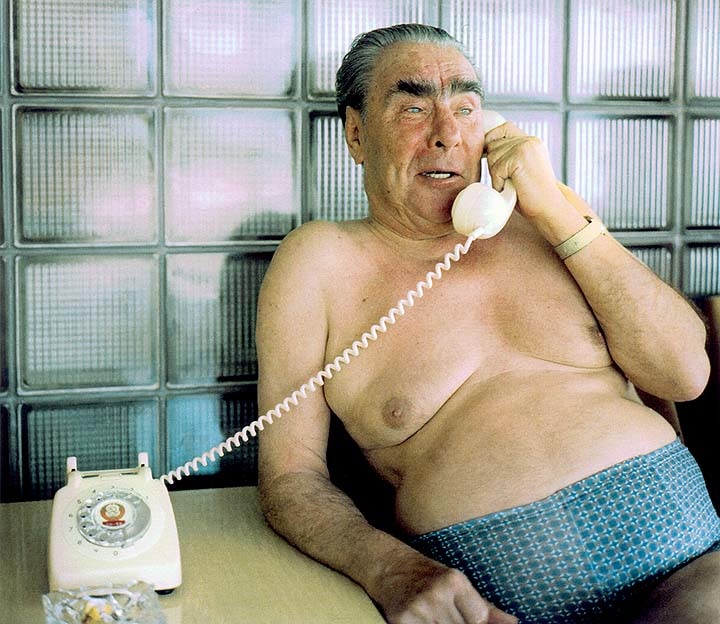

The assassination of Boris Nemtsov, who could almost, if not quite, pass for noble in the confusing welter of modern Russia, was a clap of thunder in the night. By sunrise, the murder made just as little sense. Was he a victim of the authoritarian state or those who opposed its power and viewed him as a useful sacrifice? Either way, his blood flows toward the Kremlin, and not just because of his proximity to the palace when gunned down. From Keith Gessen at the London Review of Books:

For years now there has been speculation about a ‘party of war’, which periodically stages provocations in order to push the president into decisive action. The party of war was said to have manoeuvred Yeltsin into Chechnya and, more conspiratorially still, to have blown up the apartment buildings in Moscow in 1999 to push Putin into Chechnya in his turn. The party of war may also have sent Igor Strelkov and his merry band of murderers into eastern Ukraine last spring, to turn an inchoate set of local protests into the beginnings of a civil war. But does the party of war actually exist? We’re unlikely ever to know, even after all the archives have been opened and all the email accounts hacked. It is, however, a useful concept, even if its only function is to describe one part of Putin’s mind that’s in dialogue or competition with another. It would explain why Putin sometimes goes forward and sometimes steps back. And it gives at least a small space for hope, since if there’s a party of war there is also, presumably, a party of peace, and it might just win.

I always thought that Nemtsov would make it, that he would be shielded from the vengeance of the system in part because he was Nemtsov. He had a PhD in physics, but he wasn’t a serious thinker, nor did he pretend to be one. You could never tell if he was speaking out because he believed what he was saying or because he couldn’t stand being ignored. Or if he kept getting arrested at opposition rallies because he considered it an act of conscience or because he liked getting his picture taken (sometimes, when they arrested him, the police tore his shirt, and you could get an extra glimpse of his tan). Did he hate Putin because of what he’d done to the country, or because he felt cheated out of his birthright by their shared mercurial surrogate father, Boris Yeltsin? He was a narcissist, and there was his way with young women. On the last night of his life, he went with his girlfriend, a Ukrainian model called Anna Duritskaya, to a nice restaurant in the upscale mall just across Red Square from the Kremlin. Then they walked in the rain across the bridge towards his apartment.

Who knows why people do the things they do? Who knows why Nemtsov kept fighting for some kind of change in a country to which he himself had brought a lot of pain? And neither do we know exactly why they killed him. But it’s clear that it wasn’t for his human flaws, or for his contribution to the economic catastrophe of the 1990s. He was killed for his opposition to the war. Since the start, critics have been warning that the war in Ukraine would eventually come home to Moscow. No matter who pulled the trigger on the bridge, it has.•