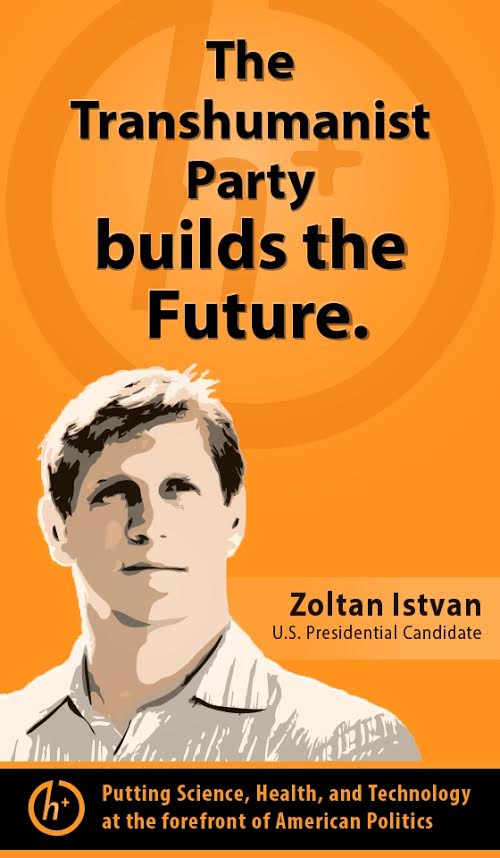

Transhumanist Presidential candidate Zoltan Istvan wants to do things with public lands and prisoners’ brains that I staunchly disagree with, but I ‘ve followed his colorful campaign of outré ideas with great interest. Perhaps I’d have a different feeling in the pit of my stomach if he were a serious contender, but his platform is interesting at a safe distance. At any rate, he’s the only candidate desiring elective surgery to amputate his limbs and replace them with robotic ones. Flat-tax proposals pale by comparison.

In an excellent New Yorker piece, Andrew Marantz profiles a candidate that I (and, probably, you) did not vote for today, revealing details about Istvan’s failed audition to be Gary Johnson’s running mate and his future political plans. The opening:

After watching the least popular Presidential candidates in modern history fight for the country’s highest office, one can’t help wondering whether the problem isn’t the political system but the species itself. Can’t we think bigger? Zoltan Istvan was in town recently, campaigning as the Presidential nominee of the Transhumanist Party. He was on track to appear on the ballot in zero states. “Politicians keep having the same old arguments about tax policy and Social Security,” he said. “Transhumanists want to talk about how science can help us radically transform the human experience, how we can cure death and disease and upload our consciousness into the cloud, things like that.” He was on a street corner in SoHo. It was raining, but he had decided to forgo an umbrella; the spokes can put an eye out, and bionic-eye implants won’t be perfected for at least five years.

He ducked into the Housing Works Bookstore Café, on Crosby Street, and ordered a coffee. Istvan is blond, Ken-doll handsome, and barrel-chested, and the paper cup looked tiny in his hand. “With some of the new robotic-arm prototypes, you get all kinds of cool functionality,” he said. “I could be warming up this cup right now, just with my fingers. Or you could add weapons, flashlights—like a Swiss Army knife. I can’t wait to cut off my arm and get a prosthetic. My wife said she’d only be O.K. with it if it looks and feels like a human arm, which is understandable, I guess.” His wife, Lisa, is an ob-gyn. When they met, on Match.com, Istvan was an entrepreneur with a small real-estate fortune, living in Marin County. After they married, he began driving across the country in a bus shaped like a coffin, protesting death, while Lisa mostly stayed in California with their two daughters. Her attitude toward transhumanism seems to be one of forbearance at best.

Istvan dragged a chair toward a wall of science-fiction novels. “I wrote a sci-fi book once,” he said. It was an Ayn Rand-esque manifesto called The Transhumanist Wager. He added, “I don’t talk about it much these days, because there’s so much authoritarianism in it.”

A man with a wild beard and half a dozen shopping bags got up, and Istvan moved to claim his table. “You a public speaker or something?” the man asked.

“Yeah, sort of,” Istvan said. “I’m running for President.”

“Cool,” the man said. “I’m a filmmaker.”•