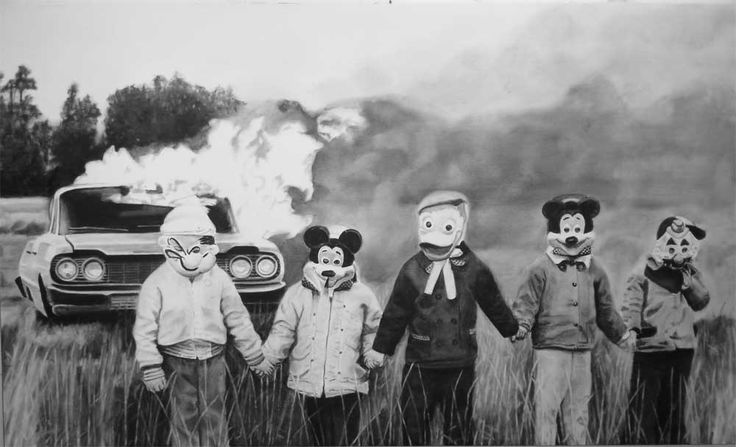

In the future, you will never be alone again. Never.

Prelude to the Internet of Things, when nearly every last object will be a computer and society a machine with no OFF switch, is today’s proliferation of sensors and cameras, making their way into private homes as well as public spaces. You may barely notice them, which is the idea.

I doubt, though, most would care even if aware that the Roomba is doing a constant sweep for information and the TV may also be watching them. So many have willingly surrendered the most intimate details in exchange for a “friend” or a “like.” We essentially gleefully gave away what was always feared would be taken from us. We’ve acquiesced to a “soft” totalitarianism.

What the Internet Era of Silicon Valley has perhaps done best of all is locating and massaging the psychological weak spots of their customers who crave not only convenience and “free” services but also attention. That they’ve divined unobtrusive ways to simultaneously follow and search us is a big part of the bargain. It’s out of sight, out of mind.

Three excerpts follow.

____________________________

From Maggie Astor at the New York Times:

Your Roomba may be vacuuming up more than you think.

High-end models of Roomba, iRobot’s robotic vacuum, collect data as they clean, identifying the locations of your walls and furniture. This helps them avoid crashing into your couch, but it also creates a map of your home that iRobot is considering selling to Amazon, Apple or Google.

Colin Angle, chief executive of iRobot, told Reuters that a deal could come in the next two years, though iRobot said in a statement on Tuesday: “We have not formed any plans to sell data.”

In the hands of a company like Amazon, Apple or Google, that data could fuel new “smart” home products.

“When we think about ‘what is supposed to happen’ when I enter a room, everything depends on the room at a foundational level knowing what is in it,” an iRobot spokesman said in a written response to questions. “In order to ‘do the right thing’ when you say ‘turn on the lights,’ the room must know what lights it has to turn on. Same thing for music, TV, heat, blinds, the stove, coffee machines, fans, gaming consoles, smart picture frames or robot pets.”

But the data, if sold, could also be a windfall for marketers, and the implications are easy to imagine. No armchair in your living room? You might see ads for armchairs next time you open Facebook. Did your Roomba detect signs of a baby? Advertisers might target you accordingly. …

Albert Gidari, director of privacy at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society, said that if iRobot did sell the data, it would raise a variety of legal questions.

What happens if a Roomba user consents to the data collection and later sells his or her home — especially furnished — and now the buyers of the data have a map of a home that belongs to someone who didn’t consent, Mr. Gidari asked. How long is the data kept? If the house burns down, can the insurance company obtain the data and use it to identify possible causes? Can the police use it after a robbery?•

____________________________

From Devin Coldewey at Techcrunch:

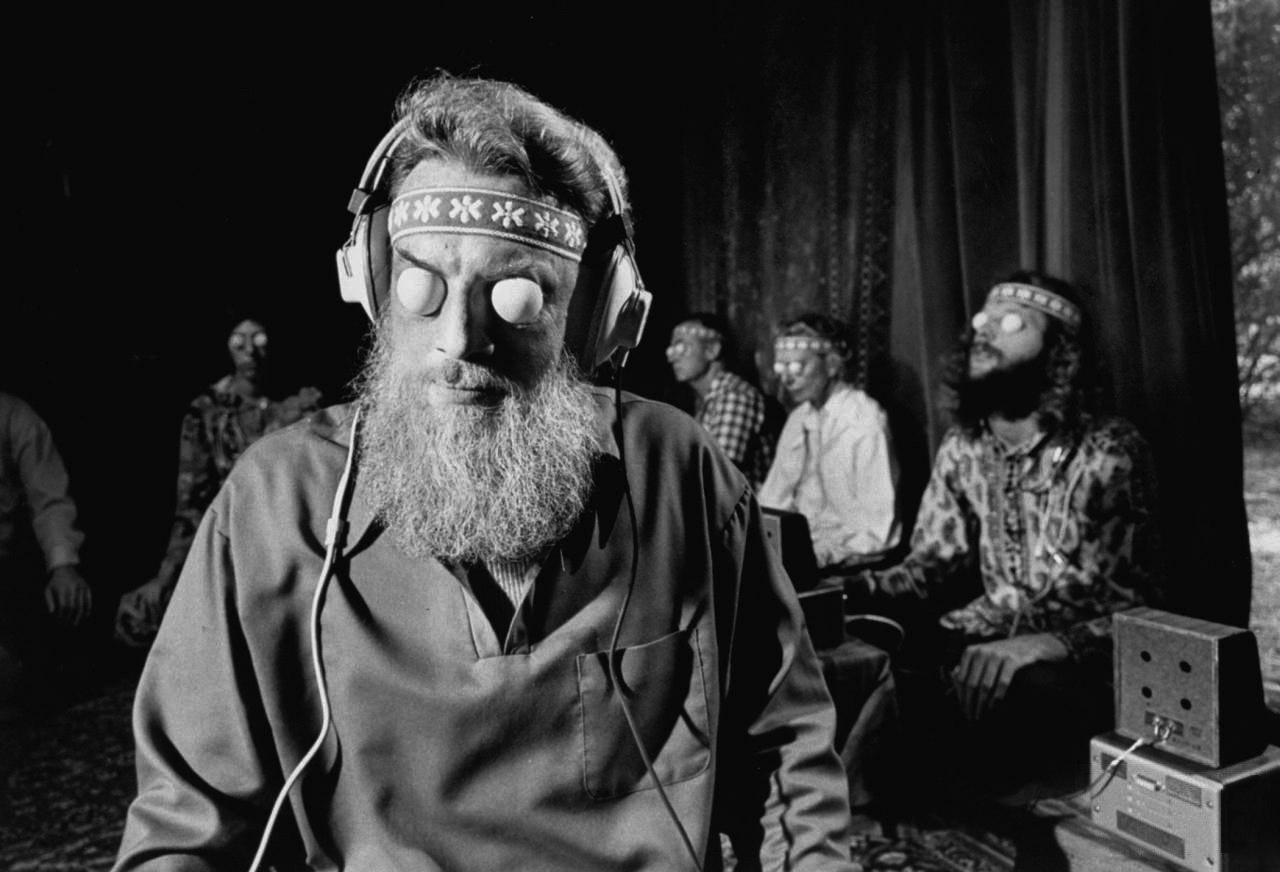

As moviemaking becomes as much a science as an art, the moviemakers need to ever-better ways to gauge audience reactions. Did they enjoy it? How much… exactly? At minute 42? A system from Caltech and Disney Research uses a facial expression tracking neural network to learn and predict how members of the audience react, perhaps setting the stage for a new generation of Nielsen ratings.

The research project, just presented at IEEE’s Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition conference in Hawaii, demonstrates a new method by which facial expressions in a theater can be reliably and relatively simply tracked in real time.

It uses what’s called a factorized variational autoencoder — the math of it I am not even going to try to explain, but it’s better than existing methods at capturing the essence of complex things like faces in motion. …

Of course, this is just one application of a technology like this — it could be applied in other situations like monitoring crowds, or elsewhere interpreting complex visual data in real time.•

____________________________

The opening of David Pierce’s Wired piece “Inside Andy Rubin’s Quest To Create an OS For Everything“:

Here’s some free advice: Don’t try to break into Andy Rubin’s house. As soon as your car turns into the driveway at his sprawling pad in the Silicon Valley hills, a camera will snap a photo of your vehicle, run it through computer-vision software to extract the plate number, and file it into a database. Rubin’s system can be set to text him every time a certain car shows up or to let specific vehicles through the gate. Thirty-odd other cameras survey almost every corner of the property, and Rubin can pull them up in a web browser, watching the real-time grid like Lucius Fox surveying Gotham from the Batcave. If by some miracle you were to make it all the way to the front door, you’d never get past the retinal scanner.

Rubin doesn’t employ human security guards. He doesn’t think he needs them. The 54-year-old tech visionary (who, among other things, coinvented Android) is pretty sure he has the world’s smartest house. The homebrew security net is only the beginning: There’s also a heating and ventilating system that takes excess heat from various rooms and automatically routes it into cooler areas. He has a wireless music system, a Crestron custom-install home automation system, and an automatic cleaner for his pool.

Getting the whole place up and running took Rubin a decade. And don’t even ask him what it cost. There’s an entire room full of things he bought, tried, and shelved, but the part that really drove him crazy was that it didn’t seem like automating his home ought to be this hard. Take the license-plate camera, for instance: Computer-vision software that can read a tag is readily available. Outdoor cameras are cheap and easy to find, as are infrared illuminators that let those cameras see in the dark. Self-opening gates are everywhere. All the pieces were available, but “they were all by different companies,” Rubin says. “And there was no UI. It’s not turnkey.”

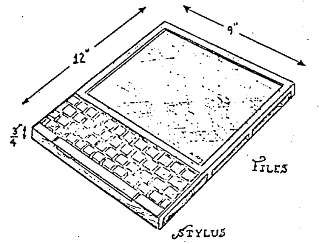

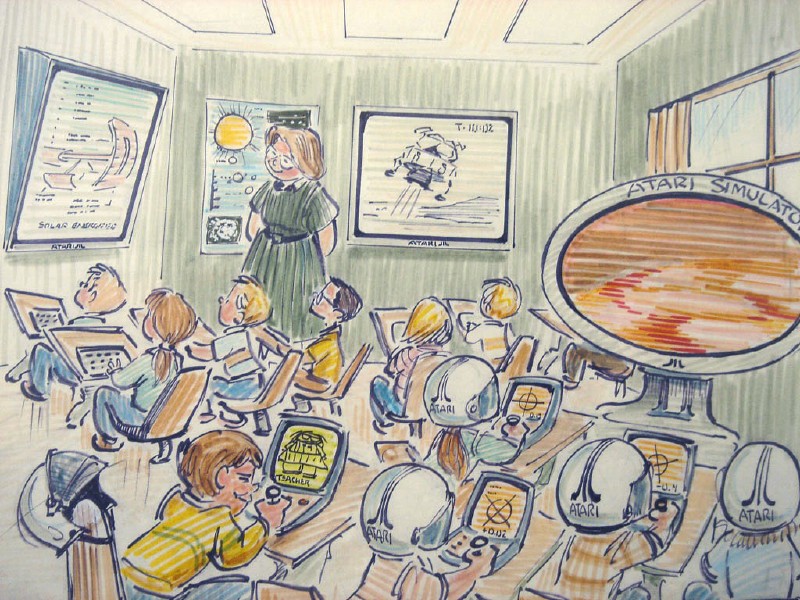

At some point during his renovations, Rubin realized he was experiencing more than just rich-guy gadget problems. He was too far ahead of the curve. If anything, the problem is about to get much worse: The price and size of a Wi-Fi radio and microprocessor are both falling toward zero; wireless bandwidth is more plentiful and reliable; batteries last longer; sensors are more accurate; software is more reliable and more easily updated. As many as 200 billion new internet-connected devices are predicted to be online in just the next few years. Phones and tablets, certainly. But also light bulbs and doorknobs, shoes and sofa cushions, washing machines and showerheads.

In many cases, the effects of these connected devices will be invisible: better temperature optimization in warehouses or super-efficient routes for UPS drivers. But at the same time, all those freshly awake devices will present an entirely new way to interact with the world around you.•