George Ripley had the best of intentions.

In 1841, the Transcendentalist social reformer and journalist founded the short-lived Massachusetts collective, Brook Farm. Established along with other progressives of his day, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, the communal space was to be a haven for workers who longed for industry, not toil. The profits would be shared fairly. But there were no profits, just debts. Brook Farm didn’t experience a moral collapse, but a financial one. The kinetic never was able to match the potential. Hawthorne got a a novel out of the experiment (The Blithedale Romance), but what did Ripley gain from this bitter failure apart from heartbreak? He said of the experience at its end in 1846: “I can now understand how a man would feel if he could attend his own funeral.”

But here’s the thing: Maybe Brook Farm wasn’t the unmitigated disaster it seemed at the time. Massachusetts today is the leader among American states in both education and health care. Ripley can’t claim responsibility for those developments, but perhaps he and other idealists help lay a foundation for the state’s magnanimity. Utopias can distort reality, yes, but they give us a goal in the distance.

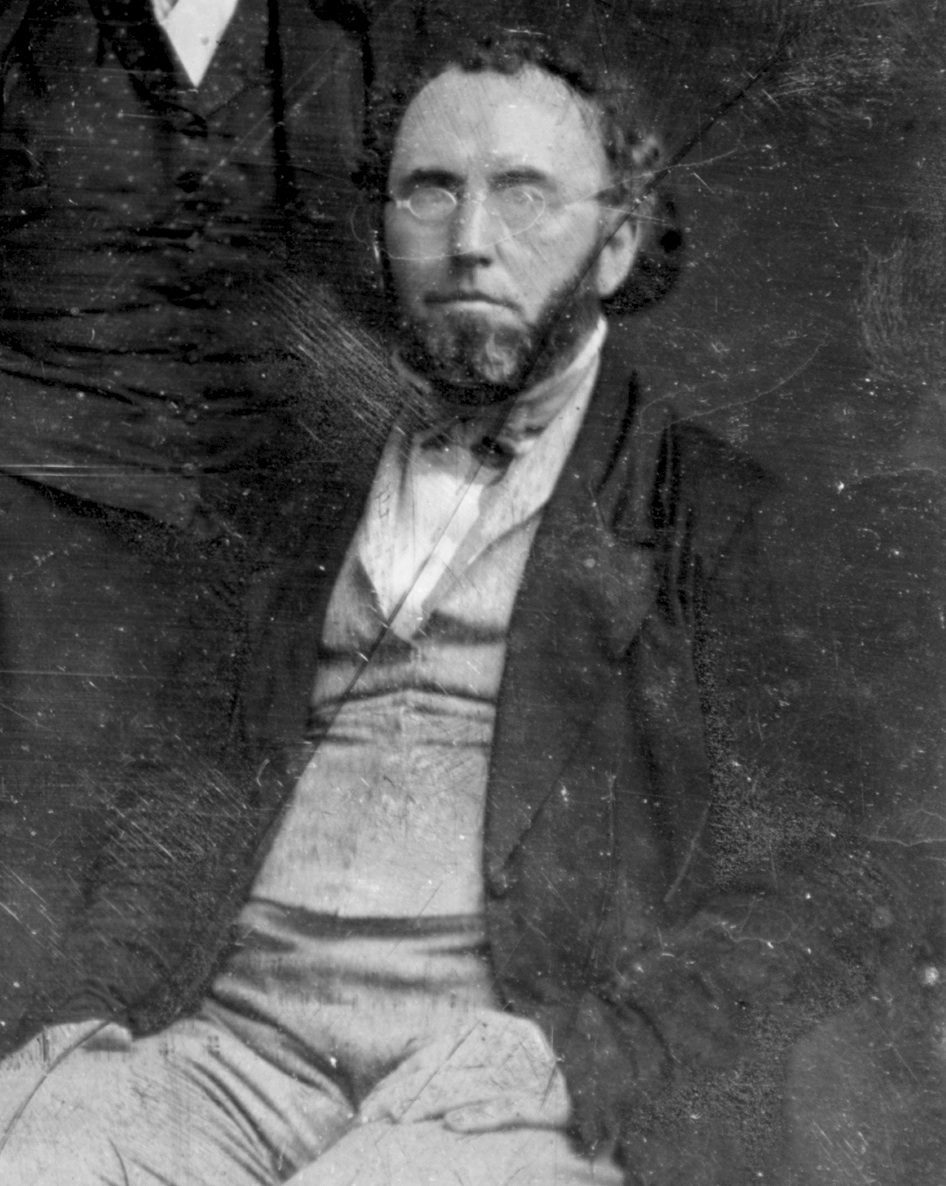

This classic photograph of Ripley, taken by Mathew Brady, is dated somewhere from 1849 to 1860. A brief article about the original promise of Brook Farm from the February 1, 1899 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“‘The Brook Farm Experiment’ was the subject of a lecture given before the Long Island Historical Society last night. The lecturer was Mrs. Julia Ward Howe. The hall of the society, on Pierrepont and Clinton Streets, was so crowded that many stood in the aisles during the whole discourse.

“A tract of arable land was purchased, Mr. Ripley pledging his library for a part of the necessary payment.”

‘The story of what actually took place at Brook Farm,’ Mrs. Howe said, ‘is soon told. A tract of arable land was purchased, Mr. Ripley pledging his library for a part of the necessary payment. A dwelling house already on the premises was altered and enlarged, and other buildings of cheap construction were added from time to time, as the growth of the association made it necessary. Farming must have begun in 1841, as in 1842 Orestes Bronson writes of the community existing and flourishing. The work of the great family was carefully apportioned, Mr. Ripley taking upon himself some of the heaviest and least pleasant part of it, such as the daily cleaning of the stables. Justice was the ideal of the infant association. Within its domain, all labor was equally esteemed. Brain work should enjoy no preference over hand work, and the hand which guided the pen should be ready when so ordered to guide the plow. At times all the members of the community gathered to wash the dishes, and the male members did their full share. The first object in the administration was naturally the support of life. Every effort was made to improve the land, which made but an ungrateful return for such labor. A practical farmer directed agricultural operations, much of what was produced was consumed on the premises, but milk and vegetables, excellent in their kind, were sent to the market. Mr. Ripley once mentioned to me a Boston conservative who used to say that he didn’t like Ripley’s ideas but he did like his peas.'”