Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Lessig is crowdfunding in the hopes of financing a run for President not as a protest candidate but as a referendum candidate, one who would resign and cede the office to his Veep after a very brief first act of fixing our troubled political system (campaign finance, gerrymandering, etc.). We certainly need these things to occur, but it almost definitely won’t happen, at least not directly, because of Lessig’s quixotic campaign. Elizabeth Warren was really the only potential candidate who had a chance of undoing at least some of this wrong-mindedness, but she isn’t running.

I’m hopeful that Lessig and other campaigns will make these important issues central in the way the Occupy movement pushed wealth inequality into the mainstream. However, Lessig himself doesn’t believe just making reform one of many major issues will work–it needs to be a candidate’s number one and perhaps only concern. Let’s hope that’s not true, because a person running to reform and resign isn’t likely getting elected. What would make for a spellbinding TED Talk doesn’t necessarily translate into a real-life solution.

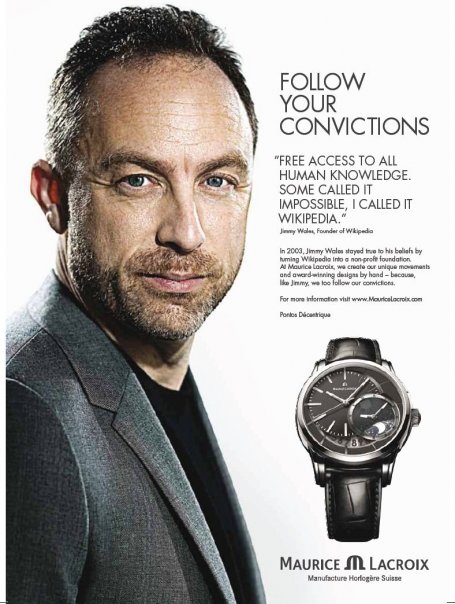

Lessig and his supporter Jimmy Wales (a “foreigner,” as President Trump would call him) just did an AMA at Reddit. A few exchanges follow.

___________________________

Question:

What led you to decide to run yourself instead of remaining an advisor to Sanders’ campaign? Don’t you think that the MOST LIKELY scenario would be that, by some (increasingly likely) miracle, Sanders overtakes Clinton for the nomination? Why can’t Sanders introduce the Citizens Equality Act and do the same things you want to do, but remain president?

Lawrence Lessig:

I became convinced that Sanders has been seduced by the consultants, whose aim (this is why they’re hired) is to elect him rather than run a campaign that might be harder, but would give him the mandate to lead. I believe Bernie can get elected. But if he runs his campaign as he has, it will be Obama v2.0 (not in the substance but in the inability to pass or even propose reform).

___________________________

Question:

Could Elizabeth Warren be your Vice President?

Lawrence Lessig:

Yes, absolutely. Politically, it would make sense for one of us to move out of MA (and that would be me since she’s the senator). That’s because the constitution wouldn’t permit MA to cast its votes for both of us, and so if the election were close, that would risk one of us not making it. But constitutionally, there is no bar (except the rule that forbids a state to vote for two people from that state).

___________________________

Question:

How can we connect issues of campaign finance and voter equality with the day-to-day practical & emotional realities of regular Americans?

Lawrence Lessig:

The pundits think Americans are stupid. I don’t. I think that if you connect the dots, they’ll get it. Start with the issues they care about — health care, social security, student debt, minimum wage, the environment, network neutrality, copyright (ok, a guy can dream) — and show them how EVERY ISSUE is linked to this one issue. Try an obvious metaphor: An alcoholic could be losing his liver, his job, his wife. Those are the worst problems someone can have. But unless you solve the alcoholism, none of those problems is going to be solved.

___________________________

Question:Why did you decide to create the Citizens Equality Act instead of trying to get a Constitutional amendment passed like Wolf PAC is trying to do?

Lawrence Lessig:

Because (1) we need reform NOW (not 3 years from now), (2) a majority in Congress is more likely than 2/ds (to propose), or 3/4ths (to ratify), (3) because changing the way campaigns are funded is something Congress could do tomorrow, and should. An amendment may well be necessary — if the Supreme Court doesn’t fix the superPAC problem it is certainly necessary — but we can’t afford to wait. We need to act through Congress now.

___________________________

Question:

Say you’re elected, and the Citizen Equality Act of 2017 isn’t passed by Congress. Now What?

Lawrence Lessig:

Not an option. With 50 referendum representatives, and a president that doesn’t care about what’s next, it gets passed.

I get the anxiety here. I really do. But here’s the reality: We have a government that doesn’t work. We need the best shot to getting a government that does work. Making “reform” one of 8 issues on a platform is not a plan. It’s a wish.

___________________________

Question:

A healthy democracy requires the enforcement of law. But today, law enforcement officials are able to routinely violate citizen’s legal and Constitutional rights with impugnity.

Do you believe Campaign Zero’s policy proposals (link) are adequate to provide communities adequate means to hold their police departments accountable, safeguard individual’s rights, and eliminate racial bias? Do you believe the adequately safeguard the disabled, the non-neurotypical, and the mentally ill?

If not, what additional policies would you support?

Lawrence Lessig:

Agreed. This ties to the culture of inequality that is America today. We don’t have equal citizens, and that spreads to every aspect of social life. The stupid war on drugs turns police into drill sergeants, and they treat citizens as grunts in boot camp. The only way we change this is to reaffirm the basic equality of citizens, and use that power to undo these idiotic laws.•