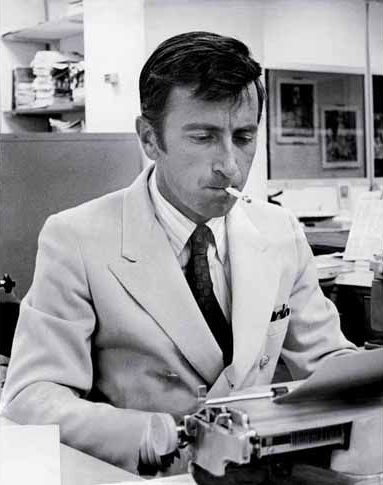

The excerpt from Gay Talese’s The Voyeur’s Motel that unfortunately ran recently in the New Yorker was more than enough for me–way more than enough–and I won’t be investing the time to read the dodgy book. Absent journalistic and personal ethics, the story has been further muddied by revelations of fabrications that basic reportage would have uncovered. Excuses have been made, but the work is stained by the worst excesses of New Journalism, which opened the craft to a wider style, sure, but also made reporting prone to dubious veracity and methods. It’s odd the piece ended up in the New Yorker, which under David Remnick has largely been an impenetrable fortress against such slipshod narratives.

Jack Shafer has read the book so we don’t have to, reviewing it for the New York Times. His opening:

The average reader will greet more with anger than sadness Gay Talese’s disclosure — almost halfway through his book The Voyeur’s Motel — that the detailed sex journal underpinning this zany work of nonfiction can’t be trusted.

Talese — whose use of the tools of fiction to propel factual accounts helped found New Journalism in the 1960s — drops the self-impeaching evidence casually. Calling into doubt the veracity of his book, Talese writes that the suburban Denver motel owner Gerald Foos claims to have started observing and transcribing the private business of his guests in 1966, peering down at them through 6-by-14-inch surveillance grates he installed in the ceilings of a dozen rooms of his 21-unit motel. The problem with the Foos account, Talese adds, is that he didn’t buy Manor House Motel until 1969, meaning that he must have imagined several years of the wild motel bed-sports described in his journal.

Further evidence that the Foos story is cooked: “And there are other dates in his notes and journals that don’t quite scan,” Talese writes, stating that Foos “could sometimes be an inaccurate and unreliable narrator.”

Ordinarily when a journalist discovers profoundly discrediting testimony like this, he utters “Whoa,” itemizes the discrepancies and digs deeper. But not so Talese, who only shrugs at the revelation that his main source has lied to him without detailing the fibs. “I cannot vouch for every detail that he recounts in his manuscript,” he writes.