very strange and, in the end, quite horrific for everyone involved.

It is an eschatological vision worthy of Hieronymus Bosch. Trillions of ems live in tall, liquid-cooled skyscrapers in extremely hot cities. Most of them are “very able focused workaholics”, who “respect and trust each other more” than we do.

Some ems will have robotic bodies; others will just live in virtual reality all the time. (Ems who are office workers won’t need bodies.) Some ems will run a thousand times faster than human brains, so having a subjective experience of much-expanded time. (Their bodies will need to be very small: “At this scale, an industry-era city population of a million kilo-ems could fit in an ordinary bottle.”) Others might run very slowly, to save money. Ems will congregate in related “clans” and use “decision markets” to make important commercial and political choices. Ems will work nearly all the time but choose to remember an existence that is nearly all leisure. Some ems will be “open-source lovers”; all will be markedly more religious and also swear more often. The em economy will double every month, and competition will drive nearly all wages down to subsistence levels. Surveillance will be total. Fun, huh?•

From the American Enterprise Institute:

Question:

The book is not about us; it’s about the ems, about their life, their culture. You make a lot of speculations; you draw a lot of conclusion about what the life of these synthetic emulations are like. So how can you do that?

Robin Hanson:

I am taking our standard, accepted theories in a wide variety of areas and apply them to this key scenario: what happens if brain emulations get cheap?

Honestly, most people like the future as a place to set fantasy stories. In the past, we used to have far away places as our favorite place to set strange stories where strange things could happen but then we learned about all the far away places. So then we switched to the future, it was the place we could set strange stories. And because you could say, well no one can show my strange story is wrong about the future because no one can know about the future, so it’s become an axiom to people that the future must be unknowable, therefore we can set strange stories there. But, if we know about the world today and we use theories about the world today to understand the past, those same basic theories can also apply to the future, so my exercise is theory.

I am taking our standard, accepted theories in a wide variety of areas and apply them to this key scenario: what happens if brain emulations get cheap? And if we have reliable theory to help us understand the world around us and to help us understand the past, those same theories should be able to describe the future

Question:

Give a couple examples and how that gives you some insights into what this new world of synthetic emulations would be like for them.

Robin Hanson:

First of all, I’m just using supply and demand to describe how wages change. I use the same supply and demand theory of wages that we use to understand why wages are higher here than in Bangladesh or why wages were low a thousand years ago. That same theory can say why wages would be high in the future.

I also use simple physics: for examples these emulations can run at different speeds, I can use computer science to say if they run twice as fast they should cost twice as much, because they are very parallel programs. I can also use physics to say that if they have bodies to match the speeds of their minds, if their mind runs twice as fast, their body needs to be twice as short in order to feel natural to that mind. So very fast emulations, very small bodies. I can use our standard theory of cities and urban concentrations to think about whether ems concentrate in a few big cities or lots of smaller cities.

Today, our main limitation of having a lot of us in one big city is traffic congestion. The bigger the city the more time people spend in traffic, and that limits our cities. Emulations can interact with each other across a city using virtual reality, which is much cheaper so they face much less traffic congestion, so I use that to predict that they live in a small number of very big, dense cities.

Question:

And we’re not talking about an alien intelligence or a super intelligence, but a synthetic duplication of a regular human brain or human mind, therefore it would work in some sort of predictable manner.

Robin Hanson:

Exactly, so we know a lot of things about humans, when they work they need breaks and they need weekends and they need vacations, so we can say these emulations will work hard because it is a competitive world, but they still will take breaks, and they’ll take the evening off to sleep.

These are all things we know about human productivity; these emulations are still very humans psychologically.

Question:

I was reading a review of the book and someone said, you could have a whole factory of “Elon Musk” workers, all very smart, and those ems would go out after work to a bar or a club and they would see an em of Taylor Swift. So Elon Musk #1,000,400,000 or something could be listening to Taylor Swift # 2,000,100,000. So it’s a duplication of human society but with some rules changed.

Robin Hanson:

Right, so it’s in the uncanny valley where it’s strange enough to be different but familiar enough to be strange. If it were completely alien, it would just but weird and incomprehensible, but it’s not.

Question:

Is this something you think the science supports and that could happen over the next 100 years or so?

Robin Hanson:

Right.•