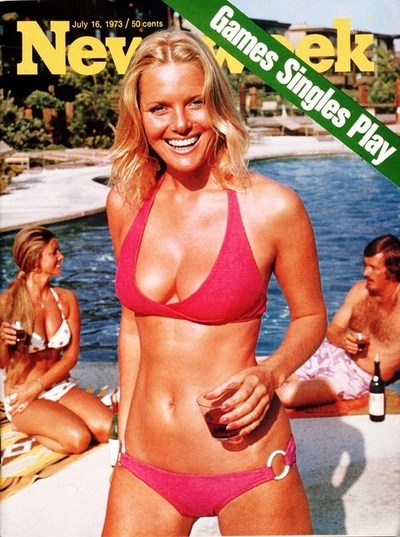

Americans are pretty much cradle-to-grave adolescents now, regardless of career, marriage or children. Our obsession with youth, which began fairly spontaneously in the 1960s, was commodified the following decade, and there’s since been no retreat. That’s probably because being elderly is the leading cause of death. An article from the July 16, 1973 edition of Newsweek, “Games Singles Play,” examines the swinging scene of the 1970s, presenting a portrait of a nation shifting and free enterprise pivoting to accommodate the recalibration, while mixing in some foolish phrases like “post-Pepsi generation” and “swingles.” The opening:

It all began modestly enough. An unmarried New York City perfume salesman named Alan Stillman decided that the coolest way to meet the stewardesses in his neighborhood would be to buy a broken-down beer joint, jazz it up with Tiffany lamps and mod young waiters and christen it–with an eye toward attracting the career crowd–the T.G.I.F. (for Thank God It’s Friday). Within one week, the police had to ring Fridays (as it quickly became known) with barricades to handle the nightly hordes of young singles on the make. Hundreds of blatantly imitative emporiums soon opened their doors in scores of major cities–and an industry was born. What began largely as a salesman’s mating ploy has triggered an explosion of singles-only institutions: singles apartment complexes, singles cruises, singles weekends at resort hotels, singles clubs for every persuasion from vegetarians to occultists. Within just eight years, singlehood has emerged as an intensely ritualized–and newly respectable–style of American life.

Until recently, the term “single” usually connoted a lonely heart, a temporary loser whose solitary status was simply a way station on the passage to matrimony. The lonely hearts may still bleed, but for millions of other under-35, middle-class folk, singlehood has become a glittering end in itself–or at least a newly prolonged phase of post-adolescence. And while much of the younger singles’ fun and gamesmanship is also tinged with frustrations, loneliness and quiet desperation, many of the players contend that they have found the Good Life. “The singles ‘skindrome’ is not a search,” insists Tom Whitehead, a bearded Atlanta bachelor. “It’s entire premise is to live life to the fullest.”

That glowing prospect appears to be attracting an increasing number of believers. Of the U.S.’s 48 million single adults, 12.7 million are between the ages of 20 and 34–a massive 50 per cent jump for that age group since 1960. The accelerating divorce rate has also brought swarms of young converts into the singles fold, where they now tend to remain for far longer periods. Indeed, the number of under-35s who have been divorced but have not remarried (1.3 million) is more than double the figure of a decade ago. To a growing corps of social analysts, the trend seems to signal a profound shift in mating patterns. One sociologist has gone so far as to predict that “eventually, married people could find themselves living in a totally singles-oriented society.”

The singles tide is being propelled by several powerful subcurrents. Dr. Paul Glick, a population analyst for the Census Bureau, believes that the economic and sexual liberation of the young working woman is diminishing her need for the “sacred halo of marriage.” As evidence, Glick points to the proportion of women who remain unmarried in their 20s has soared by a full third since 1960. Another student of the singles subculture, Washington D.C. sociologist Dr. Joyce Starr, feels that today’s post-Pepsi generation may be the first to place the search for self-identity above the quest for a mate. “They’re discovering how little college adds to emotional development and self-confidence,” says Dr. Starr. “The single state is now the only place where they can feel themselves out.”

Marriage remains the statistical norm, of course, but unprecedented affluence and mobility have allowed today’s single to reject settling for just any old match. “We looked at our parents’ marriages,” explains a young journalist, “and decided to hold out for something a hell of a lot better. In a way, we’re sort of middle-class revolutionaries.” At the same time, the sheer number of singles, meshed with the media’s seductive imagery (singles who swing are jauntily dubbed “swingles”), is gradually revising society’s view of of its unwed members. Benjamin Franklin once described the unmarried person as “the odd half of a pair of scissors.” But today, notes Columbia University anthropologist Herbert Passin, “it is finally becoming possible to be both single and whole. For the first time in human history the single condition is being recognized as an acceptable adult life-style for anyone.”

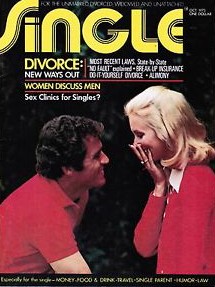

Enter the singles entrepreneur. The discovery that America’s unmarried population now wields an annual spending power of some $40 billion has spawned an explosive growth industry aimed at satisfying the unwed’s every whim. Each week seems to bring a fresh twist on the merchandising theme. Chateau D’Vie, the nation’s first year-round country club designed exclusively for singles, recently opened in a New York suburb–and signed up 1,000 eager applicants (at $550 a year) within four weeks. “We were even able to screen out all the losers, fatties and dogs,” chuckles Chateau co-owner Richard Kovner. And last month marked the debut of a new weekly magazine called Single, which will offer advice on coping and coupling from contributors as disparate as Bella Abzug and futurologist Herman Kahn. “Singles are a runaway statistic,” gloats Single publisher Hy Steirman, who ordered a press run of 750,000 for his inaugural issue.”•