Pundits on Twitter and in the opinion pages are of two vastly different minds about the future of the Democrats: After Trump’s election–no matter how crooked it may have been–the party either needs to become far more centrist or must move way to the left. Either it focuses on the white working class and rurals or goes all in on minorities and urbans. Both stances would have a large impact on the type of policy we have, but when it comes to winning, the two camps may be overthinking things.

Identity politics are so important in our media-saturated society that having a candidate who speaks to key issues with authenticity (or at least projects that quality) is probably the most vital ingredient. I’m not saying it should be that way but just that it is.

The most successful Democratic Party is likely one that makes an effort to appeal to working-class people across the borders of race and religion, not an impossible feat. Focus on healthcare and the issues that face us all, and follow up in those areas if elected.

· · ·

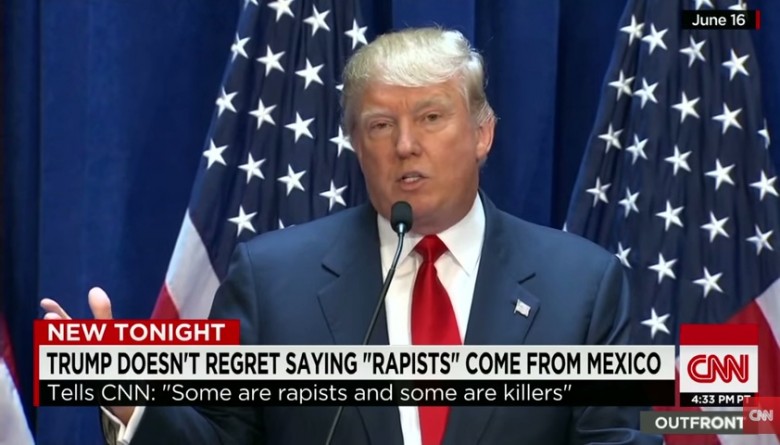

Naomi Klein has her positives and negatives, but I think she makes a salient point in a Spiegel interview conducted by Christoph Scheuermann which coincided with the just-completed G-20 summit. In an America which has spent decades assailing regulations (Jimmy Carter was just as enthusiastic in this area as Ronald Reagan), has had candidates from both sides of the aisle attacking government (though Republicans with a religious zeal) and has failed to deliver on big promises thanks to fractiousness and dysfunction, billionaires are often viewed as private-sector saviors to make up for all that we lack. That goes for the sweater-clad, avuncular 2.0 version of Bill Gates, who was a raging asshole during his Microsoft reign, or Donald Trump, a make-believe businessman who screams like Gordon Ramsey and wants to bake the world.

An excerpt:

Spiegel:

Twenty years ago, you helped launch anti-globalization with your book, No Logo. Today it has become almost fashionable to campaign against the consequences of unrestrained capital flows. Has your criticism become part of the mainstream?

Naomi Klein:

I’ve never liked the term “globalization,” it sounds like you’re against the world. What we’re really talking about is the globalization of a specific economic model. The political right is hijacking legitimate frustration about people’s jobs, living standards, the ability to change the direction of the country you’re living in. This is the feeling that Trump, the Brexiters and Marine Le Pen are all tapping into, and they’re mixing it with xenophobic hatred of anything international, with hypernationalism and a toxic anti-immigrant, anti-United Nations, anti-everything global sentiment. The right has been able to do this because centrist political parties abandoned their traditional opposition to these types of policies. They ended up pushing the agenda even further, creating a vacuum for the right to go in. It’s very dangerous. …

Spiegel:

You describe Trump’s rise as an almost inevitable consequence of the neoliberal project. Aren’t you fighting the same old enemy again?

Naomi Klein:

Many liberals treat Trump like a martian who fell from the sky, who has nothing to do with the rest of us. I don’t think that’s true. The mainstream American culture was creating a context that Trump was uniquely qualified to exploit. The coverage of elections has come to resemble a reality show. It’s all about ratings, less about policy and content. That had started long before Trump ran for president. But if elections are nothing more than infotainment, then a reality TV show star is going to be much better at it than a traditional politician because they have those skills. There’s also this billionaire savior complex that has been building up around figures like Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Michael Bloomberg, all liberal heroes. We’ve increasingly been outsourcing our big problems to foundations run by billionaires — pandemics, a failing education system — rather than treating these as collective problems for democracies to solve. …

Spiegel:

What must happen for Americans to not vote for Trump again?

Naomi Klein:

It has to be a two-fold argument. First, he lied to you when he said he’d protect your Social Security and your health care. Secondly, we have to have candidates who are going to bring universal public health care, make sure that your kids can afford to go to university and are going to create huge numbers of jobs by investing in public infrastructure.

Spiegel:

Many Trump voters lost their jobs because of globalization. Is that a cynical consequence of your own criticism?

Naomi Klein:

The only person talking about working-class voters was Donald Trump. That is the tragedy, not that they voted for him. It’s an absurdity that Trump could pose as a savior of the working class, from his golden tower and his golden throne, but it shows how people have been abandoned by the Democrats. A lot of people just wanted to raise the middle finger to Washington. I do believe that there’s a portion of Trump’s working class base that is reachable. The terrain is fertile.•