In a smart Five Books interview, Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of Oneida, discusses a group of titles on the topic of Utopia. She surmises that attempts at such communities aren’t prevalent like they were in the 1840s or even the 1960s because most of us realize they don’t normally end well, whether we’re talking about the bitter financial and organizational failures of Fruitlands and Brook Farm or the utter madness of Jonestown. That’s true on a micro-community level, though I would argue that there have never been more people dreaming of large-scale Utopias–and corresponding dystopias–then there are right now. The visions have just grown significantly in scope.

In macro visions, Silicon Valley technologists speak today of an approaching post-scarcity society, an automated, quantified, work-free world in which all basic needs are met and drudgery has disappeared into a string of zeros and ones. These thoughts were once the talking points of those on the fringe, say, a teenage guru who believed he could levitate the Houston Astrodome, but now they (and Mars settlements, a-mortality and the computerization of every object) are on the tongues of the most important business people of our day, billionaires who hope to shape the Earth and beyond into a Shangri-La.

Perhaps much good will come from these goals, and maybe a few disasters will be enabled as well.

One exchange from the Five Books Q&A:

Question:

Speaking of the Second Coming, the last book on your list is Paradise Now, by Chris Jennings.

Ellen Wayland-Smith:

It’s called Paradise Now: The Story of American Utopianism. He goes through five utopian experiments in nineteenth century America. It’s a beautifully written book and interesting as well because he takes the odd era of 1840s America and shows how it gave rise to five very different experiments in alternative living. He does a sensitive job of exploring their differences and similarities but he also examines how crazy they seem today. Some of the ideas seem mystical and fabulous; certainly Noyes had some spectacularly strange ideas about gaining immortality through sexual intercourse. The fact that so many of these strange communities sprung up seems unbelievable to the twenty-first century reader. Chris Jennings points out that we seem to have lost something, there seems to be a diminishment of expectations, a loss of energy.

Question:

In the wake of the American Revolution over a hundred experimental communities were formed in the United States. Do societies become less experimental as they age into their institutions? Is the West losing the audacity necessary for experimentation?

Ellen Wayland-Smith:

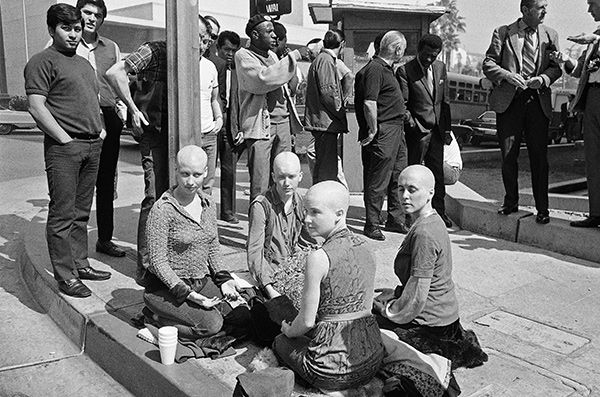

That is an interesting question. The 1840s were an incredibly weird time. It was a crossroads. It was the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Class identification and geographical identification suddenly became uncertain, that was upsetting. There were also an explosion of religious sects at this time, with the disestablishment of state and church. I think it was a time when people felt very vulnerable. All these changes and uncertainties crystallized attempts to live otherwise.

Question:

Jennings writes that a present day “deficit of imagination” accounts for the fact that there are no utopias at present. Do you see a strong foundation for that analysis?

Ellen Wayland-Smith:

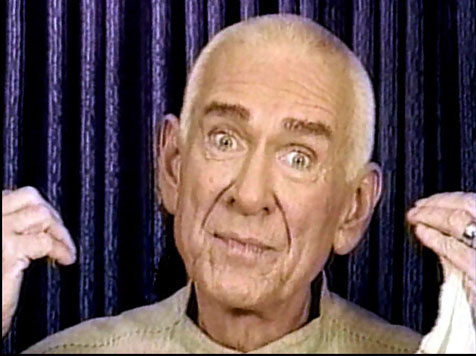

There does seem to be a lack of interest in what is transcendent, which keeps people from finding more meaningful ways of constructing their lives. But what accounts for the absence of utopian schemes at present is probably less a ‘deficit of imagination’ than a cynicism about whether these things can work. As I began by saying, utopian projects usually end disastrously.•