Magical thinking is not limited to the religious, as the secular likewise often imbue objects with some degree of sentience, as psychologist Bruce Hood points out in a Wired UK piece by Katie Collins. The opening:

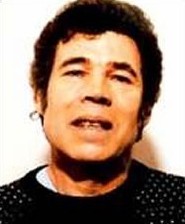

“‘I’m a collector; I collect unusual things,’ says University of Bristol psychologist Bruce Hood speaking at WIRED2014 in London. He asks the audience if they would wear a beautiful cashmere cardigan that he had collected, that was freshly washed and that was once owned by a famous individual. Many raise their hands, but they slink down again when Hood says the cardigan belonged to the serial killer Fred West.

It is not true — in fact the cardigan is one of Hood’s own — but he is making a point: many people hold the belief that a piece of clothing that has come into close contact with a serial killer has somehow been contaminated by the immoral acts committed by its owner. ‘That is what I call supernatural,’ he says. Hood is interested in why we are prepared to believe the unbelievable. The killer cardigan is not connected with religious belief he points out, but that doesn’t stop the majority of people feeling that there’s a hidden property in the clothing that would stop them wearing it.

Hood explains that this is a phenomenon known in psychology as ‘essentialism.’ ‘This is what I’m obsessed with at the moment,’ he says. It is an idea that can be traced back to the days of Plato and that is based on the concept that people can have a strong emotional connections to objects; that they can be imbibed with an ‘essence.'”