In Peter Aspden’s Financial Times profile of clock-watcher and turntablist Christian Marclay, the talk turns to how digital technology has refocused our attention from product to production, the process itself now a large part of the show. An excerpt:

When did the medium become more important than the message? Philosopher Marshall McLuhan theorised about the relationship between the two half a century ago — but it is only today that we seem to be truly fascinated by the processes involved in the creation of contemporary art and music, rather than their end result. Nor is this just some philosophical conceit; it extends to the lowest level of popular culture: what are the TV talent shows The X Factor and The Voice if not obsessed by the starmaker machinery of pop, rather than the music itself?

There are two reasons for this shift in emphasis. The first is technology. When something moves as fast and as all-consumingly as the digital revolution, it leaves us in its thrall. Our mobile devices sparkle more seductively than what they are transmitting. The speed of information has more of a rush than the most breakneck Ramones single.

Digital tools also enable the past to be appropriated in thrilling new forms — “The Clock” would not have been possible in an analogue age. Marclay has said he developed calluses on his fingers from his work in the editing suite, echoing the injuries once suffered by the hoariest blues guitarists. “The Clock” is a reassemblage of found objects: that is not a new phenomenon in artistic practice, but never has it been taken to such popular and imaginative heights.

It is the art of the beginnings of the digital age: not something entirely new, but a reordering of great, integral works of the past. “A record is so tangible,” says Marclay when I ask him about his vinyl fixation. “A sound file is nothing.” Sometimes, I say, it feels as if he has taken all the passions of my youth — records, movies, comic books — and thrown them all in the air, fitting them back together with technical bravura and, in so doing, investing them with new, hidden meanings. I ask if his art is essentially nostalgic. “I don’t think it is,” he replies firmly. “But there is a sense of comfort there. These are things we grew up with. They are familiar. And that is literally the right word: they are family.”

The second, less palatable, reason for the medium to overshadow the message is because of a loss of cultural confidence. We are not sure that the end result of whatever it is we are producing with such spectacular technological support can ever get much better than Pet Sounds, or Casablanca, or early Spider-Man. This does lead to nostalgia; not just for the old messages but for the old media, too. Marclay tells me there is a cultish following for audio cassettes, as if the alchemy of that far-from-perfect technology will help reproduce the magic of its age.•

______________________________

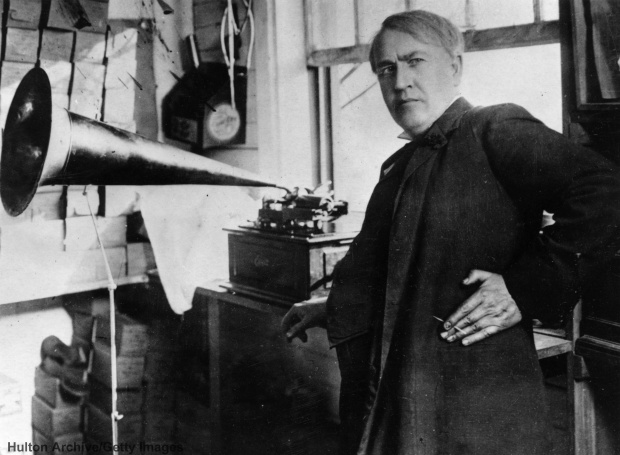

Marclay re-making music in 1989.