Marjoe Gortner was a California-born charismatic child preacher with an overflowing collection plate who grew out of religion and revealed secrets about evangelistic crowd manipulation. Excerpts from two 1970s People articles by Lois Armstrong about Marjoe’s life after he threw off the cloak and pulled back the curtain.

____________________________

From 1976’s “Ex-Kid Gospeler Marjoe Is Hollywood’s New Gun for Hire“:

“It seems fitting that the movie Food of the Gods should star Marjoe Gortner, once a child preacher on the revivalist circuit. As a sermonizer he dwelt on the terrors of hellfire. In Food he is still dealing in fear, but considerably diluted—it’s just a cheapjack monster film. Born again, Marjoe no longer makes his jack in the pulpit. He put his evangelistic soul on ice four years ago with Marjoe, the Oscar-winning documentary that detailed how he preached his first sermon at 4 and by 12 had fleeced his flock of an estimated $3 million.

But at 32, the show goes on for Marjoe. In his view, he’s just shifted his stage from sweaty tents in Appalachia to sweaty sound stages in Hollywood. ‘My whole religious show was just live theater,’ he reflects. To be sure, nowadays he collects not only cash on his plate but starlets. Yet, if anything, Gortner feels purer at heart. It was ‘dangerous,’ he says, ‘telling people they were going to burn in hell.’

At the same time, he isn’t conscience-stricken about his original act. ‘I didn’t feel like a con man,’ he says, ‘because those people were getting a very good show for their money, and I worked very hard.’ When he had the faithful rolling in the aisles, he claims, it was like primal therapy. ‘Those people have more emotions bottled up,’ he says. ‘They lead very uptight lives. For that moment on the floor, they’re in ecstasy.’ So good was young Marjoe, in fact, that in the early 1950s Warner Bros, dangled a deal which was rejected, he concludes, because ‘religion was more lucrative than movies.’

Now that he has made it to the big screen, it seems strange that Gortner is expending his magic on drive-in dreadfuls like Food, a current shoot-’em-up, Bobby Joe and the Outlaws, and the recently completed Viva Knievel, in which Marjoe plays Evel’s lago-like sidekick. Gortner’s response is that he is merely serving his old constituency once more. For example? ‘The guy who works in a Delco factory at a job he hates,’ Marjoe explains, ‘with a wife as fat as hell and a bunch of kids. He’s got to have his fantasies. The people who are going to those movies are the same type who came to the revival meetings, and for the same reason. That’s where they get their entertainment, like other people go to the ballet or a Bob Dylan concert. You can’t blame them for never having been exposed to another culture.’

In his own life Marjoe has embraced that fantasy culture: he lives with a svelte ex-Playmate, tools around in a Porsche or on a hot motorcycle and collects expensive guns and exquisite American Indian jewelry. Without guilt. ‘I came to a basic philosophy,’ he says. ‘I believe in myself. The trouble with most religions is they tell you how to like yourself through God or a guru. It’s harder to deal just with yourself and much more rewarding—you don’t have to report in.’

That wasn’t always true for him.”

____________________________

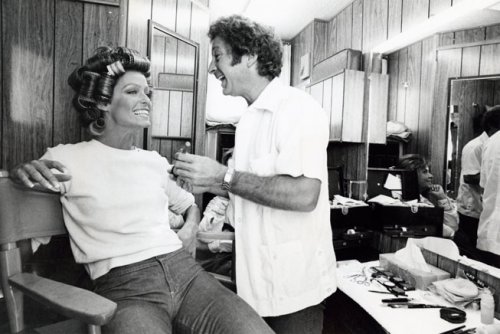

From 1978’s “In Texas, Marjoe Gortner Wraps His First Film and His Second Wife, Candy Clark“:

“They had been dating off and on since last October, Marjoe’s companion of nearly two years, model Lynnda Kimball, having recently moved out. The relationship picked up at Christmas and then he cast the actress in When You Comin’ Back, Red Ryder? A successful off-Broadway play, it is Gortner’s first film-producing effort.

Clark admits to having had a mild crush on her new husband since 1972, when she saw the documentary Marjoe. One night she and a friend, cruising near a Malibu drugstore, spotted him in a purple Rolls-Royce with a license plate that read ‘GREED.’

‘We screamed and yelled and waved,’ she recalls. ‘He waved back and drove off real fast. That probably happened to him every day.’ By then Gortner’s attention had shifted from souls to bodies, especially the voluptuous ones he bumped into at pal Hugh Hefner’s mansion. Three years later he and Clark met at an L.A. restaurant, had an interesting conversation but saw each other only in passing for the next two years. Then one night last July he encountered Candy again in the same restaurant and asked for her phone number.

‘We just gradually grew really close, closer than I’d ever gotten to any other girl,’ he says. ‘Candy’s extremely bright, brighter than this town thinks. She knows how to handle people, and I respect that, possessing those qualities myself.’

Marjoe’s ability to handle—some would say manipulate—people dates back to his 15 years touring the Bible Belt. He was 12 when his dad, the Rev. Vernon Gortner, left home, leaving unaccounted for the $3 million Marjoe’s evangelism had reaped. At 16, Marjoe married and became the father of a daughter, Gigi, now 17. That marriage floundered in the ’60s; so did Marjoe. Then in 1971 he edged into showbiz, playing himself in his screen autobiography before landing the lead in a TV movie, The Gun and the Pulpit, followed by a string of B film roles and TV guest shots.”

____________________________

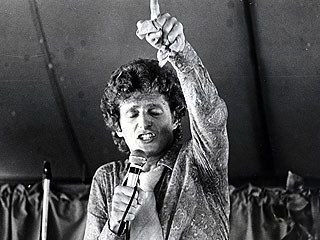

Marjoe counts the money in 1972: