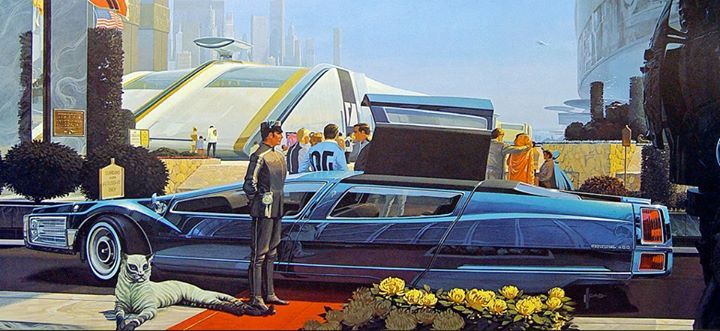

An excerpt from “Future of Rail 2050,” an ARUP study which predicts the demands of sprawling megacities will completely overhaul the nature of railway stations and that the typical person will be named “Nuno”:

“Hugo Dupont, 31 • Smart City Engineer

Hugo is rushing to catch the Metro train to work. Earlier, as he reached Rue Daval, he remembered that he had left a parcel on his kitchen counter and had to turn back to get it. Now, running a little late but parcel in hand, he pauses as a fleet of driverless pods pass by and then crosses the road at the signal, disappearing into the Metro station.

He needs the package to be delivered that evening, as today is his friend Nuno’s birthday. At the entrance to the Metro, he drops the parcel into the International Express box next to the interactive tourist information wall. As he selects to receive freight alerts to track the progress of his package and pays for the shipping with a tap of a button, a message notifies him that his meeting with colleagues in Hong Kong via holographic software will start in 15 minutes. He hurries to the platform to catch his train.

The platform screen doors slide shut just before Hugo can board the Metro. However, he isn’t too worried as he knows the next train will arrive in under a minute. The driverless metro trains can travel in close succession as they constantly communicate with each other and with rail infrastructure and automatically respond to the movements of the other trains on the track, making the metro extremely safe and efficient.

As he waits, Hugo notices other commuters buying groceries from the virtual shopping wall. As his fridge hasn’t sent him any alerts, he thinks he is stocked up well enough at home for the time being. He also glances at some of the artwork on platform screen doors — he enjoys seeing the changing digital exhibitions every day.

Meanwhile, at 08:46, Hugo’s parcel drops onto a conveyor belt and is transported to a pod on the underground freight pipeline. The routing code is scanned as it is loaded onto the pod, and the package is whisked away to Gare Centrale. The electric pod travels uninhibited at a steady pace, independent of traffic and weather conditions, and at 09:16 the package is loaded onto the mail carriage at the back of the waiting high-speed EuroTrain that carries both passengers and small express freight. At 10:35, the train leaves the station and runs directly to Berlin.

In his office, Hugo is testing a new system for analysing how much electricity from braking trains is fed back into the grid, when he receives a notification informing him that his package is on the train and is running on schedule. Hugo lives alone in an apartment in a large European megacity. Having studied abroad, he has returned to his home city and works as a Smart City Engineer for the City Authority, maintaining a network of sensors tracking electricity, traffic and people flows to create efficiencies across city systems. He likes gadgets and his wearable computers perform a variety of functions from wayfinding, to holographic communication, to the real-time monitoring of his health.”