In Henry Miller’s The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, first published in America in 1945, the expat author returns to his native land to occasionally admire the beauty but to mostly spit on the dirt. You could say that the writer was great at finding ugliness anywhere he roamed in the U.S., much the same way that Joan Didion always recognized looming collapse no matter where she landed–both were good at projecting the disquiet within onto any landscape–except that Miller took deep appreciation in many things, often hidden pieces of culture and art and history that delighted him. The book is largely a success, apart for the author’s boneheaded appreciation for the great things that a slave culture can produce.

In Henry Miller’s The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, first published in America in 1945, the expat author returns to his native land to occasionally admire the beauty but to mostly spit on the dirt. You could say that the writer was great at finding ugliness anywhere he roamed in the U.S., much the same way that Joan Didion always recognized looming collapse no matter where she landed–both were good at projecting the disquiet within onto any landscape–except that Miller took deep appreciation in many things, often hidden pieces of culture and art and history that delighted him. The book is largely a success, apart for the author’s boneheaded appreciation for the great things that a slave culture can produce.

Here are three passages of Miller’s darkest, most apocalyptic thoughts about humanity as it moved into a modern, technological age, the first two from the books’ preface and the third from the chapter “With Edgard Varèse in the Gobi Desert”:

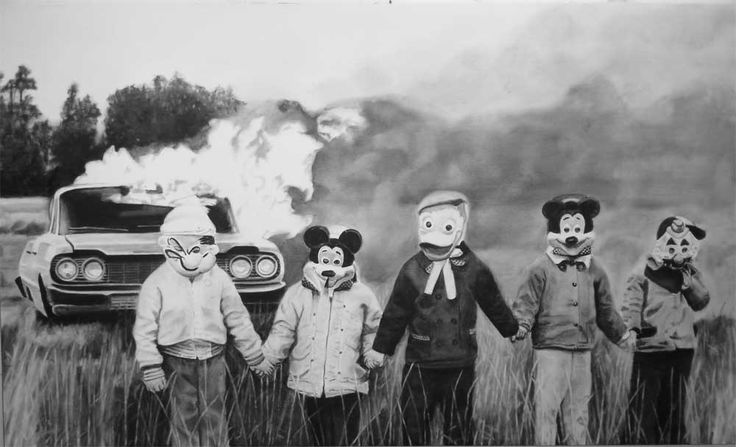

As to whether I have been deceived, disillusioned…The answer is yes, I suppose. I had the misfortune to be nourished by the dreams and visions of great Americans–the poets and seers. Some other breed of man has won out. This world which is in the making fills me with dread. I have seen it germinate; I can read it like a blue-print. It is not a world I want to live in. It is a world suited for monomaniacs obsessed with the idea of progress–but a false progress, a progress which stinks. It is a world cluttered with useless objects which men and women, in order to be exploited and degraded, are taught to regard as useful. The dreamer whose dreams are non-utilitarian has no place in this world. Whatever does not lend itself to being bought and sold, whether in the realm of things, ideas, principles, dreams or hopes, is debarred. In this world the poet is anathema, the thinker a fool, the artist as escapist, the man of vision a criminal. …

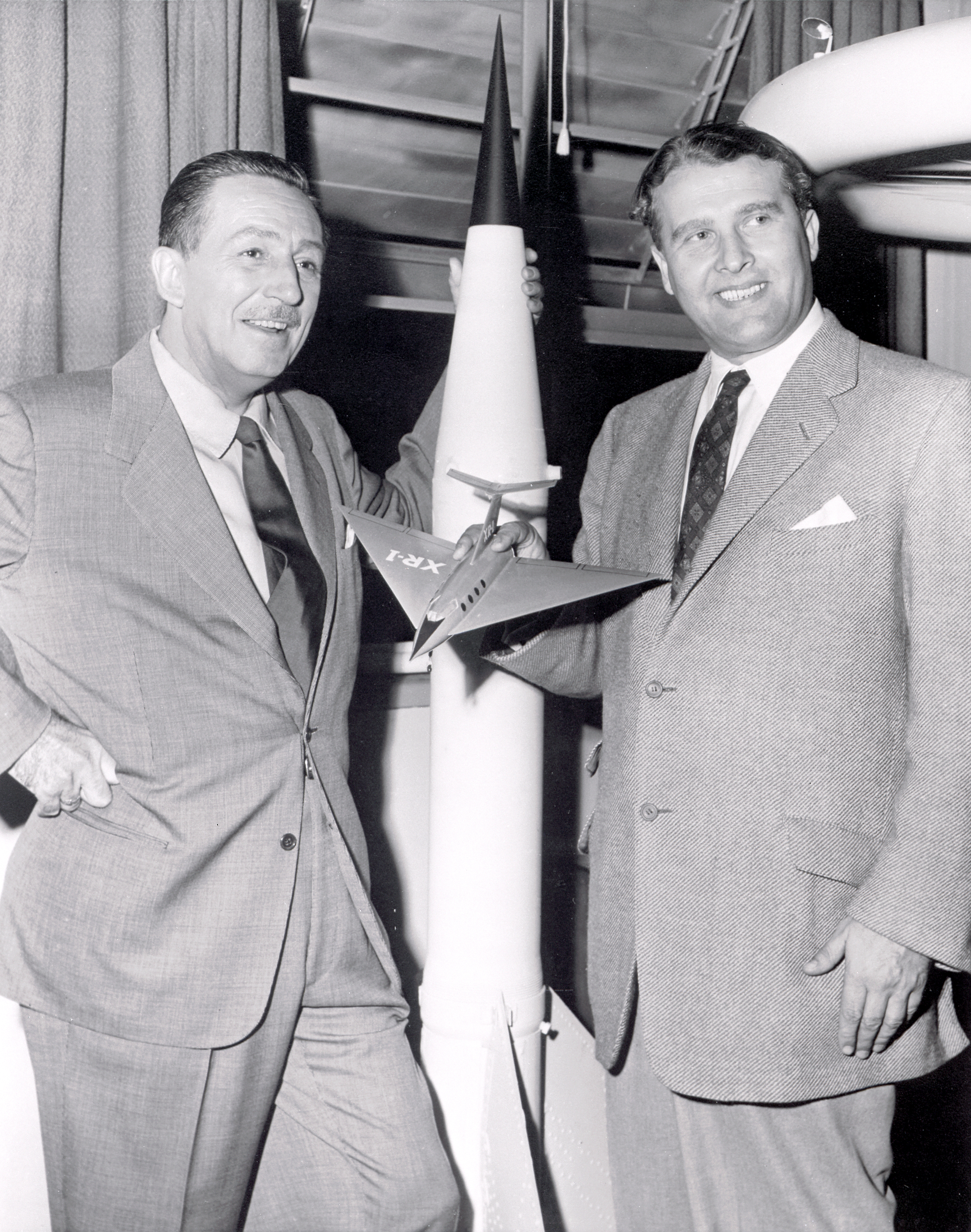

Disney works fast–like greased lightning. That’s how we’ll all operate soon. What we dream we become. We’ll get the knack of it soon. We’ll learn how to annihilate the whole planet in the wink of an eye–just wait and see. ..

To-morrow all that we take for granted may wear a new face. New York may come to resemble Petra, the cursed city of Arabia. The corn fields may look like a desert. The inhabitants of our cities may be obliged to take to the woods and grub for food on all fours, like animals. It is not impossible. It is even quite probable. No part of this planet is immune once the spirit of self-destruction takes hold. The great organism called Society may break down into molecules and atoms; there may not be a vestige of any social form which could be called a body. What we call “society” may become one interrupted dissonance for which no resolving chord will ever be found. That too is possible.

We know only a small fraction of the history of man on this earth. It is a long, tedious painful record of catastrophic changes involving the disappearance of whole continents sometimes. We tell the story as though man were an innocent victim, a helpless participant in the erratic and unpredictable revolutions of Nature. Perhaps in the past he was. But not any longer. Whatever happens to this earth to-day is of man’s doing. Man has demonstrated that he is master of everything–except of his own nature. If yesterday he was a child of nature, to-day he is a responsible creature. He has reached a point of consciousness which permits him to lie to himself no longer. Destruction is now deliberate, voluntary, self-induced. We are at the node: we can go forward or relapse. We still have the power of choice. To-morrow we may not. It is because we refuse to make the choice that we are ridden with guilt, all of us, those who are making war and those who are not. We are all filled with murder. We loathe one another. We hate what we look like when we look into one another’s eyes.

What is the magic word for this moment?•