In relation to the recent Paul Ehrlich post, here’s the opening of an excellent 1990 New York Times article by John Tierney about a wager the Malthusian made about the population bomb with his fierce academic rival, the cornucopian economist Julian L. Simon:

In 1980 an ecologist and an economist chose a refreshingly unacademic way to resolve their differences. They bet $1,000. Specifically, the bet was over the future price of five metals, but at stake was much more — a view of the planet’s ultimate limits, a vision of humanity’s destiny. It was a bet between the Cassandra and the Dr. Pangloss of our era.

They lead two intellectual schools — sometimes called the Malthusians and the Cornucopians, sometimes simply the doomsters and the boomsters — that use the latest in computer-generated graphs and foundation-generated funds to debate whether the world is getting better or going to the dogs. The argument has generally been as fruitless as it is old, since the two sides never seem to be looking at the same part of the world at the same time. Dr. Pangloss sees farm silos brimming with record harvests; Cassandra sees topsoil eroding and pesticide seeping into ground water. Dr. Pangloss sees people living longer; Cassandra sees rain forests being decimated. But in 1980 these opponents managed to agree on one way to chart and test the global future. They promised to abide by the results exactly 10 years later — in October 1990 — and to pay up out of their own pockets.

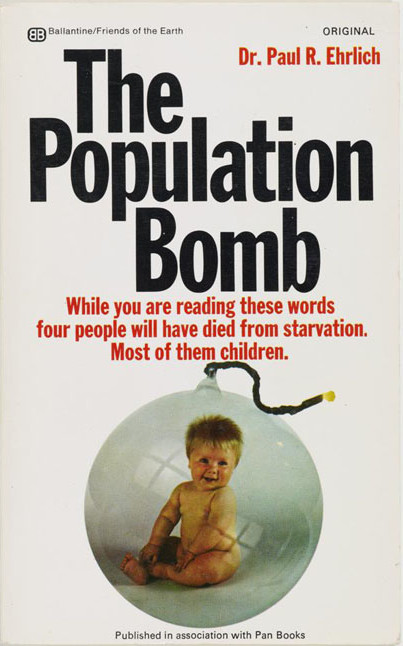

The bettors, who have never met in all the years they have been excoriating each other, are both 58-year-old professors who grew up in the Newark suburbs. The ecologist, Paul R. Ehrlich, has been one of the world’s better-known scientists since publishing The Population Bomb in 1968. More than three million copies were sold, and he became perhaps the only author ever interviewed for an hour on The Tonight Show. When he is not teaching at Stanford University or studying butterflies in the Rockies, Ehrlich can generally be found on a plane on his way to give a lecture, collect an award or appear in an occasional spot on the Today show. This summer he won a five-year MacArthur Foundation grant for $345,000, and in September he went to Stockholm to share half of the $240,000 Crafoord Prize, the ecologist’s version of the Nobel. His many personal successes haven’t changed his position in the debate over humanity’s fate. He is the pessimist.

The economist, Julian L. Simon of the University of Maryland, often speaks of himself as an outcast, which isn’t quite true. His books carry jacket blurbs from Nobel laureate economists, and his views have helped shape policy in Washington for the past decade. But Simon has certainly never enjoyed Ehrlich’s academic success or popular appeal. On the first Earth Day in 1970, while Ehrlich was in the national news helping to launch the environmental movement, Simon sat in a college auditorium listening as a zoologist, to great applause, denounced him as a reactionary whose work “lacks scholarship or substance.” Simon took revenge, first by throwing a drink in his critic’s face at a faculty party and then by becoming the scourge of the environmental movement. When he unveiled his happy vision of beneficent technology and human progress in Science magazine in 1980, it attracted one of the largest batches of angry letters in the journal’s history.

In some ways, Simon goes beyond Dr. Pangloss, the tutor in Candide who insists that “All is for the best in this best of possible worlds.” Simon believes that today’s world is merely the best so far. Tomorrow’s will be better still, because it will have more people producing more bright ideas. He argues that population growth constitutes not a crisis but, in the long run, a boon that will ultimately mean a cleaner environment, a healthier humanity and more abundant supplies of food and raw materials for everyone. And this progress can go on indefinitely because — “incredible as it may seem at first,” he wrote in his 1980 article — the planet’s resources are actually not finite.•