Here’s a wonderful featurette about Francis Ford Coppola making The Conversation, the 1974 psychological thriller, which moved the disquiet of Antonioni’s Blow-Up into the Watergate era, asked questions about a world where everyone is a spy and spied upon. The surprise 40 years later: Few seem upset about the new order of the techno-society. We haven’t been trapped after all; we’ve logged on and signed up for it. My short essay about the film follows the video.

A product of the Watergate decade, an era when spying and snooping at least gave us pause, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation was made before ubiquitous public security cameras were watching us, phones were tracking us and seemingly everyone was living in public. A lack of privacy has never been as well-regarded as it is today nor have the perils of such actions, which are investigated in this film, been so invisible.

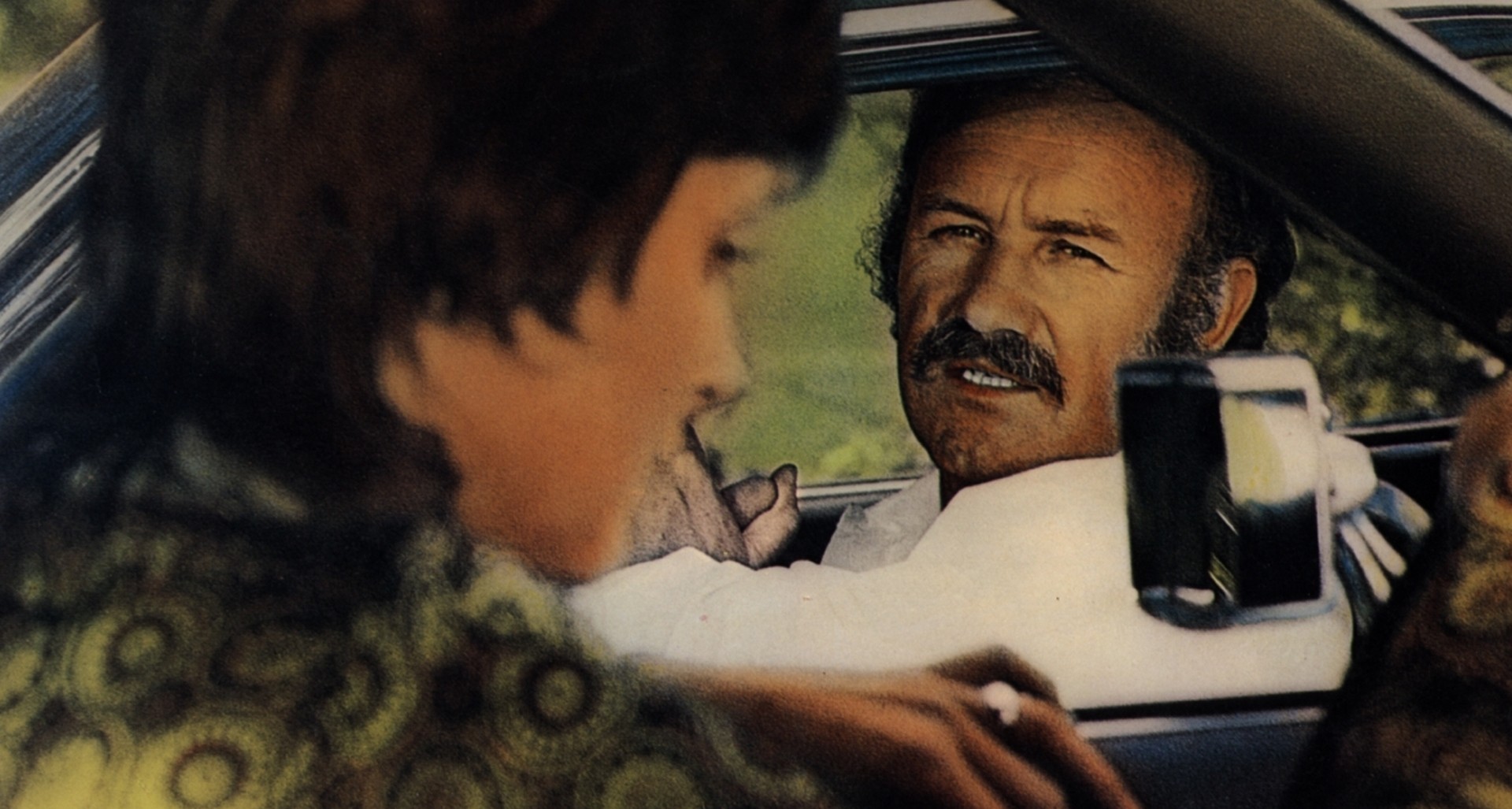

Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) is a jazz loving San Franciscan who earns his living as a surveillance expert, stealthily recording private conversations with an elaborate array of mikes of his own making. Caul is top dog in the trade, and he’s paid handsomely to find answers for his bosses and not ask them any questions. A devout Catholic, the wire tapper has moral issues with his work, especially since information he culled in a past case led to murder. But it’s hard for Caul to stop doing what he’s doing because he’s so damn good at it, something of an artist.

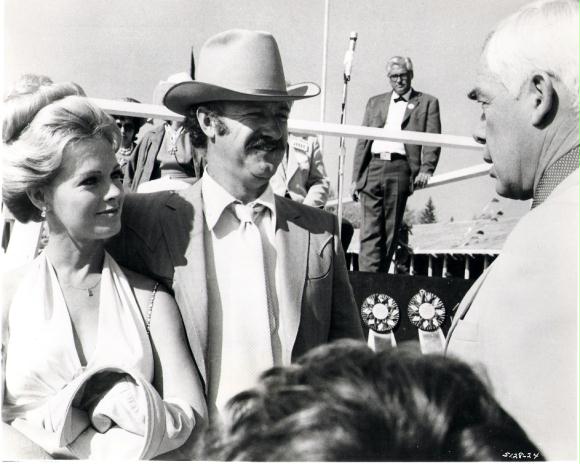

While he may be an artist, Caul is definitely a hypocrite. He keeps everything about himself strictly private, even from his girlfriend (Teri Garr) and point man (John Cazale). He rationalizes he’s doing it for safety reasons, but it’s also in his nature. This delicate balance is thrown off-kilter when Caul believes his latest assignment, in which a wealthy man is paying for info about his young wife, may also lead to murder. Caul can’t head down that road again and a crisis of conscience makes him go rogue. Soon he himself is the target of surveillance, a probing that he can’t withstand.

In the era that saw the downfall of an American President who listened to the tapes of others and erased his own, The Conversation was amazingly relevant, but in some ways it may be even more meaningful in this exhibitionist age, in which we gleefully hand over our privacy to satisfy our egos. As Caul and Nixon learned, and as we may yet, those who press PLAY don’t always get to choose when to press STOP.•