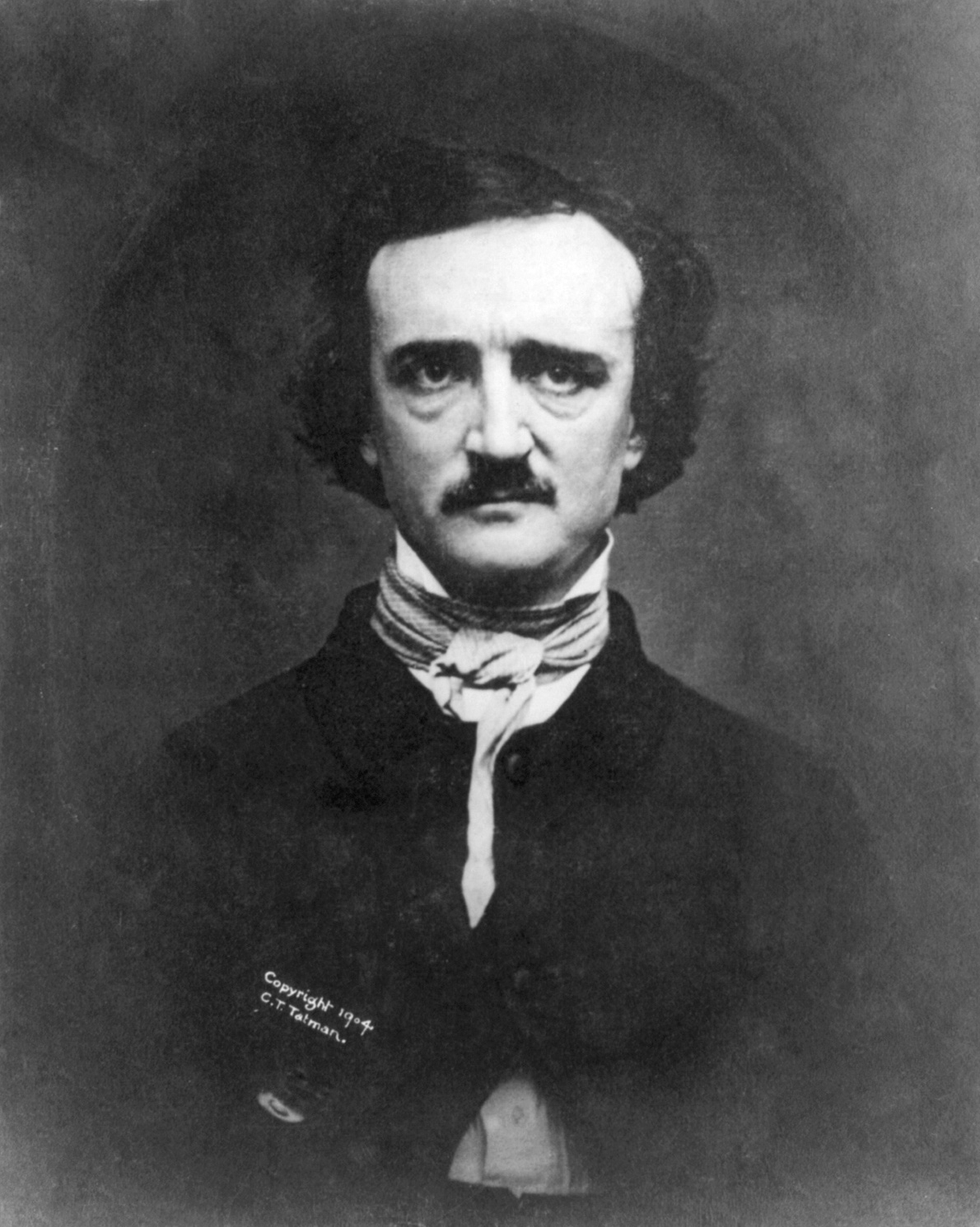

In the New York Review of Books, a contemporary American literary giant, Marilynne Robinson, takes on one of our greatest ever, Edgar Allan Poe, focusing mostly on his sole novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket.

Poe died mysteriously and horribly, a sad and appropriate end, as if a premature burial had always awaited him. That he was able to squeeze so much genius into such a short life and so narrow an aesthetic is miraculous. An excerpt:

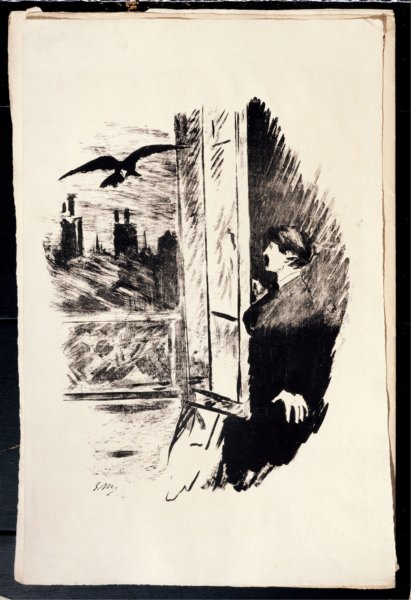

The word that recurs most crucially in Poe’s fictions is horror. His stories are often shaped to bring the narrator and the reader to a place where the use of the word is justified, where the word and the experience it evokes are explored or by implication defined. So crypts and entombments and physical morbidity figure in Poe’s writing with a prominence that is not characteristic of major literature in general. Clearly Poe was fascinated by popular obsessions, with crime, with premature burial. Popular obsessions are interesting and important, of course. Collectively we remember our nightmares, though sanity and good manners encourage us as individuals to forget them. Perhaps it is because Poe’s tales test the limits of sanity and good manners that he is both popular and stigmatized. His influence and his imitators have eclipsed his originality and distracted many readers from attending to his work beyond the more obvious of its effects.

Poe’s mind was by no means commonplace. In the last year of his life he wrote a prose poem, Eureka, which would have established this fact beyond doubt—if it had not been so full of intuitive insight that neither his contemporaries nor subsequent generations, at least until the late twentieth century, could make any sense of it. Its very brilliance made it an object of ridicule, an instance of affectation and delusion, and so it is regarded to this day among readers and critics who are not at all abreast of contemporary physics. Eureka describes the origins of the universe in a single particle, from which “radiated” the atoms of which all matter is made. Minute dissimilarities of size and distribution among these atoms meant that the effects of gravity caused them to accumulate as matter, forming the physical universe.

This by itself would be a startling anticipation of modern cosmology, if Poe had not also drawn striking conclusions from it, for example that space and “duration” are one thing, that there might be stars that emit no light, that there is a repulsive force that in some degree counteracts the force of gravity, that there could be any number of universes with different laws simultaneous with ours, that our universe might collapse to its original state and another universe erupt from the particle it would have become, that our present universe may be one in a series.

All this is perfectly sound as observation, hypothesis, or speculation by the lights of science in the twenty-first century. And of course Poe had neither evidence nor authority for any of it. It was the product, he said, of a kind of aesthetic reasoning—therefore, he insisted, a poem. He was absolutely sincere about the truth of the account he had made of cosmic origins, and he was ridiculed for his sincerity. Eureka is important because it indicates the scale and the seriousness of Poe’s thinking, and its remarkable integrity. It demonstrates his use of his aesthetic sense as a particularly rigorous method of inquiry.•