Late to Industrialization, China entered the process knowing what much of the Western world had to learn the hard way in the 1970s: Urbanizing and modernizing an entire nation brings with it tremendous economic growth, but it can’t be sustained by the same methods–or perhaps at all–when the mission is complete. It’s a one-time-only bargain.

A richer nation can’t grow endlessly on the production of cheap exports, so the newly minted superpower is pivoting more to domestic demand, a nuance no doubt lost in the Trump Administration’s ham-handed appreciation of global politics. In “Trump’s Most Chilling Economic Lie,” a Joseph Stiglitz Vanity Fair “Hive” article, the economist highlights the insanity of America engaging in a trade war with China and expecting to emerge the richer. An excerpt:

Trump’s team may be tempted to conclude, naively, that because China exports so much more to the U.S. than the U.S. exports to China, the loss of a huge export market would hurt them more than it would hurt us. This reasoning is too simplistic by half. China’s government has far more control over the country’s economy than our government has over ours; and it is moving from export dependence to a model of growth driven by domestic demand. Any restriction on exports to the U.S. would simply accelerate a process already underway. Moreover, China’s government has the resources (it’s still sitting on some $3 trillion of reserves) and instruments to help any sector that has been shut out—and in this respect, too, China is better placed than the U.S.

China has already shown how it is likely to respond if Trump should launch a trade war. At Davos, President Xi Jinping came out as the great supporter of globalization and the international rule of law—as well China should. China, with its large emerging middle class, is among the big beneficiaries of globalization. Critics have said that China does not always play fair. They complain that as China has grown, it has taken away some of the privileges, some of the tax preferences, that it gave to foreigners in earlier stages of development. They are unhappy, too, that some Chinese firms have learned quickly how to compete—some of them even appropriating ideas from others, just as we appropriated intellectual property from Europe more than a century ago.

It is worth noting that, although large multinationals complain, they are not leaving. And we tend to forget the extensive restrictions we impose on Chinese firms when they seek to invest in the U.S. or buy high-tech products. Indeed, the Chinese frequently point out that if the U.S. lifted those restrictions, America’s trade deficit with China would be smaller.

China’s first response will be to try to find areas of cooperation. They are experts in construction. They know how to build high-speed trains. They might even provide some financing for these projects. Given Trump’s rhetoric, though, I suspect that such cooperation is just a dream.

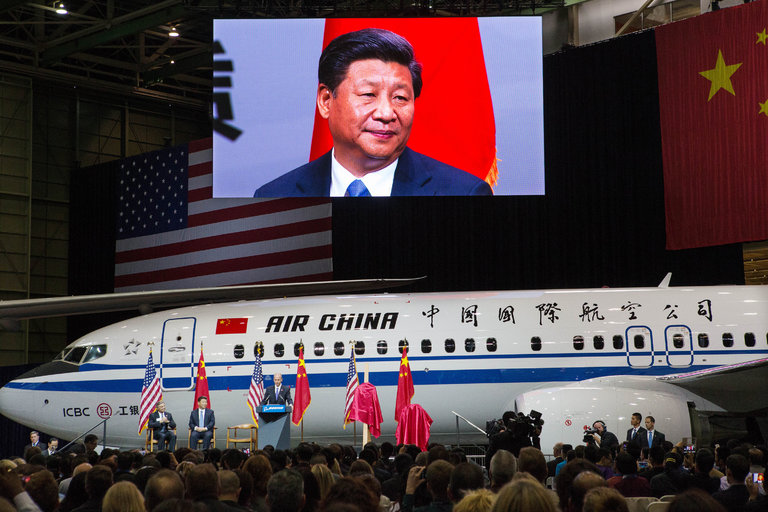

If Trump insists on an adversarial stance, China is likely to respond within the framework of international law even if Trump puts little weight on such agreements—and thus is not likely to retaliate in a naive, tit-for-tat way. But China has made it clear that it will respond. And if history is any guide, it will respond both forcefully and intelligently, hitting us where it hurts economically and politically—where, for instance, cutbacks in purchases by China will lead to more unemployment in congressional districts that are vulnerable, influential, or both. If Boeing’s order book is thin, it might, for instance, cancel its purchases of Boeing planes.•