Long before Silicon Valley, Victorians gave the future a name, recognizing electricity and, more broadly, technology, as transformative, disruptive and decentralizing. We’re still borrowing from their lexicon and ideas, though we need to be writing the next tomorrow’s narratives today. From “Future Perfect,” Iwan Rhys Morus’ excellent Aeon essay:

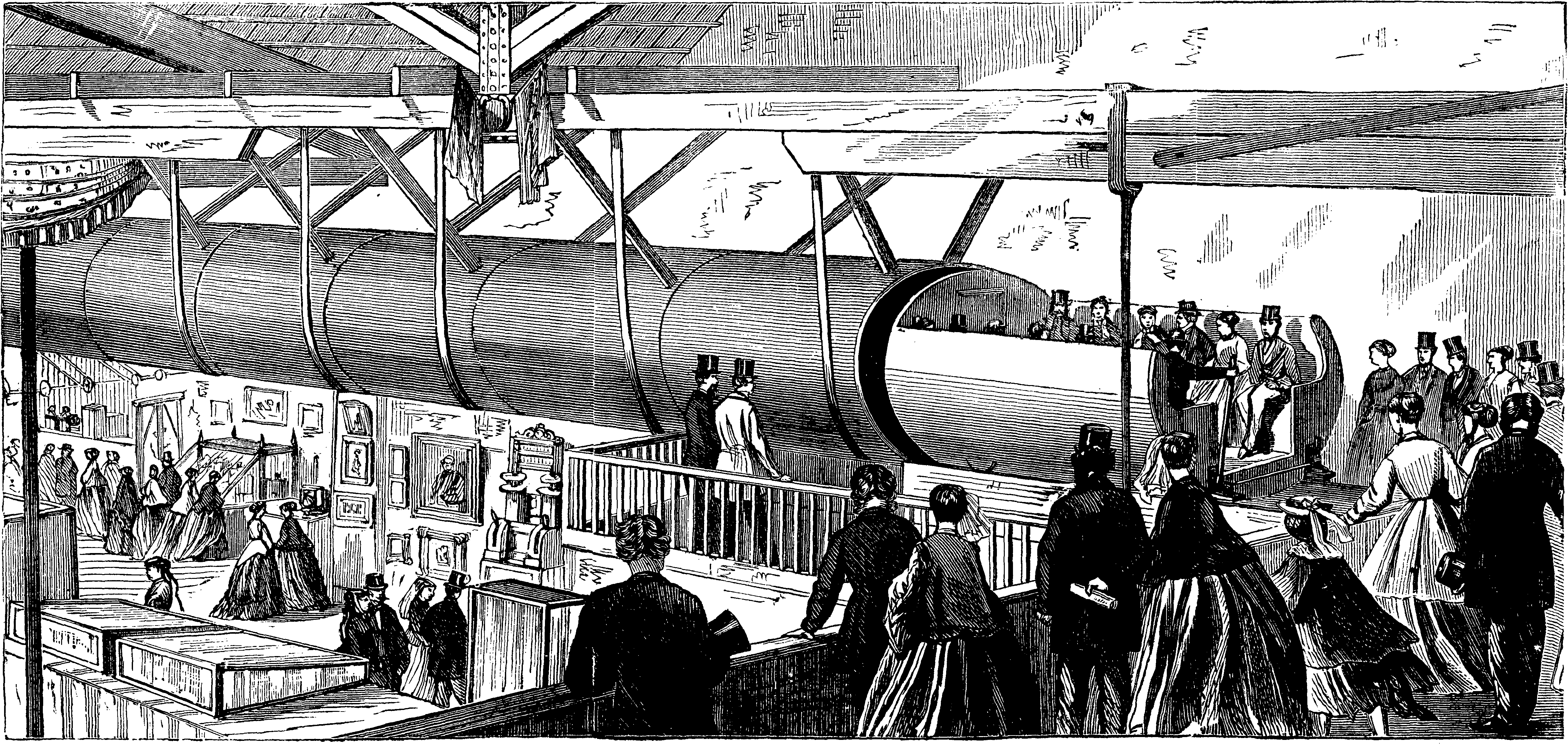

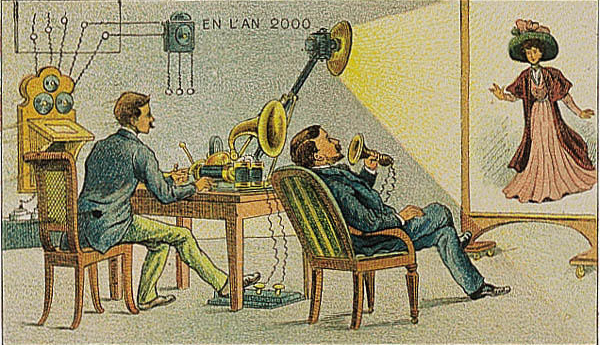

“For the Victorians, the future, as terra incognita, was ripe for exploration (and colonisation). For someone like me – who grew up reading the science fiction of Robert Heinlein and watching Star Trek – this makes looking at how the Victorians imagined us today just as interesting as looking at the way our imagined futures work now. Just as they invented the future, the Victorians also invented the way we continue to talk about the future. Their prophets created stories about the world to come that blended technoscientific fact with fiction. When we listen to Elon Musk describing his hyperloop high-speed transportation system, or his plans to colonise Mars, we’re listening to a view of the future put together according to a Victorian rulebook. Built into this ‘futurism’ is the Victorian discovery that societies and their technologies evolve together: from this perspective, technology just is social progress.

The assumption was plainly shared by everyone around the table when, in November 1889, the Marquess of Salisbury, the Conservative prime minister of Great Britain, stood up at the Institution of Electrical Engineers’ annual dinner to deliver a speech. He set out a blueprint for an electrical future that pictured technological and social transformation hand in hand. He reminded his fellow banqueteers how the telegraph had already changed the world by working on ‘the moral and intellectual nature and action of mankind’. By making global communication immediate, the telegraph had made everyone part of the global power game. It had ‘assembled all mankind upon one great plane, where they can see everything that is done, and hear everything that is said, and judge of every policy that is pursued at the very moment those events take place’. Styling the telegraph as the great leveller was quite common among the Victorians, though it’s particularly interesting to see it echoed by a Tory prime minister.

Salisbury’s electrical future went further than that, though. He argued that the spread of electrical power systems would profoundly transform the way people lived and worked, just as massive urbanisation was the result of steam technology.”