It’s just perfect that Monopoly, which brought cutthroat capitalism to the living room, allowing you to bankrupt grandma, was birthed through dubious business deals. In Mary Pilon’s new book, The Monopolists, the author traces the key role in the game’s invention of Elizabeth Magie, whose Landlord’s Game, which preceded Charles Darrow’s blockbuster, has largely been lost to history. From James McManus in the New York Times:

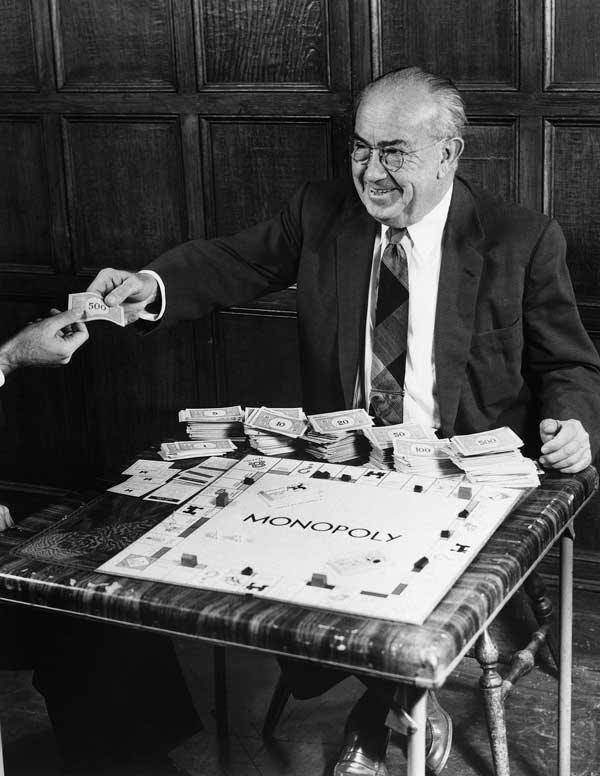

Our favorite board game, of course, is Monopoly, which has also gone global, and for similar reasons. Played by everyone from Jerry Hall and Mick Jagger to Carmela and Tony Soprano, it apparently scratches an itch to wheel and deal few of us can reach in real life. The game is sufficiently redolent of capitalism that in 1959 Fidel Castro ordered the destruction of every Monopoly set in Cuba, while these days Vladimir Putin seems to be its ultimate aficionado.

What dyed-in-the-wool free marketeer invented this cardboard facsimile of real estate markets, and who owns it now? From whose ideas did it evolve? These are the questions Mary Pilon, formerly a reporter at The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, proposes to answer in her briskly enlightening first book, The Monopolists. For decades the official story, slipped into every Monopoly box, was that Charles Darrow, an unemployed salesman, had a sudden light-bulb moment about a game to amuse his poor family during the Depression. After selling it to Parker Brothers in 1935, he lived lavishly ever after on the proceeds.

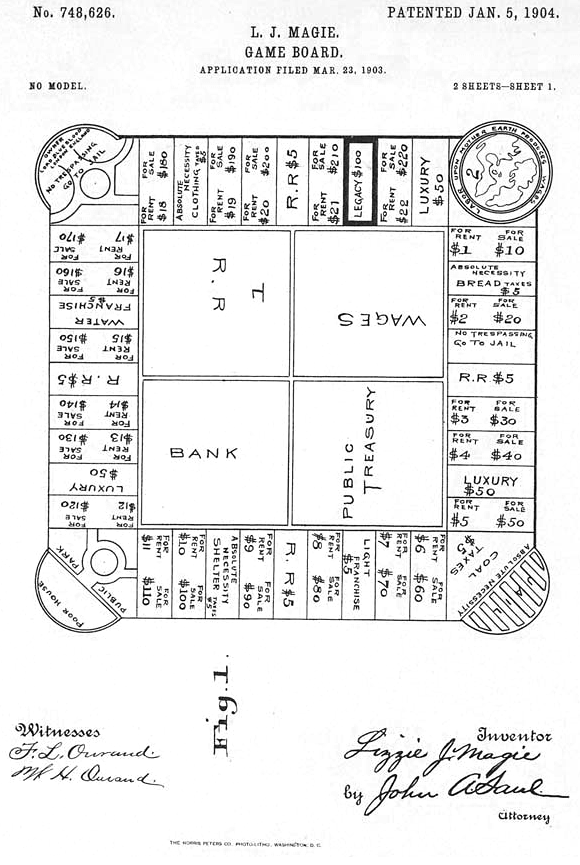

To trace how far removed this was from the truth, Pilon introduces Elizabeth Magie. Born in 1866, she was an unmarried stenographer whose passions included politics and — even more rare among women of that era — inventing. In 1904 she received a patent for the Landlord’s Game, a board contest she designed to cultivate her progressive, proto-feminist values, and as a rebuke to the slumlords and other monopolists of the Gilded Age.

Her game featured spaces for railroads and rental properties on each side of a square board, with water and electricity companies and a corner labeled “Go to Jail.” Players earned wages, paid taxes; the winner was the one who best foiled landlords’ attempts to send her to the poorhouse. Magie helped form a company to market it, but it never really took off. The game appealed mostly to socialists and Quakers, many of whom made their own sets; other players renamed properties and added things like Chance and Community Chest cards. Even less auspiciously for Magie, many people began referring to it as “monopoly” and giving it as gifts. Then in 1932, Charles Darrow received one with spaces named for streets in Atlantic City.

No light bulb necessary.•