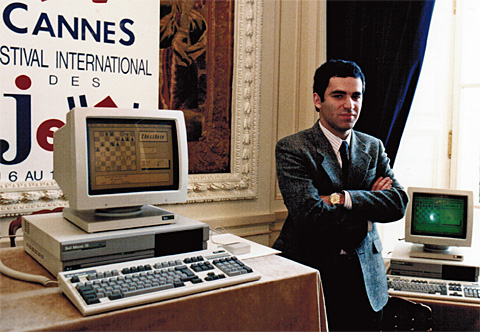

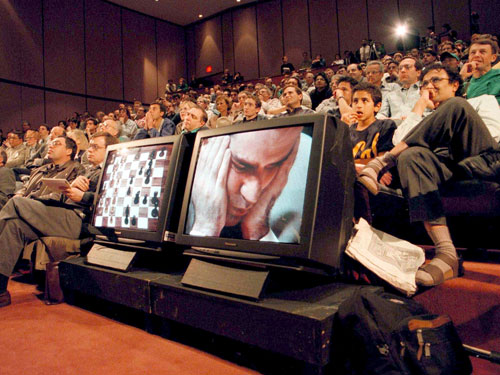

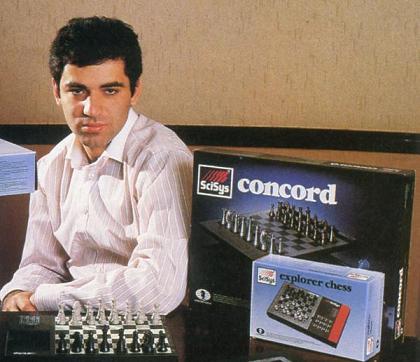

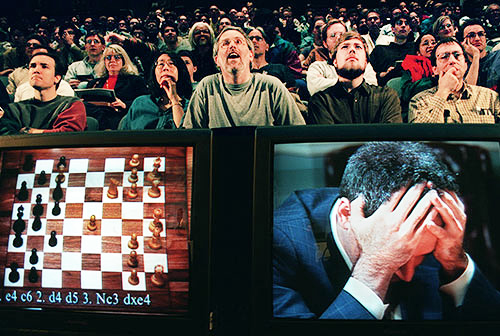

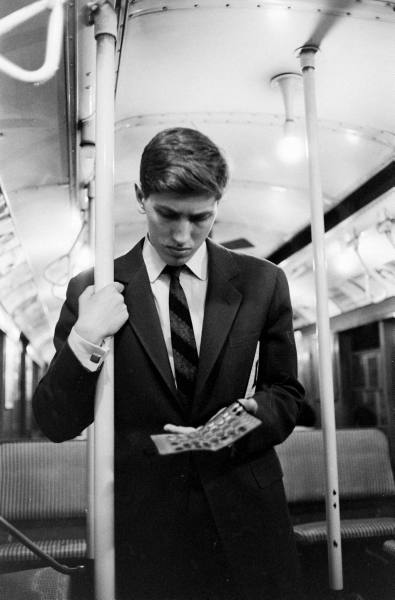

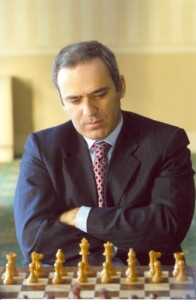

Loved the long centerpiece of Garry Kasparov’s Deep Thinking, in which perhaps the greatest chess champion of all recreates his epic 1996 and 1997 matches with Deep Blue, the IBM program that ultimately toppled him–and by extension, us. The barrage of machinations employed by the computer company are fascinating and worthy of Cold War spooks, which makes this section read like an espionage thriller married to insightful sportswriting.

The rest of the book is an interesting meditation on the intelligent machines that increasingly surround us, consume us, though Kasparov’s argument that we should stop worrying and learn to love the “bomb” doesn’t completely convince because he gives short shrift to the many potential pitfalls.

A few random thoughts.

· · ·

While Steven Levy’s cover line, “The Brain’s Last Stand,” was a great way to sell his Newsweek article that previewed the second match, it also was a simplification of a complex point. There’s no one instant when intelligent machines absolutely surpass us, no Turing Test or ego-deflating checkmate, Watson win or Singularity moment can do the trick. It’s a gradual process. Apollo 11’s success, IBM’s victory and Deep Learning’s mysterious prowess are all part of an eerie landscape in which there is no Main Street. The landmarks are scattered and continually being built.

Kasparov makes this point himself in depicting the titanic contests as great theater and personally taxing but almost completely beside the point. He knew that even if he triumphed in ’97, the machines would soon far surpass their carbon-based competitors. Kasparov might have staved off IBM long enough to avoid being the one to “earn” the John Henry tag, but soon enough the number one player in the world, whoever that may have been, was going down.

· · ·

Early in the volume, on page 47, Kasparov tries to relate to people whose livelihoods, and sometimes communities, have been devastated by technological innovation (in tandem with globalization), arguing that “few people in the world know better than I do what it’s like to have your life’s work threatened by a machine.” Hmm, it would seem that a brilliant, world-famous, fairly well-off guy in his thirties would be fine even if he was shoved aside by AI, but maybe he was truly terrified like those who hope the plant in Ohio doesn’t kick them to the curb.

Later that very same page, however, Kasparov writes: “Nor did I believe the apocalyptic predictions about what might happen if I lost a match to a machine. I was always optimistic about the future of chess in a digital age.” Whew, crisis averted!

The author sees a progression in which for a period of indeterminate length humans and machines collaborate on many forms of work until our silicon sisters take full control of these processes and we move on to other more important matters. That’s probably correct, but it’s not so likely to unfold as neatly off the page, especially since industries can rise and fall far more quickly during a technological boom.

Think how rapidly CDs went from the most successful format in music-business history to being almost worthless when the sounds disappeared into the 0s and 1s. Consider that Blockbuster and Polaroid and Fotomat went under during just the first wave of the Internet. Even if the aggregate job numbers don’t end up diminished, discomfiting displacement may become a permanent feature of life, as we’re all engaged in a never-ending game of musical chairs. That can’t be healthy for a society. From an economic standpoint, you wouldn’t want to be a nation that misses out on the Digital Age, but things could, and probably will, get messy. Some will be seated comfortably and many will fall to the floor.

· · ·

I’m working from memory, but I think Kasparov dedicates about three pages to the thorny problems of surveillance, privacy, hacking, etc. That’s not nearly adequate. As physical objects from cars to refrigerators to personal assistants are computerized and seamlessly integrated into our lives, these issues will become enormous. Actually, they already are. The author believes these complications to be fixable bugs.

The main problem with his reasoning is it assumes there must be reasonable answers to vexing Digital Era questions. That’s not necessarily so. Perhaps there’s no taming the anarchy of a “smart” world that’s super-connected. Certainly Kasparov’s arch-nemesis Vladimir Putin wouldn’t have been able to influence the Brexit and U.S. Presidential votes without linked computers, those chaos agents. Mayhem may be baked so deeply into the new tools that the havoc is inseparable–and insuperable. It could even be that a highly technological society, a deeply connected and heavily sensored one, ultimately destroys itself. I don’t believe that scenario plausible, but it’s irresponsible to not consider it possible.

Those challenges are just the ones we’re aware of. Nobody knew a century ago that the internal combustion engine would soon create an existential threat. Tomorrow’s tools will be far more powerful and so probably will be their unintended consequences.

· · ·

In one passage, Kasparov asserts that his quote from 1989 in which he predicted AI would become world champion before a woman did wasn’t sexist. Well, perhaps that’s so, but the suspicion seems more understandable if you know the context the author has omitted. If anyone in 1989 suspected Kasparov was deeply sexist that’s because in 1989 Kasparov was deeply sexist.

From a Playboy Interview that year:

Playboy:

How about women chess players?

Garry Kasparov:

Well, in the past, I have said that there is real chess and women’s chess. Some people don’t like to hear this, but chess does not fit women properly. It’s a fight, you know? A big fight. It’s not for women. Sorry. She’s helpless if she has men’s opposition. I think this is very simple logic. It’s the logic of a fighter, a professional fighter. Women are weaker fighters.

There is also the aspect of creativity in chess. You have to create new ideas. That’s quite difficult, too. Chess is the combination of sport, art and science. In all these fields, you can see men’s superiority. Just compare the sexes in literature, in music or in art. The result is, you know, obvious. Probably the answer is in the genes.

Playboy:

Do you realize that you’re expressing a sexist point of view, and that Western women will be enraged by it?

Garry Kasparov:

Yes, but I’m not concerned. I’m sure that women can do many things better than men in many fields. I think it’s wrong to want to be compared all the time, to want to be equal in everything. Men and women are different.•

Two daughters and two decades later, Kasparov was far more enlightened when questioned by the same magazine:

Playboy:

Why are there relatively few women chess players?

Garry Kasparov:

Tradition. How many women composers are there? Architects? Things are changing in this. We have Judit Polgar, who proved a woman can make the top 10, though she didn’t come even close to number one.•

Okay, sexism would have been a more apt word choice than tradition, but I don’t blame Kasparov from wanting to recoil from his earlier misogyny, seeing how he’s apparently grown past it. But disappearing this failing removes an important lesson: Humans, like intelligent machines, can learn and grow in surprising ways.

· · ·

In “A Brutal Intelligence: AI, Chess, and the Human Mind,” Nicholas Carr reviews Kasparov’s title for the Los Angeles Review of Books, making interesting observations about the limits of blunt-force computing and the very nature of chess. Carr notes that our type of thinking will likely be beyond the reach of computers into the long-term future but worries that “brutally efficient calculations” will become more valued than the inexpressible nuances of human thought. An excerpt:

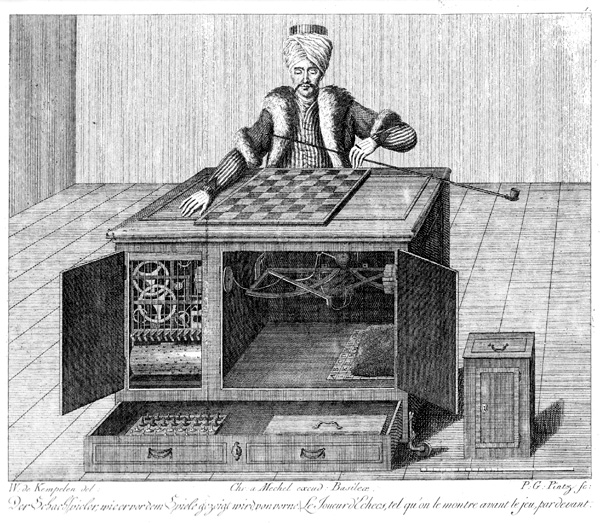

The history of computer chess is the history of artificial intelligence. After their disappointments in trying to reverse-engineer the brain, computer scientists narrowed their sights. Abandoning their pursuit of human-like intelligence, they began to concentrate on accomplishing sophisticated, but limited, analytical tasks by capitalizing on the inhuman speed of the modern computer’s calculations. This less ambitious but more pragmatic approach has paid off in areas ranging from medical diagnosis to self-driving cars. Computers are replicating the results of human thought without replicating thought itself. If in the 1950s and 1960s the emphasis in the phrase “artificial intelligence” fell heavily on the word “intelligence,” today it falls with even greater weight on the word “artificial.”

Particularly fruitful has been the deployment of search algorithms similar to those that powered Deep Blue. If a machine can search billions of options in a matter of milliseconds, ranking each according to how well it fulfills some specified goal, then it can outperform experts in a lot of problem-solving tasks without having to match their experience or insight. More recently, AI programmers have added another brute-force technique to their repertoire: machine learning. In simple terms, machine learning is a statistical method for discovering correlations in past events that can then be used to make predictions about future events. Rather than giving a computer a set of instructions to follow, a programmer feeds the computer many examples of a phenomenon and from those examples the machine deciphers relationships among variables. Whereas most software programs apply rules to data, machine-learning algorithms do the reverse: they distill rules from data, and then apply those rules to make judgments about new situations.

In modern translation software, for example, a computer scans many millions of translated texts to learn associations between phrases in different languages. Using these correspondences, it can then piece together translations of new strings of text. The computer doesn’t require any understanding of grammar or meaning; it just regurgitates words in whatever combination it calculates has the highest odds of being accurate. The result lacks the style and nuance of a skilled translator’s work but has considerable utility nonetheless. Although machine-learning algorithms have been around a long time, they require a vast number of examples to work reliably, which only became possible with the explosion of online data. Kasparov quotes an engineer from Google’s popular translation program: “When you go from 10,000 training examples to 10 billion training examples, it all starts to work. Data trumps everything.”

The pragmatic turn in AI research is producing many such breakthroughs, but this shift also highlights the limitations of artificial intelligence. Through brute-force data processing, computers can churn out answers to well-defined questions and forecast how complex events may play out, but they lack the understanding, imagination, and common sense to do what human minds do naturally: turn information into knowledge, think conceptually and metaphorically, and negotiate the world’s flux and uncertainty without a script. Machines remain machines.

That fact hasn’t blunted the public’s enthusiasm for AI fantasies.•