In an excellent BBC Future piece, Rachel Nuwer attempts to weigh how close the West is to societal collapse, an implosion that would occur, if it does, not because of scarcity but due to our system, plagued by wealth inequality, failing at distribution.

Climate change may also play an important role, with a potential refugee crisis that will dwarf Syria’s tragedy, the relatively “dry” states overwhelmed by the inundation. Or perhaps the luckier lands will meet with disaster by trying to build a wall to keep the future out. Either reality is fraught.

The writer relies in part on the computer models of systems scientists to gauge if ecological strain and economic stratification will topple us, some of which suggest the latter factor could do us in entirely on its own, though the more likely scenario would be a confluence of unfortunate circumstances.

Of course, models have long predicted that great societies, actual or virtual, would soon be ghost towns. In 2014, two young Princeton academics applied epidemiology to social networks to make a prognostication I’m sure they’d like wiped from the Internet: By 2017, Facebook would lose 80% of its users. Missed by that much.

Still, sooner or later, entropy will leave a bruise.

The opening:

The political economist Benjamin Friedman once compared modern Western society to a stable bicycle whose wheels are kept spinning by economic growth. Should that forward-propelling motion slow or cease, the pillars that define our society – democracy, individual liberties, social tolerance and more – would begin to teeter. Our world would become an increasingly ugly place, one defined by a scramble over limited resources and a rejection of anyone outside of our immediate group. Should we find no way to get the wheels back in motion, we’d eventually face total societal collapse.

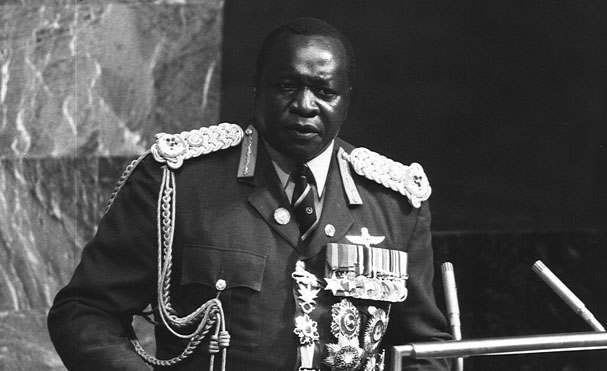

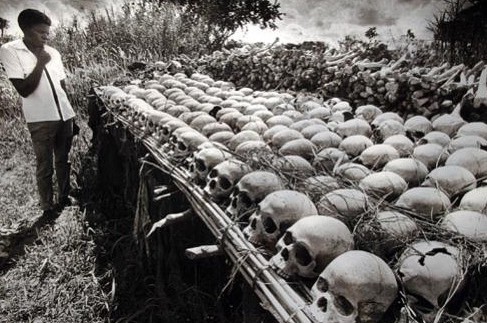

Such collapses have occurred many times in human history, and no civilisation, no matter how seemingly great, is immune to the vulnerabilities that may lead a society to its end. Regardless of how well things are going in the present moment, the situation can always change. Putting aside species-ending events like an asteroid strike, nuclear winter or deadly pandemic, history tells us that it’s usually a plethora of factors that contribute to collapse. What are they, and which, if any, have already begun to surface? It should come as no surprise that humanity is currently on an unsustainable and uncertain path – but just how close are we to reaching the point of no return?•