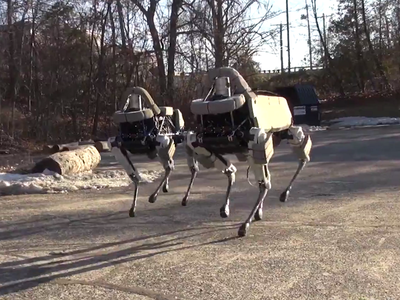

A hammer can be a tool or a weapon depending on how you swing it, and that’s important to remember while we’re being wowed by Boston Dynamics’ new four-legged robot, Spot. Neel V. Patel of Wired noticed something about the viral video showcasing the AI: a moment which is perhaps coincidence or maybe collective behavior, even if it isn’t swarm robotics. An excerpt:

We’ve seen all of this—admittedly amazing—stuff out of BD’s four-legged robots before. But it gets crazier around the 1:20 mark, when a pair of Spots begin trekking up a hill. Spot Number One starts repeatedly colliding into Spot Number Two—and neither loses balance. After a few seconds and a bit of subtle push-and-shove, they straighten out and walk in parallel again, and then turn together once they reach the top of the hill. This is getting creepy, guys—it looks like these robots are exhibiting the same swarm-like behavior that we see in animals.

We checked in with Iain Couzin, a Princeton biologist and expert in the study of collective animal behavior, to get his take on the robots’ seeming hive mind.

We know from Spot’s reaction to that kick that he can dynamically correct his stability—behavior that’s modeled after biological systems. From what Couzin can tell, the robots’ collective movement is an organic outgrowth of that self-correction. When the two Spots collide at the 1:25 mark, they’re both able to recover quickly from the nudge and continue on their route up the hill. “But the collision does result in them tending to align with one another (since each pushes against the other),” Couzin wrote in an email. “That can be an important factor: Simple collisions among individuals can result in collective motion.”

In Couzin’s research on locusts, for example, the insects form plagues that move together by just barely avoiding collisions. “Recently, avoidance has also been shown to allow the humble fruit fly to make effective collective decisions,” he wrote.

It doesn’t look like Spot is programmed to work with his twin brothers and sisters—but that doesn’t matter if their coordination emerges naturally from the physical rules that govern each individual robot. Clearly, bumping into each other isn’t the safest or most efficient way to get your robot army to march in lock step, but it’s a good start.•