“What we dream we become” wrote Henry Miller, offering a curse as much as a promise, wary as he always was of science and technology and America.

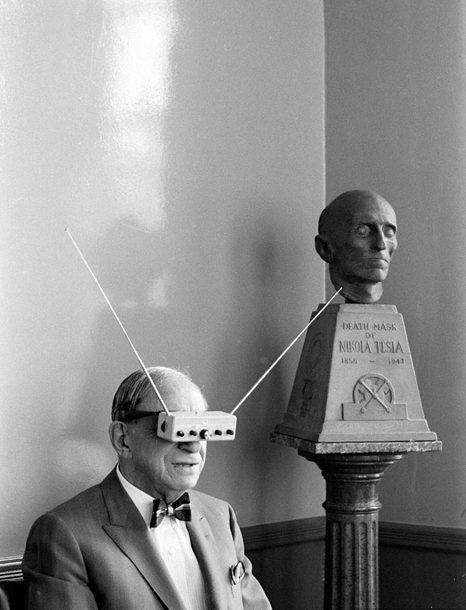

Nobody in the U.S. has ever dreamed more than Hugo Gernsback, immigrant technological tinkerer and peddler of science fiction, and he was sure the most outré visions would come to pass: instant newspapers printed in the home, TV eyeglasses, teleportation, etc. Some of these amazing stories proved to be true and others…perhaps someday? In Gernsback’s view what separated fiction and fact was merely time.

From James Gleick’s wonderful New York Review of Books piece about The Perversity of Things: Hugo Gernsback on Media, Tinkering, and Scientifiction:

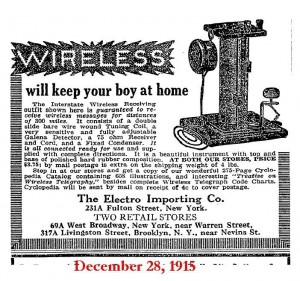

Born Hugo Gernsbacher, the son of a wine merchant in a Luxembourg suburb before electrification, he started tinkering as a child with electric bell-ringers. When he emigrated to New York City at the age of nineteen, in 1904, he carried in his baggage a design for a new kind of electrolytic battery. A year later, styling himself in Yankee fashion “Huck Gernsback,” he published his first article in Scientific American, a design for a new kind of electric interrupter. That same year he started his first business venture, the Electro Importing Company, selling parts and gadgets and a “Telimco” radio set by mail order to a nascent market of hobbyists and soon claiming to be “the largest makers of experimental Wireless material in the world.”

His mail-order catalogue of novelties and vacuum tubes soon morphed into a magazine, printed on the same cheap paper but now titled Modern Electrics. It included articles and editorials, like “The Wireless Joker” (it seems pranksters had fun with the new communications channel) and “Signaling to Mars.” It was hugely successful, and Gernsback was soon a man about town, wearing a silk hat, dining at Delmonico’s and perusing its wine list with a monocle.Public awareness of science and technology was new and in flux. “Technology” was barely a word and still not far removed from magic. “But wireless was magical to Gernsback’s readers,” writes Wythoff, “not because they didn’t understand how the trick worked but because they did.” Gernsback asked his readers to cast their minds back “but 100 years” to the time of Napoleon and consider how far the world has “progressed” in that mere century. “Our entire mode of living has changed with the present progress,” he wrote in the first issue of Amazing Stories “and it is little wonder, therefore, that many fantastic situations—impossible 100 years ago—are brought about today.”

So for Gernsback it was completely natural to publish Science Wonder Stories alongside Electrical Experimenter. He returned again and again to the theme of fact versus fiction—a false dichotomy, as far as he was concerned. Leonardo da Vinci, Jules Verne, and H. G. Wells were inventors and prophets, their fantastic visions giving us our parachutes and submarines and spaceships.•