Malcolm Gladwell has a great many talents, but analyzing comedy and satire is apparently not among them. Unfortunately, he held forth on these topics in a recent conversation with economist Tyler Cowen.

The writer once derided satire for not being significant enough to prevent the rise of Nazism, failing to acknowledge that diplomacy, protest, church and media also failed to thwart this mass tragedy. All those institutions and activities have great value, even if they were depressingly unable to avert this particular horror.

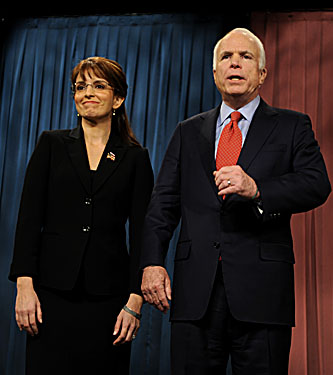

Speaking to Cowen, Gladwell forwards the bizarre theory that Tine Fey’s impersonation of Sarah Palin was great for the comedian’s career but made the politician “more acceptable and likable.” This is an absurd contention. If Katie Couric’s interview with Palin was a mortal wound, Fey’s imitation was the coup de grâce.

Gladwell’s judgment that the impersonation stemmed from Fey’s self-interest is peculiar. Certainly he writes his articles and books to improve his career, and he also does corporate speaking engagements, a very dicey move for a journalist, which I don’t believe Fey does. (Perhaps Gladwell donates all this money to charity, but it remains a potential conflict of interest.)

In the direct aftermath of the Presidential election, when New Yorker EIC David Remnick appeared on TV to warn against the normalization of Trump, he commented that although he believed Hillary Clinton would have been a great President, he thought it was wrong that she accepted huge fees for speaking engagements from investment banks. He probably should hold his staff to the same standard.

Gladwell’s criticism of Alec Baldwin is almost is as wrong-minded. SNL certainly deserves brickbats for allowing the Simon Cowell-ish strongman to host the show during his disgracefully racist campaign, but Baldwin’s characterization isn’t a superficial performance Gladwell describes. Well, at least it’s clear to him that Melissa McCarthy’s Sean Spicer impersonation is greatness.

As for Cowen’s question to Gladwell about Baldwin’s Trump–Is it not sufficiently negative?–he should be asking himself that same query in response to his tepid comments about Peter Thiel, a former interview subject who aggressively enabled a sociopath into the White House. This Administration isn’t merely “flawed” as the economist labeled it in a recent Ask Me Anything. It’s utterly shameful and highly dangerous.

An excerpt:

On Tina Fey, Melisa McCarthy, and good satire

COWEN: It’s been said that satire sometimes reaffirms power, while poetry affirms only its own power. You have a podcast where you express a worry that Tina Fey, by mimicking and satirizing Sarah Palin, actually made her more acceptable and more likeable in doing so. So fast-forward to the current moment: we have Saturday Night Live.

[laughter]

COWEN: Alec Baldwin and Donald Trump. Is that useful satire? Is it not sufficiently negative? Should we be deploying poetry or is that the effective medium for social commentary?

GLADWELL: Well, I don’t like the Alec Baldwin Donald Trump, I don’t think, actually, if you compare it to the Sean Spicer . . .

[laughter]

GLADWELL: It’s not as good, and it’s not as good because the truly effective satirical impersonation is one that finds something essential about the character and magnifies it, something buried that you wouldn’t ordinarily have seen or have glimpsed in that person.

With the Spicer impersonation, why that’s so brilliant is, it draws out his anger. He’s angry at being put in this impossible position. That is the essence of that character. So how does a person respond to this, it’s almost an absurd position he’s in. And he has this kind of — it’s not sublimated — it’s there, this rage. In every one of his utterances is, “I can’t fucking believe that I am in this . . .”

[laughter]

GLADWELL: And so that Saturday Night Live impersonation gets beautifully at that thing, it satirizes that. I’ve forgotten the name of the woman who does it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Melissa McCarthy.

GLADWELL: Yes, when Melissa McCarthy, when she picks up the podium . . .

[laughter]

GLADWELL: That’s an absurd illustration of that fundamental point. But the Alec Baldwin Trump doesn’t get at something essential about Trump. It simply takes his mannerisms and exaggerates them slightly. But he hasn’t mined Trump. There are many directions you can go with Trump, the extraordinary insecurity of the man. Like I said, there are many things you could pluck out, but that for one, the idea of doing an impersonation where you really thought deeply about what it would mean in a comic way to represent this man’s almost tragic level of insecurity. Alec Baldwin is not . . . he’s a little too glib . . .

That’s the problem with Saturday Night Live, the larger problem — I was trying to get at it in that podcast episode on satire — the problem with doing satire through the vehicle of a show like Saturday Night Live is, they’re not incentivized to do that kind of deep thinking. The Melissa McCarthy thing is an exception; it’s not the rule.

Really what they’re incentivized to do is, for the actor — who is in many cases as famous or more famous than the person they are impersonating — the actor is using the character to further their own ends. Tina Fey is infinitely more popular, more accomplished, more whatever than Sarah Palin will ever be. And so she’s using Sarah Palin to further her own ends. That’s backwards. She’s not inhabiting the character of Sarah Palin in order to make a point about Sarah Palin, she is inhabiting Sarah Palin in order to make a point about Tina Fey.

I feel, so long as satire is done by a television show which has such a lofty position in the cultural hierarchy, it’s always going to be the case that that’s what’s going to drive their impersonations. They’re always going to be sitting on their hands. Remember they’re making fun of Trump six months after they had him on the show, right? After they were complicit in his rise, and after Jimmy Fallon ruffled his hair on camera. Maybe that’s fine. My point is you can’t be an effective satirist if you are so deeply complicit in the object of your satire.•