In 2011, I quoted something from Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels:

The Angels don’t like to be called losers, but they have learned to live with it. “Yeah, I guess I am,” said one. “But you’re looking at one loser who’s going to make a hell of a scene on the way out.”

It’s an odd outcome because the Angels emerged from America’s great triumph in World War II, as it and other motorcycle gangs were formed from the wanderlust of our war vets. But the love of the road turned into hatred for the self, and then, the other.

Five years ago when I published that excerpt, I was more concerned about militias and a scary strain of right-wing backlash that seemed awakened by the election of our first African-American President and gains made by women and other minorities. I never expected those on the fringes to make such gains on the center–to win it. And I’m not exactly someone who spends my idle time at Berkeley cocktail parties.

The ones who wanted to make America white again formed a faction with those who felt adrift in the modern economy, with its wealth inequality and bruising technological shift. The latter group had always looked on others as the “losers” and didn’t want to join them, even if the scoreboard said they already had. Together the haters and the backsliders made a hell of a scene in 2016.

From Susan McWilliams’ Nation piece about Thompson forecasting the rise of Trumpism:

It has been 50 years since Hunter S. Thompson published the definitive book on motorcycle guys: Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs. It grew out of a piece first published in The Nation one year earlier. My grandfather, Carey McWilliams, editor of the magazine from 1955 to 1975, commissioned the piece from Thompson—it was the gonzo journalist’s first big break, and the beginning of a friendship between the two men that would last until my grandfather died in 1980. Because of that family connection, I had long known that Hell’s Angels was a political book. Even so, I was surprised, when I finally picked it up a few years ago, by how prophetic Thompson is and how eerily he anticipates 21st-century American politics. This year, when people asked me what I thought of the election, I kept telling them to read Hell’s Angels.

Most people read Hell’s Angels for the lurid stories of sex and drugs. But that misses the point entirely. What’s truly shocking about reading the book today is how well Thompson foresaw the retaliatory, right-wing politics that now goes by the name of Trumpism. After following the motorcycle guys around for months, Thompson concluded that the most striking thing about them was not their hedonism but their “ethic of total retaliation” against a technologically advanced and economically changing America in which they felt they’d been counted out and left behind. Thompson saw the appeal of that retaliatory ethic. He claimed that a small part of every human being longs to burn it all down, especially when faced with great and impersonal powers that seem hostile to your very existence. In the United States, a place of ever greater and more impersonal powers, the ethic of total retaliation was likely to catch on.

What made that outcome almost certain, Thompson thought, was the obliviousness of Berkeley, California, types who, from the safety of their cocktail parties, imagined that they understood and represented the downtrodden. The Berkeley types, Thompson thought, were not going to realize how presumptuous they had been until the downtrodden broke into one of those cocktail parties and embarked on a campaign of rape, pillage, and slaughter.•

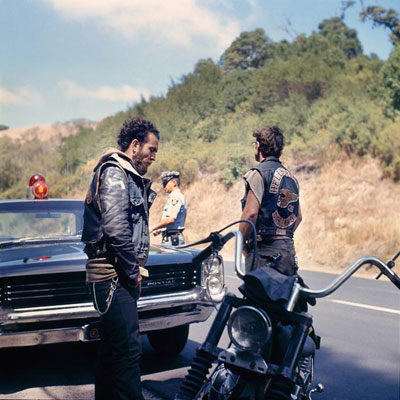

Sonny Barger terrorizes Thompson in 1967 on Canadian TV.

Ad for Hunter S. Thompson’s campaign for Sheriff of Aspen in 1970.

Tags: Susan McWilliams