Over at Edge, economist Richard Thaler asked the science site’s contributors for responses to this question: “The flat earth and geocentric world are examples of wrong scientific beliefs that were held for long periods. Can you name your favorite example and for extra credit why it was believed to be true?”

I think philosopher Eduardo Salcedo-Albarán had the most intriguing and humane answer:

“Phrenology and lobotomy. Even when these were not scientific paradigms, they clearly illustrate how science affects people’s life and morality. For those not engaged in the scientific work, it is easy to forget that technology, and a great part of the western contemporary culture, results from science. However, people tend to interpret scientific principles and findings as strange matters that have nothing to do with everyday life, from gravity and evolution, to physics and pharmacology.

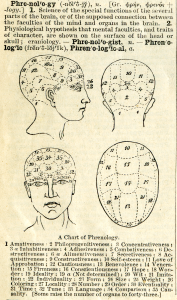

Phrenology is defined as the ‘scientific’ relation between the skull’s shape and behavioral traits. It was applied to understand, for example, the reason for the genius of Professor Samuel B. F. Morse. However, it was also applied in prisons and asylums to explicate and predict criminal behaviors. In fact, it was also assumed that the skull’s shape explained incapacities to act according to the law. If you were spending your life in an asylum or a prison in 19th century because of a phrenological ‘proof’ or ‘argument,’ you could perfectly understand how important science in your life is, even if you are not a scientist. Even more, if you were going to be a lobotomy’s patient in the past century.

In 1949, Antonio Egas Moniz achieved the Nobel Prize of Physiology and Medicine for discovering the great therapeutic value of lobotomy, a surgical procedure that, in its transorbital versions, consisted of introducing an ice pick through the eye’s orbit to disconnect the prefrontal cortex. Thousands of lobotomies were performed between the decade of 1940’s and the first years of 1960’s, including Rosemary Kennedy, sister of President John F. Kennedy, on the list of recipients; all of them with the scientific seal of a Nobel Prize. Today, half a century later, it seems unthinkable to apply such a ‘scientific’ therapy. I keep asking myself: ‘what if’ a mistake like this one is adopted today as policy on public health?

Science affects people’s lives directly. A scientific mistake can send you to jail or break your brain into pieces. It also seems to affect the kinds of moral stances that we adopt. Today, it would be morally reprehensible to send someone to jail because of the shape of his head, or to perform a lobotomy. However, 50 or 100 years ago it was morally acceptable. This is why we should spend more time thinking of practical issues, like scientific principles, scientific models and scientific predictions as a basis for public health and policy decisions, rather than guessing about what is right or wrong according to god’s mind or the unsubstantiated beliefs presented by special interest groups.”