Like a lot of comedians, Abbie Hoffman was sad. After gaining international fame for railing against capitalism and the American war machine during the 1960s, he lived on the lam (wanted but not desired), was covered in an avalanche of blow, suffered from clinical depression and was unable to reinvent himself when he finally resurfaced. He didn’t want to live in the past but couldn’t seem to find a place in the present. His was a great trick that couldn’t be performed twice. Sad and broken, he took his own life in 1989. From the People article “A Troubled Rebel Chooses A Silent Death“:

“In the sunny, plant-filled apartment where Abbie Hoffman ended his life with a massive overdose of phenobarbital, the artifacts on the wall bespoke decades of rebellion: a poster of the Grateful Dead, another of a raised fist with the word STRIKE!, a bumper sticker reading VOTE REPUBLICAN. IT’S EASIER THAN THINKING, a photo of a young Hoffman wearing a Chicago policeman’s shirt.

Summoned to this corner of pastoral Bucks County, Pa., six years ago by an environmental group that wanted his help battling the diversion of the Delaware River water to cool a nuclear reactor, Hoffman told an interviewer in 1987 that he was happy to ‘live and die here fighting the Philadelphia Electric Company-it’s just like the ’60s for me.’

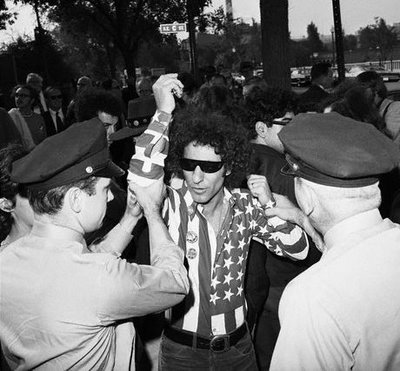

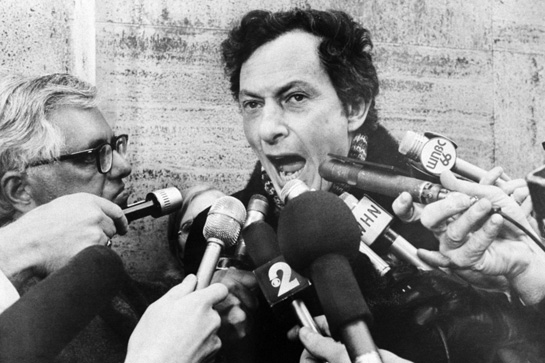

But it was not just like the ’60s. In that theatrical era, young Abbie Hoffman held center stage. A self-styled ‘Groucho Marxist’ and co-founder of the Youth International Party (supporters were dubbed yippies), which existed mostly in his imagination, he was the antiwar movement’s mad genius of media events. He disrupted business on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange by tossing dollar bills from the balcony. He rallied 50,000 anti-Vietnam War demonstrators to levitate the Pentagon. He nominated a pig—Pigasus—for President when thousands of protesters converged on Chicago to demonstrate at the 1968 Democratic Convention. The violence in the streets there led to the most famous political trial of the decade, as Hoffman and his Chicago Eight co-defendants were charged in 1969 with conspiracy to incite riot.

They ultimately beat the charges but not before turning Judge Julius Hoffman’s courtroom into a countercultural circus: Abbie somersaulted into court one day and wore judicial robes another. ‘Where do you reside?’ his lawyer asked him on the witness stand. ‘I live in Woodstock Nation,’ he replied. ‘It is a nation of alienated young people. We carry it around with us as a state of mind…. It is a nation dedicated to…the idea that people should have better means of exchange than property or money.’

Just what that ‘better means’ should be was never clearly spelled out, but it didn’t matter then. ‘F—the System!’ was program enough so long as it left room for lots of sex and drugs and rock and roll. ‘He used to say, ‘All I care about is who’s bringing the ice cream to the demonstration,’ recalls fellow yippie Jerry Rubin, 50. ‘Essentially, he wanted to have fun.’

Now, those alienated young people are no longer young, and Woodstock Nation is a memory. But ‘Abbie wasn’t interested in nostalgia,’ says Al Giordano, 29, a journalist who knew him well. ‘He was interested in battling the power structure. He had learned that nostalgia is just another form of depression.’

The last thing Hoffman needed was more forms of depression.”

__________________________

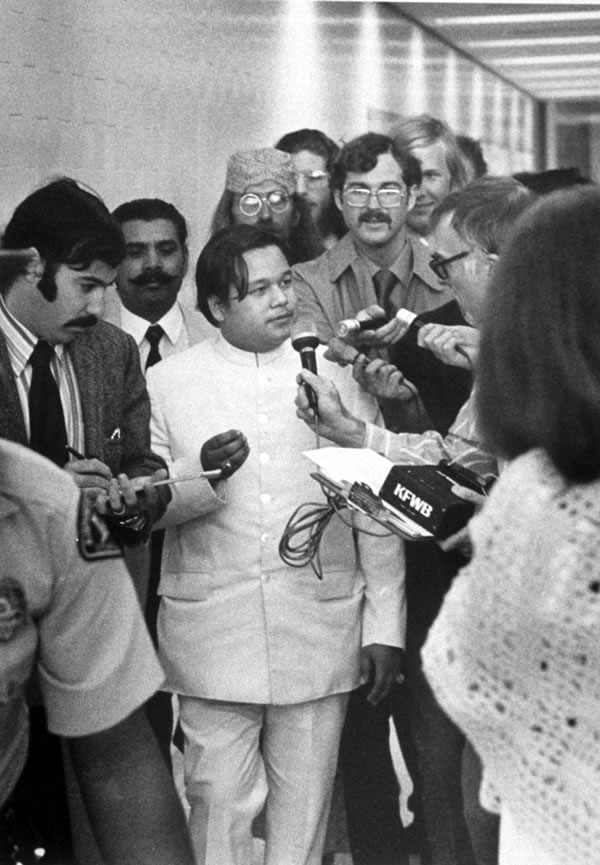

Abbie makes gefilte fish, 1973: