Can’t say I’m unduly focused on superintelligence posing an existential threat to our species in the immediate future, especially since so-called Weak AI is already here and enabling its own alarming possibilities: ubiquitous surveillance, attenuated democracy and a social fabric strained by disappearing jobs. We may very well require these remarkably powerful tools to survive tomorrow’s challenges, but we’d be walking blind to not accept that they’re attended by serious downsides.

Deep Learning will be particularly tricky, expressly because it’s a mysterious method that doesn’t allow us to know how it makes its leaps and gains. Demis Hassabis, the brilliant DeepMind founder and the field’s most famous practitioner, has acknowledged being “pretty shocked,” for instance, by AlphaGo’s unpredictable gambits during last year’s demolition of Lee Sedol. Hassibis, who has sometimes compared his company to the Manhattan Project (in scope and ambition if not in impact), has touted AI’s potentially ginormous near-term benefits, but tomorrow isn’t all that’s in play. The day after also matters.

The neuroscientist is fairly certain we’ll have Artificial General Intelligence inside a century and is resolutely optimistic about carbon and silicon achieving harmonic convergence. Similarly sanguine on the topic these days is Garry Kasparov, the Digital Age John Henry who was too dour about computer intelligence at first and now might be too hopeful. The human-machine tandem he foresees may just be a passing fancy before a conscious uncoupling. By then, we’ll have probably built a reality we won’t be able to survive without the constant support of our smart machines.

Hassibis, once a child prodigy in chess, wrote a Nature review of Kasparov’s new book, Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins. (I’m picking up the title tomorrow, so I’ll write more on it later.) An excerpt:

Chess engines have also given rise to exciting variants of play. In 1998, Kasparov introduced ‘Advanced Chess’, in which human–computer teams merge the calculation abilities of machines with a person’s pattern-matching insights. Kasparov’s embrace of the technology that defeated him shows how computers can inspire, rather than obviate, human creativity.

In Deep Thinking, Kasparov also delves into the renaissance of machine learning, an AI subdomain focusing on general-purpose algorithms that learn from data. He highlights the radical differences between Deep Blue and AlphaGo, a learning algorithm created by my company DeepMind to play the massively complex game of Go. Last year, AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol, widely hailed as the greatest player of the past decade. Whereas Deep Blue followed instructions carefully honed by a crack team of engineers and chess professionals, AlphaGo played against itself repeatedly, learning from its mistakes and developing novel strategies. Several of its moves against Lee had never been seen in human games — most notably move 37 in game 2, which upended centuries of traditional Go wisdom by playing on the fifth line early in the game.

Most excitingly, because its learning algorithms can be generalized, AlphaGo holds promise far beyond the game for which it was created. Kasparov relishes this potential, discussing applications from machine translation to automated medical diagnoses. AI will not replace humans, he argues, but will enlighten and enrich us, much as chess engines did 20 years ago. His position is especially notable coming from someone who would have every reason to be bitter about AI’s advances.•

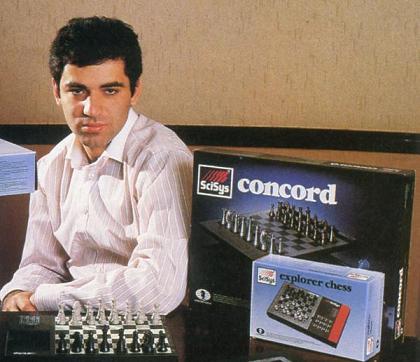

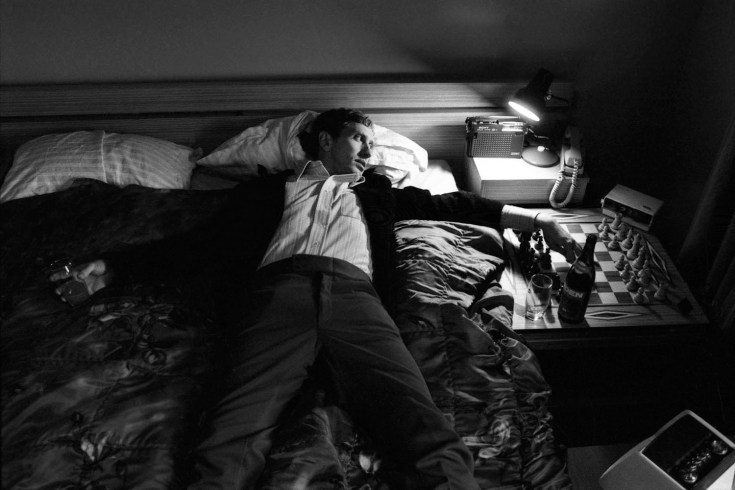

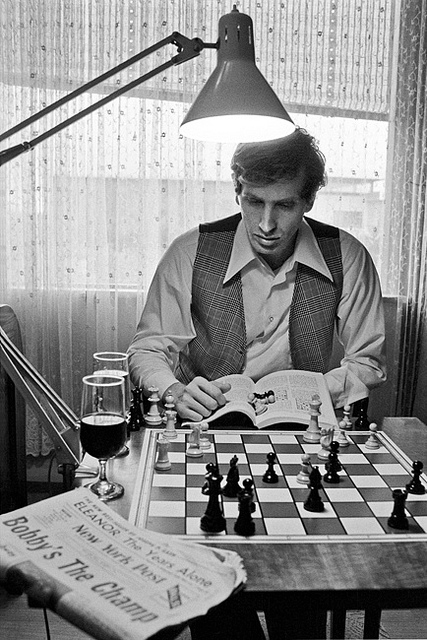

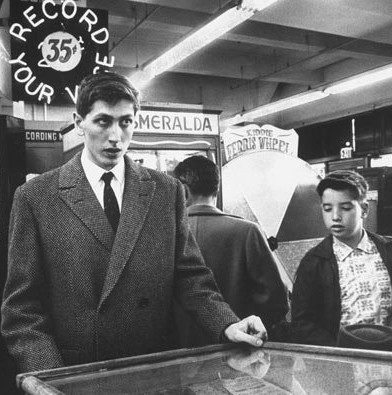

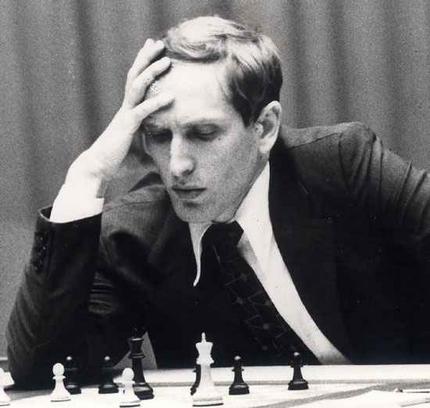

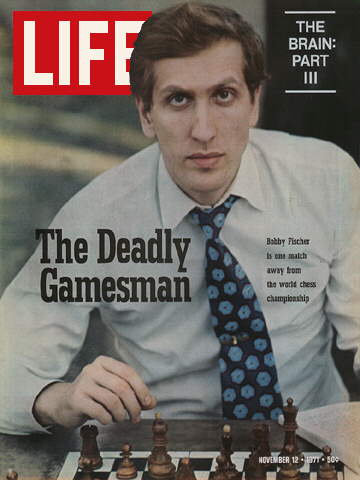

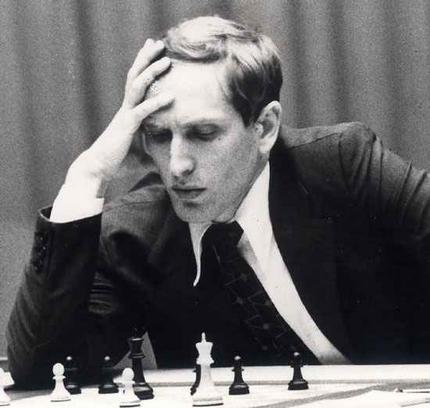

Two quainter examples of technology crossing wires with chess.

In 1989, Kasparov, in London, played a remote match via telephone with David Letterman.

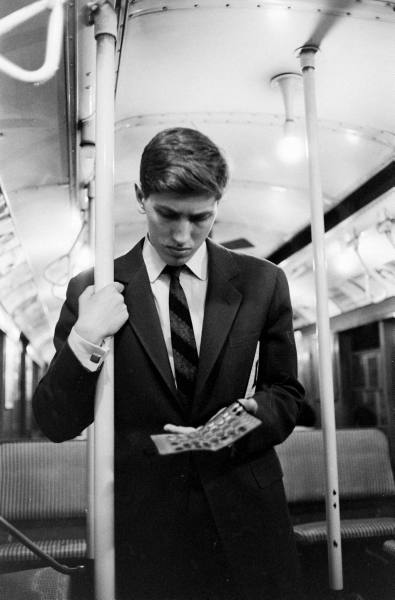

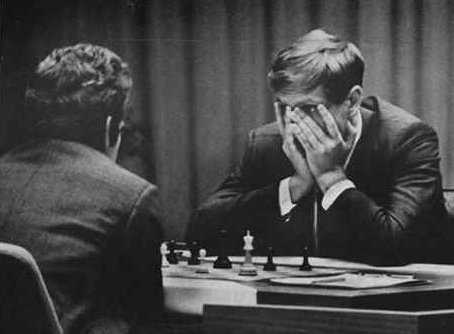

In 1965, Bobby Fischer, in NYC, played via Teletype in a chess tournament in Havana.