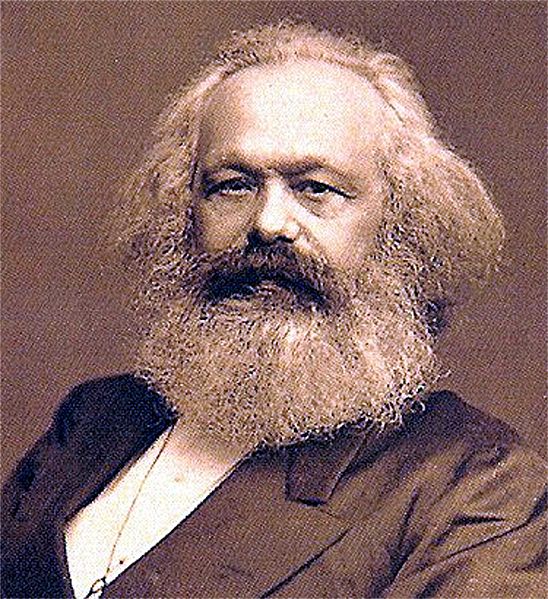

From a 1996 Tom Wolfe essay, a pithy explanation about how Freudianism and Marxism cratered and neuroscience became ascendant:

From a 1996 Tom Wolfe essay, a pithy explanation about how Freudianism and Marxism cratered and neuroscience became ascendant:

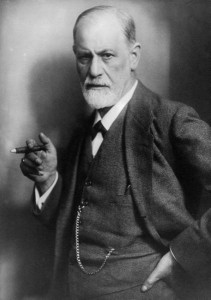

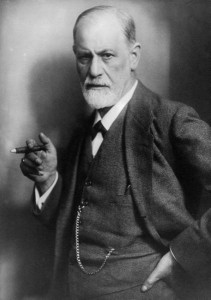

“The demise of Freudianism can be summed up in a single word: lithium. In 1949 an Australian psychiatrist, John Cade, gave five days of lithium therapy—for entirely the wrong reasons—to a fifty–one–year–old mental patient who was so manic–depressive, so hyperactive, unintelligible, and uncontrollable, he had been kept locked up in asylums for twenty years. By the sixth day, thanks to the lithium buildup in his blood, he was a normal human being. Three months later he was released and lived happily ever after in his own home. This was a man who had been locked up and subjected to two decades of Freudian logorrhea to no avail whatsoever. Over the next twenty years antidepressant and tranquilizing drugs completely replaced Freudian talk–talk as treatment for serious mental disturbances. By the mid–1980s, neuroscientists looked upon Freudian psychiatry as a quaint relic based largely upon superstition (such as dream analysis — dream analysis!), like phrenology or mesmerism. In fact, among neuroscientists, phrenology now has a higher reputation than Freudian psychiatry, since phrenology was in a certain crude way a precursor of electroencephalography. Freudian psychiatrists are now regarded as old crocks with sham medical degrees, as ears with wire hairs sprouting out of them that people with more money than sense can hire to talk into.

Marxism was finished off even more suddenly—in a single year, 1973—with the smuggling out of the Soviet Union and the publication in France of the first of the three volumes of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. Other writers, notably the British historian Robert Conquest, had already exposed the Soviet Union’s vast network of concentration camps, but their work was based largely on the testimony of refugees, and refugees were routinely discounted as biased and bitter observers. Solzhenitsyn, on the other hand, was a Soviet citizen, still living on Soviet soil, a zek himself for eleven years, zek being Russian slang for concentration camp prisoner. His credibility had been vouched for by none other than Nikita Khrushchev, who in 1962 had permitted the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s novella of the gulag, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, as a means of cutting down to size the daunting shadow of his predecessor Stalin. “Yes,” Khrushchev had said in effect, “what this man Solzhenitsyn has to say is true. Such were Stalin’s crimes.” Solzhenitsyn’s brief fictional description of the Soviet slave labor system was damaging enough. But The Gulag Archipelago, a two–thousand–page, densely detailed, nonfiction account of the Soviet Communist Party’s systematic extermination of its enemies, real and imagined, of its own countrymen, by the tens of millions through an enormous, methodical, bureaucratically controlled “human sewage disposal system,” as Solzhenitsyn called it— The Gulag Archipelago was devastating. After all, this was a century in which there was no longer any possible ideological detour around the concentration camp. Among European intellectuals, even French intellectuals, Marxism collapsed as a spiritual force immediately. Ironically, it survived longer in the United States before suffering a final, merciful coup de grace on November 9, 1989, with the breaching of the Berlin Wall, which signaled in an unmistakable fashion what a debacle the Soviets’ seventy–two–year field experiment in socialism had been. (Marxism still hangs on, barely, acrobatically, in American universities in a Mannerist form known as Deconstruction, a literary doctrine that depicts language itself as an insidious tool used by The Powers That Be to deceive the proles and peasants.)

Freudianism and Marxism—and with them, the entire belief in social conditioning—were demolished so swiftly, so suddenly, that neuroscience has surged in, as if into an intellectual vacuum. Nor do you have to be a scientist to detect the rush.” (Thanks to The Electric Typewriter.)

More Tom Wolfe posts: