Some people search and find the wrong thing.

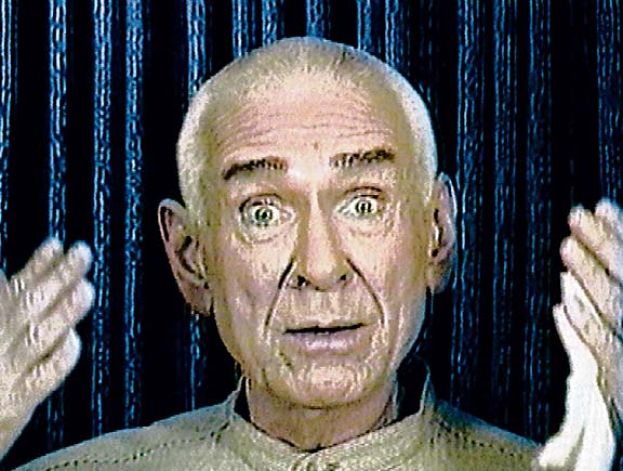

Such was the case with the followers of the technologically friendly cult Heaven’s Gate, which stunned the world when 38 members committed a mass suicide in 1997 at the behest of the group’s leader Marshall Applewhite, a bisexual man deeply troubled by his orientation, who founded the pseudo-religion 22 years earlier in Los Angeles. The guru believed the Hale-Bopp Comet would be tailed by a UFO which would take them to heaven if they killed themselves at just the right moment, and somehow a diverse group of basically intelligent people heeded his call.

I thought of this sad and strange chapter from America’s recent past (on another sad and strange day) when I came across Fiona Sturges’ Financial Times report on the new podcast series Cults, which covers Heaven’s Gate and other dangerous group dynamics. It reminds that the stories we tell ourselves as small clans or large nations can sustain life or get plenty of us killed. That’s why we need to be sane and rational about the narratives we choose.

Just after the mass death 20 years ago, People magazine profiled Applewhite and some of his acolytes. An excerpt:

Marshall Herff Applewhite 65, music teacher turned cult leader

Missouri prosecutor Tim Braun never forgot the car-theft case that came his way in 1974, when he was a novice St. Louis County public defender. “Very seldom do we see a statement that ‘a force from beyond the earth has made me keep this car,’ ” he says. The defendant: Marshall Herff Applewhite. The sentence: four months in jail.

His early life offers few hints of what led Applewhite—son of a Presbyterian preacher and his wife—to abandon his career as a music professor for a life chasing alien spacecraft. Married with two children, he seemed the devoted family man. But his marriage broke up in the mid-’60s, and he moved to Houston, where he ran a small Catholic college’s music department and often sang with the Houston Grand Opera.

A sharp dresser whose taste in cars ran to convertibles, and in liquor to vodka gimlets, he became a fixture of Houston’s arts scene—and, less overtly, its gay community. “Everybody knew Herff,” says Houston gay activist and radio host Ray Hill. But in 1970, Applewhite left the college, apparently after allegations of an affair with a male student.

Soon afterward, Houston artist Hayes Parker recalls, Applewhite claimed to have had a vision during a walk on the beach in Galveston, Texas. “He said he suddenly had knowledge about the world,” recalls Parker. Around that time he met nurse Bonnie Nettles, with whom he formed an instant bond that became the basis of a 25-year cult odyssey. They wandered the country, gathering followers and attracting so much curiosity that by the mid-’70s he had been interviewed by The New York Times. “Some people are like lemmings who rush in a pack into the sea,” Applewhite said of other alternative lifestyles. “Some people will try anything.”

· · ·

Cheryl Butcher 42, computer trainer

Butcher was a shy, bright, self-taught computer expert who spent half her life in Applewhite’s orbit. Growing up in Springfield, Mo., she was “the perfect daughter,” says her father, Jasper, a retired federal corrections officer. “She was a good student. She did charity work, candy striper stuff.” But according to Virginia Norton, her mother, she was also “a loner. She watched a lot of TV and read. Making friends was hard for her.” That is, until she joined the cult in 1976. “She wrote me a letter once,” says Norton, “that said, ‘Mother, be happy that I’m happy.’ Another time she ended a letter with ‘Look higher.’ “

· · ·

David Van Sinderen 48, environmentalist

“When I was 4, he saved me from drowning,” says publicist Sylvia Abbate of her big brother David. The son of a former telephone company CEO, David became an environmentalist. ” ‘Don’t be hurt, I’m not doing this to you,’ ” Abbate says he told his family after he joined the cult in 1976. ” ‘It’s something I have to do for me.’ ” Visiting his sister in ’87, he puzzled her with his backseat driving, then apologized, explaining that cult members drove with a partner so they would have an extra set of eyes. Says Abbate: “That’s the kind of care they had for one another.”· · ·

Alan Bowers 45, oysterman

Bowers had spent eight years with the cult in the ’70s before returning to Fairfield, Conn., in the early ’80s to work as a commercial oysterman. In 1988 his life derailed when his wife divorced him and his brother Barry drowned in a boating accident. Bowers, who had three children, moved to Jupiter, Fla., near his stepsisters Susan and Joy Ventulett. “He came down here to make a new start,” says Susan, but he could never quite get it together. Then in 1994, Bowers, while working for a moving company, ran into someone he knew from Applewhite’s legions at a McDonald’s in New Mexico. “He felt it might have been destiny,” says Joy. “He was a little vulnerable. He was searching for peace.”· · ·

Margaret Bull 54, farm girl

Peggy Bull, among the cult’s first adherents in the mid-’70s, grew up on a farm outside little Ellensburg, Wash. Though shy, she was in the high school pep club and a member of the Wranglerettes, a riding drill team. Later “she belonged to all the intellectual-type groups,” says Brenda McIntosh, a roommate at the University of Washington, where Bull earned her B.A. in 1966. “It was sometimes hard to talk to her because she was so smart.” Recalls English professor Roger Sale: “She was a open and ready intellectually.” Her father, Jack, died less than three weeks before Bull’s suicide, says Margaret’s childhood friend Iris Rominger, who assumed that Bull had left the cult. “I guess it’s kind of a blessing.”•