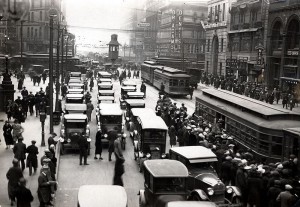

We definitely need GMOs since even if we were friendly to our environment, and we’re certainly not, eventually the climate that allows our agrarian culture would change, and then we would be staring at famine. Even with this scary reality, no one wants to trust Monsanto with the process, the company’s name having become a curse word. From “Inside Monsanto, America’s Third-Most-Hated Company,” Drake Bennett’s Bloomberg Businessweek piece:

“The 32-year-old farmer sits in the bouncing tractor cab, wearing a hooded sweatshirt, a baseball cap, jeans, a Bluetooth headset, and a look of fatigue. The steering wheel is folded up out of the way. When the tractor nears the end of a row, its autopilot beeps cheerfully, and he taps a square on one of the touchscreens to his right. The tractor executes a turn, and he goes back to surfing the Web, watching streaming videos, or checking the latest corn prices. ‘You see how boring this gets?’ [Dustin] Spears asks. ‘I’ll be listening to music for 12 hours. I’ll refresh my Twitter timeline, like, a hundred thousand times during the day.’

Spears is an early adopter who upgrades his equipment every 12 months (next year’s tractor will have a fridge in the cab, he says) and who just bought a drone to monitor his fields. He can afford to: Corn prices are high, and farmers like him can take home hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Still, he thinks such technologies—the smart planter software and sensor array, the iPad app offering planting and growing advice—are only going to get more common. So does the company that makes many of those tools, as well as the high-tech seeds Spears is planting: Monsanto, one of the most hated corporations in America.

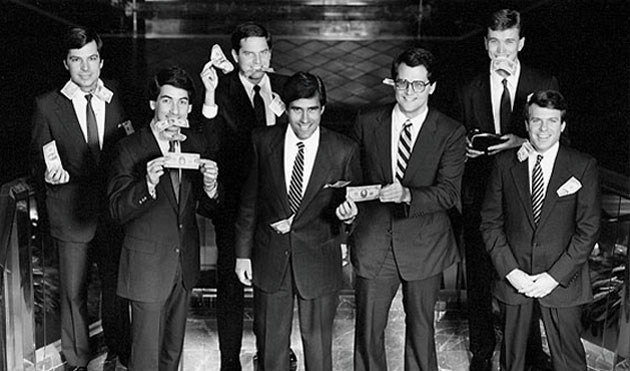

In a Harris Poll this year measuring the ‘reputation quotient’ of major companies, Monsanto ranked third-lowest, above BP and Bank of America and just behind Halliburton. For much of its history it was a chemical company, producing compounds used in electrical equipment, adhesives, plastics, and paint. Some of those chemicals—DDT, Agent Orange, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)—have had long and controversial afterlifes. The company is best known, however, as the face of genetically modified organisms, or GMOs. …

Technology has already dumbed down everything from flying an airliner to filing one’s taxes, and in so doing made those tasks safer and more efficient. But food feels different to many people. ‘You know, when this data-intensive system recommends you buy a certain seed, it’s going to be a Monsanto seed,’ says the author Michael Pollan, a prominent critic of industrial agriculture. ‘So I have a strong objection to letting any one company exert that much control over the food supply. It depends on the wisdom of one company, and in general I’d rather distribute that wisdom over a great many farmers.'”