Yawning wealth inequality seems to be contributing to contemporary political and cultural chaos, so the 1% in the U.S. and Europe has been subject to intense scrutiny over the past few years, even if the result has been more analysis than policy action. In the case of Brazil, the beleaguered host of the soon-to-be Summer Games, distribution is so out of wack you need look no further than the excesses of the .0001% to understand how stacked a deck can be.

Proof comes in the pages of Alex Cuadros’ Brazillionaires, which examines the nation’s super-rich and how they got be that way. The short answer is that oligarchs were deemed useful by economic reformers who saw a quick way to lift millions from poverty, though the long-term effects of the deal with the devil are far more complicated.

In “Brazil’s Billionaire Problem,” Patrick Iber’s smart New Republic review of the book, the critic looks at South America’s largest state and sees a microcosm. An excerpt:

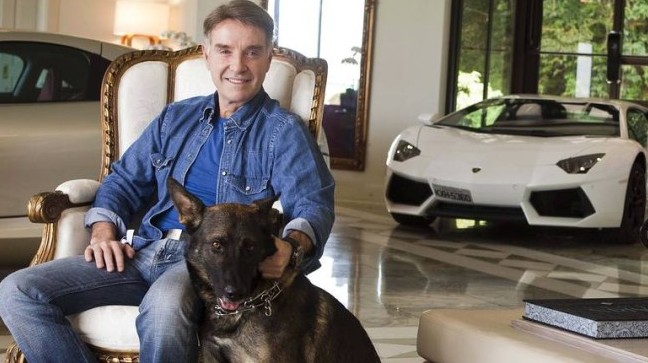

The most important billionaire to the book is unquestionably Eike Batista. Eike, as he is known, rose as high as the global number 8 on the Bloomberg list of billionaires, valued at over $30 billion dollars. He was open about his ambitions to become the world’s richest man. Eike is a champion speedboat racer, has state-of-the-art hair implants, and was once married to Luma de Oliveira, a Playboy model and carnaval queen. One of their sons, Thor Batista, documents his enormous muscular torso on Instagram and, until not long ago, drove a Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren valued at more than a million US dollars. Eike and his family could hardly be more representative of the billionaire playboy lifestyle of the global ultra-wealthy.

Eike also serves as a symbol of the problems of today’s Brazil, and about half of the chapters in Brazillionaires are devoted to him. In spite of what would seem to be fundamental differences in outlook and ideology, Eike forged a pragmatic working relationship with the governments of the center-left Workers’ Party. Until President Dilma Roussef was suspended from office by hostile legislators this May, the country had been governed by the center-left Workers’ Party since 2003, first under the metalworker and union organizer Luís Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2011) and then under Dilma (2011-2016). Before Lula took office, Brazil’s wealthy worried about what would happen when a Lula, a former socialist, assumed power. Eike himself described it as a regression. But Lula was determined to break the association of left-wing rule with economic chaos, and built alliances with Brazilian oligarchs.

Lula embraced a developmentalist program that Cuadros describes as “wanting to bring the nation not so much into the twenty-first century, with tech and high finance, but into the twentieth, with ports, dams, and big, basic Brazilian companies.” Because Eike controlled a suite of interrelated companies, mostly in the mining and gas sectors, and had made big bets on offshore drilling, he received major loans from Brazil’s state-controlled development bank. He grew close to Lula.

Corruption is almost an expected part of business and political deals in Brazil, and Eike, though often portrayed as an “American-style”, “self-made” entrepreneur, was in no way exceptional. He helped finance a flattering biopic about Lula and spent quarter of a million dollars at an auction to purchase a suit Lula had worn to his inauguration. But in spite of evidence of corruption and conflicts of interest through the political system, for a time everyone seemed to be benefitting. Brazil’s economy made enormous strides. The middle class grew and quality of life standards among the poor improved dramatically. Malnutrition was cut in half. One of Lula signature programs, Bolsa Família, provides direct cash transfers to the poor, partially in exchange for children’s school attendance. Many of the billionaires Cuadros interviewed justified their wealth with some version of the “what’s good for GM is good for the country” argument. Most Brazilians found the approach acceptable: Lula left office with an approval rating over eighty percent.

But problems emerged by 2013.•