Michael Crichton was a major part of the first wave of very educated Americans weaned on genre entertainments who moved B movies to the A-List and put pulp novels atop the New York Times Bestsellers. All the while, he drew the ire of the science community by putting a spotlight on the Victor Frankenstein side of the laboratory, worrying about the Singularity long before the phrase came into vogue (Westworld), thinking about the value corporations might put on the things inside of us prior to Larry Page’s brain-implant dreams (Coma), and considering the perils of de-extinction (Jurassic Park).

The opening of Michael Weinreb’s terrific Grantland consideration of a bad writer who was also a great writer:

At the heart of nearly every Michael Crichton novel is the simplest of premises: a protagonist in trouble, losing control of his world, facing forces he can no longer contain. It’s not exactly a sophisticated plot device, but while Crichton could be a complex thinker in terms of subject matter and scientific inquiry, especially later in his career, he was also an utterly facile writer as far as sentence structure and characterization go. He wrote page-turners that aspired for dystopic realism, and because of this, he is still a polarizing figure whose literary legacy remains unsettled. He once said that scientists criticized him for co-opting their theories into fiction, and that book critics ripped him for writing bad prose.

But one might also argue that few writers in modern history have married high-concept ideas and base-level entertainment as well as Crichton did. His books are the ultimate union of the geeky and the pulpy. Which is why one of this summer’s surefire blockbusters, Jurassic World, and one of this fall’s signature HBO series, Westworld, are both based on ideas that originated in the mind of a man who died almost seven years ago.

♦♦♦

Start with, say, a handsome doctor lured by a beautiful woman to an island that is actually an experiment in the parameters of human need, run by a shadowy corporation that feeds people a drug that (for reasons unknown) turns their urine a bright and shiny blue. Or start with a vacationing playboy who finds himself trapped at a French villa by a surgeon who wields a scalpel as a weapon, like a James Bond villain. Or start with a heist gone wrong, or a madman wielding nerve gas and threatening to attack the Republican National Convention, or a doctor arrested and thrown in jail on charges of performing an illegal abortion.

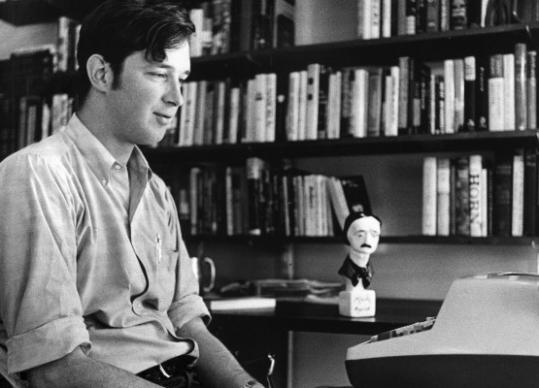

Those are a few of the premises of the nine books Crichton wrote in the late 1960s and early 1970s under varied pseudonyms, when he wasn’t yet a full-time writer and was still playing around with what kind he’d want to be if and/or when he became one. In a way, these novels are the most fascinating experiments of his career, because they’re windows into his thought process, into his own angst about technology and humanity. They’re the demos and B-sides that eventually led to his first best-selling book, 1969’s The Andromeda Strain, about a microorganism run amok. And The Andromeda Strain eventually led to 1990’sJurassic Park, the story of the dinosaurs run amok, the story that turned Crichton into one of the most famous writers on the planet.•