According to the Economist, the narrative of Donald Trump as avenging agent of white working-class Americans left behind by globalization and technology is a seriously overstated myth. The great majority of his supporters, the magazine reports, are doing quite well. My best guess is the well-to-do ones are likely drawn to the hideous hotelier by Identity Politics or racial bias.

In a Newsweek piece, “Trump Revolution Rooted in Resentment of Technology,” Kevin Maney relies on other reports that conversely name a lack of college degree the surest indicator of a Trump follower. The columnist argues that our economy is currently one of Atoms vs. Bits, which means a battle between a declining industrial sector and an ascendant information one. The Atoms, Maney writes, are the truckers, factory workers and other laborers raging against the dying of the light.His theory is an oversimplification as any broadly drawn one is, but it’s hard to deny the societal transformation we’re now experiencing.

Which idea about Team Trump is more correct? Both are probably true enough to be troubling in their own ways, as the rise of the current hate-filled nationalism knows many parents.

Maney’s opening:

We’ve got two Americas now: Atoms America and Bits America.

People used to worry about a digital divide. Well, that’s now looking more like the border between North Korea and South Korea—tense and bristling with pointed missiles, one nervous misunderstanding away from mayhem. This new dynamic is evident in everything from the transgender bathroom laws in the South to proposals from Silicon Valley to institute basic income for all the people technology is going to throw out of work.

And while we’re at it, let’s include the 2016 presidential election, which is really all about Atoms vs. Bits.

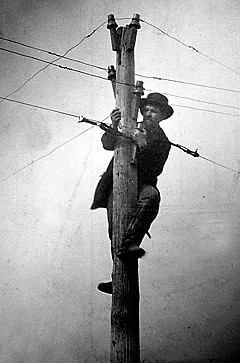

Twenty years ago, Nicholas Negroponte, then head of the MIT Media Lab, wrote about the changing relationship between atoms and bits in his book Being Digital. Atoms make up physical stuff. Bits are digital. As Negroponte presciently pointed out, atoms represent the old economy of manufacturing and trucks and retail stores and, as it turns out, a lot of middle-class work. Bits drive the new economy—which today includes mobile apps, social networks, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, 3-D printing and other technologies that are eating the old economy.

Atoms America is getting poorer and angrier. Bits America pretty much rules the global economy and churns out billionaires.

Atoms America wants to “make America great again” because reclaiming the past seems a hell of a lot better than whatever the future holds. Bits America patronizingly believes that the Atoms people would be fine, at least in the short run, if they would only take some Khan Academy courses and learn to code.•