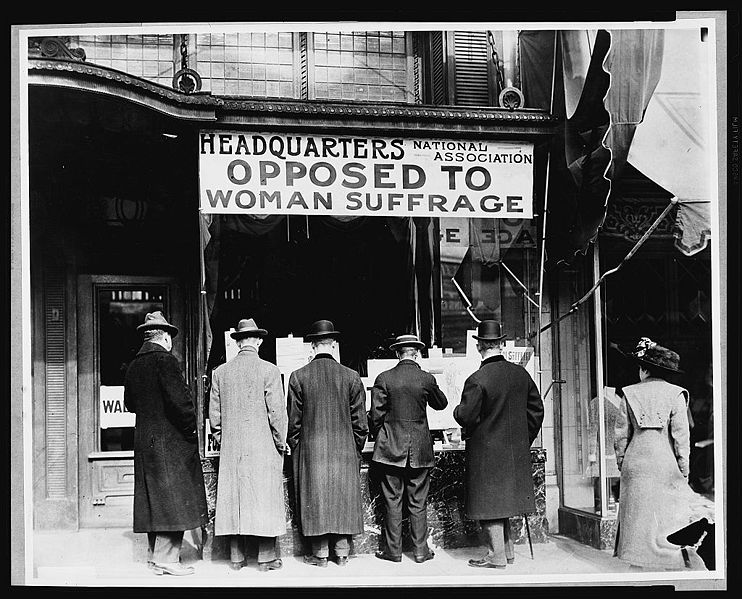

The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, first located in New York and then D.C., was founded by Josephine Dodge. It disbanded in 1920 after the Nineteenth Amendment was passed.

According to a 1902 article in the New York Times, Josephine Dodge (Daskam Bacon) didn’t exactly make a positive impression at a meeting of the Pilgrim Mothers’ Society. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had died just before this meeting took place, founded the Pilgrims, which was decidedly pro-Suffrage. But when Dodge spoke to the group, she really pissed in the punch bowl.

Dodge didn’t seem a likely opponent to the cause. She wrote books with female protagonists and was vital in the development of the Girl Scouts. But she believed that women voting would somehow distract them from doing work in their communities.

Nine years after this speech, Dodge formed the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, which was aimed at keeping the ballot out of women’s hands. Thankfully, she lost that battle when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920. An excerpt from the Times article:

“Miss Josephine Dodge Daskam, the author, rather astonished the members of the Pilgrim Mothers’ Society yesterday afternoon when she expressed her views on ‘The Girls of the Future.’ The women who hold membership in the society, after a dinner in the Astor Gallery of the Waldorf-Astoria, had been listening to responses to toasts on women in business, in law, in medicine, and at the ballot box when Miss Daskam spoke.

‘The young girl of the future,’ she said, ‘I hope may find no greater responsibilities, no wider paths, no greater difficulties than the girl of the present has. Many women who are most valiantly anxious to gain their rights have always forgotten one thing–that the party of the first part, our brothers, are to-day where they were in the beginning; they have always the same advantages, the same responsibilities, the same difficulties, and, fortunately, they have the training to meet them. The girl has all of these things–and 753 extra tasks. And her back is no stronger and her shoulders are just as small as they ever were. I don not think there is much difference between the girl of to-day and Eve.

‘The girl of the future will be definitely obliged to choose between her ever-present privileges and her rights. And, if anybody were to ask me, I would advise her to hang on to her privileges and let her rights go.’

The silence that followed that remark was relieved by the laughter caused by Miss Daskam’s next remark that ‘if you can’t get your vote, you can always get your voter, and you can influence him in his vote.’

Miss Daskam then proposed what she called a ‘little scheme.’ ‘Let him,’ she said, ‘live and perish in the conviction that he knows and can do many things that you cannot, and always pretend that you never know.’ She said that men wanted to do for women things which they believed women could not do, and were angered when they learned that they could do those things. She said that the man ought to be permitted to keep the bank book, and to decipher for his wife the railroad time table, a thing which, of course, no woman is capable of doing.”