I posted a brief Jeremy Bernstein New Yorker piece about Stanley Kubrick that was penned in 1965 during the elongated production of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The following year the same writer turned out a much longer profile for the same magazine about the director and his sci-fi masterpiece. Among many other interesting facts, it mentions that MIT AI legend Marvin Minsky, who’s appeared on this blog many times, was a technical consultant for the film. An excerpt from “How About a Little Game?” (subscription required):

By the time the film appears, early next year, Kubrick estimates that he and [Arthur C.] Clarke will have put in an average of four hours a day, six days a week, on the writing of the script. (This works out to about twenty-four hundred hours of writing for two hours and forty minutes of film.) Even during the actual shooting of the film, Kubrick spends every free moment reworking the scenario. He has an extra office set up in a blue trailer that was once Deborah Kerr’s dressing room, and when shooting is going on, he has it wheeled onto the set, to give him a certain amount of privacy for writing. He frequently gets ideas for dialogue from his actors, and when he likes an idea he puts it in. (Peter Sellers, he says, contributed some wonderful bits of humor for Dr. Strangelove.)

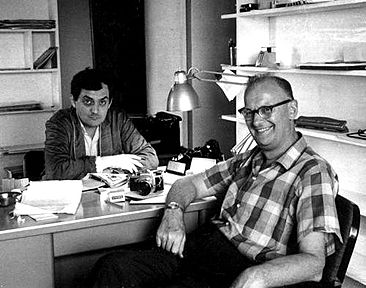

In addition to writing and directing, Kubrick supervises every aspect of his films, from selecting costumes to choosing incidental music. In making 2001, he is, in a sense, trying to second-guess the future. Scientists planning long-range space projects can ignore such questions as what sort of hats rocket-ship hostesses will wear when space travel becomes common (in 2001 the hats have padding in them to cushion any collisions with the ceiling that weightlessness might cause), and what sort of voices computers will have if, as many experts feel is certain, they learn to talk and to respond to voice commands (there is a talking computer in 2001 that arranges for the astronauts’ meals, gives them medical treatments, and even plays chess with them during a long space mission to Jupiter–‘Maybe it ought to sound like Jackie Mason,’ Kubrick once said), and what kind of time will be kept aboard a spaceship (Kubrick chose Eastern Standard, for the convenience of communicating with Washington). In the sort of planning that NASA does, such matters can be dealt with as they come up, but in a movie everything is visible and explicit, and questions like this must be answered in detail. To help him find the answers, Kubrick has assembled around him a group of thirty-five artists and designers, more than twenty-five special effects people, and a staff of scientific advisers. By the time this picture is done, Kubrick figures that he will have consulted with people from a generous sampling of the leading aeronautical companies in the United States and Europe, not to mention innumerable scientific and industrial firms. One consultant, for instance, was Professor Marvin Minsky, of M.I.T., who is a leading authority on artificial intelligence and the construction of automata. (He is now building a robot at M.I.T. that can catch a ball.) Kubrick wanted to learn from him whether any of the things he was planning to have his computers do were likely to be realized by the year 2001; he was pleased to find out that they were.•