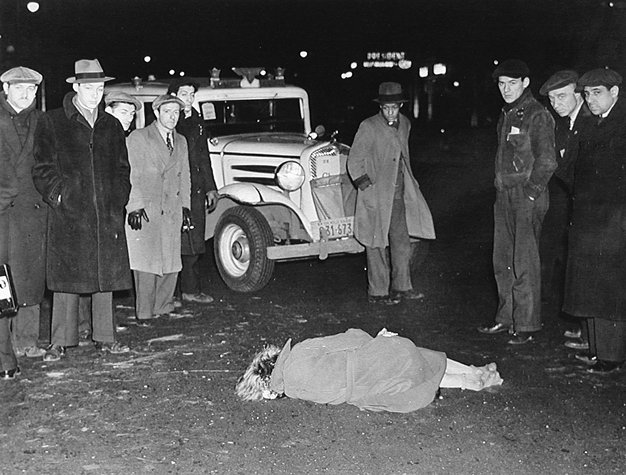

Far fewer American children are playing tackle football in recent years, which might seem a very sane reaction to knowledge about brain injuries caused by the sport, but, in fact, participation in all youth athletics around the country is off by surprising numbers. Where have all the children gone?

Most of them have their heads inside a different type of cloud, the information kind. It’s certainly a life lived more virtually by everyone, but children today are on the front lines of an indoors revolution, Huck Finn now a hologram, and it’s almost strange when you encounter them playing in the streets. In this new arrangement, something’s gained and something’s lost.

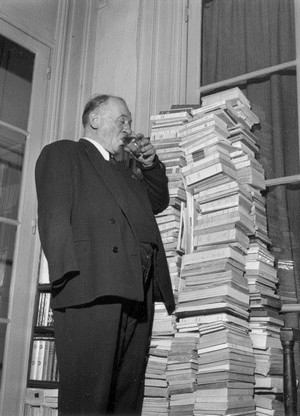

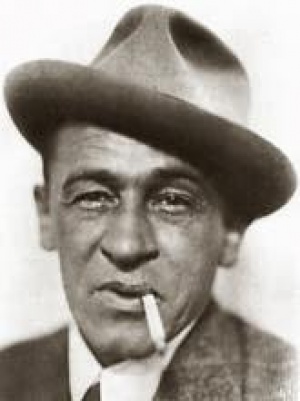

In Andrew Holter’s Paris Review Q&A with Luc Sante, the great writer speaks to this point while discussing his latest book about low life, The Other Paris. The opening:

Question:

Flaneurie is a huge part of The Other Paris—you call the flaneur the “exemplar of this book.” Since flaneurs have been the truest historians of Paris, did you find the act of walking at all important to your research? For as much consideration as you give to the social consequences of the built environment, it seems like a dérive or two might go a long way toward finding the essence of Paris from “the accumulated mulch of the city itself,” to borrow a phrase from Low Life.

Luc Sante:

When I wasn’t at the movies, I was walking. I walked all over the city, repeatedly—I kept journals of my walks, which are actually just lists of the sequences of streets. Even though the city isn’t as interesting as it once was—modern construction and commercial real-estate practices have wiped out so much of the old eccentricity—there are still hidden corners and ornery survivals, and of course the topography is such a determinant. New York City is more or less flat and what isn’t was mostly leveled long ago, so it’s missing that aspect of accommodation to hills and valleys and plateaux, not to mention the laying out of streets on a human scale long before urban planning scaled things to the demands of machines.

Question:

You describe the “intimacy” of cities up until a century ago, even cities the size of Paris, when by default a person’s neighborhood was fundamental to every part of her life, before the phenomenon of commuting and, most crucial of all, “where the absence of voice- and image-bearing devices in the home caused people to spend much more of their time on the street.” Does it distress you that cities have lost that intimacy? You don’t have much patience for nostalgia.

Luc Sante:

I do regret the passing of that intimacy. It was chipped away in increments, by cars, television, chain stores, fear—parental fears of children’s autonomy, “fear of crime,” et cetera—commercial and residential zoning, highway construction, urban renewal, escalating rents, the takeover by corporations of almost all the formerly owner-operated small businesses—groceries, drugstores, coffee shops, stationers, haberdashers, even bodegas. The last bastions of strictly neighborhood commerce are being rapidly decimated by chains these days. And then personal computers, which definitively drove people indoors. The single most jarring of all these changes for me, because so sudden and so absolute after millennia, is the disappearance of children playing in the streets—but then again that’s not confined to cities. I can’t imagine childhood without having the freedom to roam whatever town you’re in.•