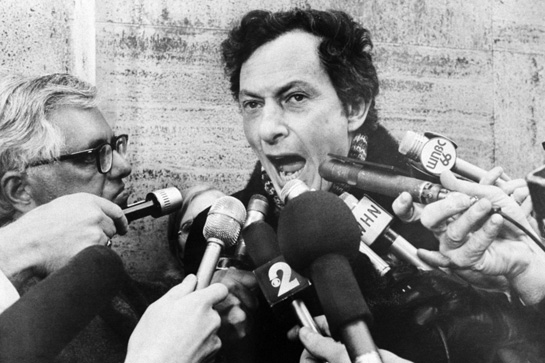

Before it became apparent that Geraldo Rivera really just wanted to give the whole world a free mustache ride, he was a respected, muckraking journalist who filmed a sensational and righteous report about abuses at Willowbrook. He instantly became a national name and soon had other opportunities, including a really good if sporadic 1973-75 late-night talk show, Good Night America.

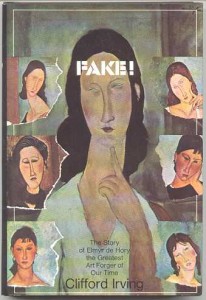

In a summer 1974 episode, he spoke to someone I’m fascinated with in Clifford Irving, who’d written a 1969 book about art forger Elmyr De Hory before bringing out another volume in 1972, one in which he pretended that the reclusive Howard Hughes had collaborated with him on an autobiography. McGraw-Hill took the bait and gave him a boatload of cash for the “exclusive,” but the Hughes ruse was soon exposed. Irving was operating in an era when people still distinguished between fact and fiction, so his career went into a Dumpster for awhile.

Orson Welles, an infamous hoaxer himself, made a brilliant, serendipitous cine-essay, F Is for Fake, about the scandal as it unfolded, and Irving was grilled at the time by everyone from Mike Wallace to Abbie Hoffman. In a marriage-themed show, Geraldo speaks to Irving and his wife Edith about the toll on their relationship caused by the fraud’s fallout, which included prison sentences for them both. (They had just been released on parole when this program was filmed.)

The host also speaks to Sly and Kathy Stone about their wedding ceremony in front of more than 20,000 people at Madison Square Garden and shows footage of the event. The final segment is with comedian Robert Klein and his then-spouse, the opera singer Brenda Boozer. Loathsome Henny Youngman is the guest announcer, serving up Zsa Zsa Gabor jokes. Holy Mother of God! Watch it here.•