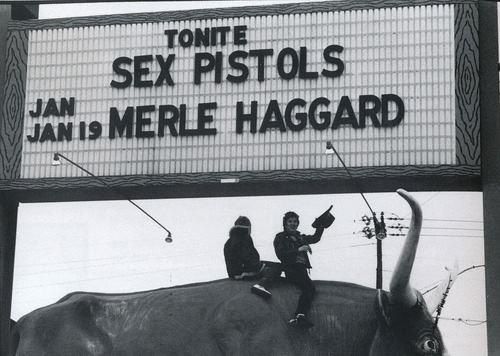

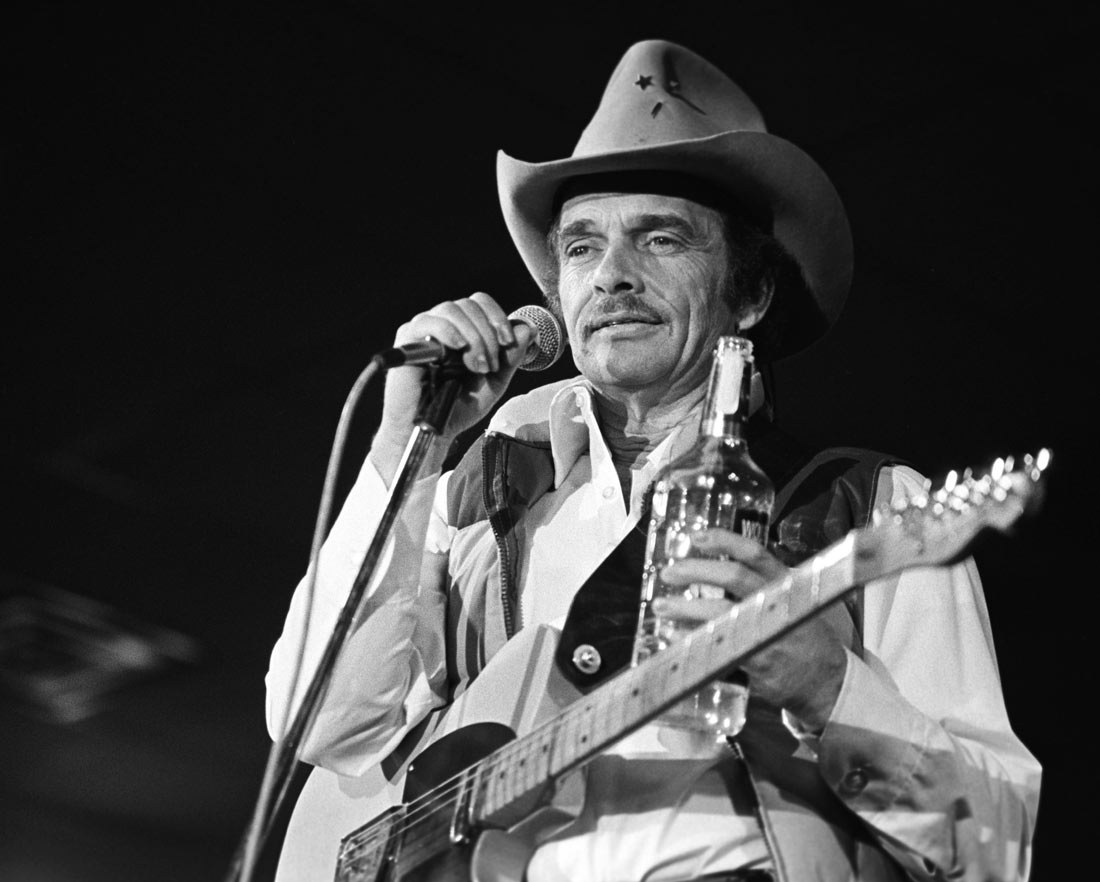

Merle Haggard had a rebellious streak.

The recently deceased musician’s son-of-an-Okie orneriness drove him to shuck off respectability piece by piece: family, school, law and even the Lord Himself. Those outlaw impulses also helped him birth the mutinous Bakersfield sound, which gave a lift to country’s dog-beat blues and later made him breathe fire when slick production forced too much sunlight into the genre.

The Village Voice, which laid off Nat Hentoff in 2008 under previous ownership, has republished the music critic’s great 1980 profile of Haggard. The Voice can never be what it once was because, let’s face it, the paper was born of a literary culture that’s now much diminished, but with an ambitious, new owner and some good hires, it looks like it can still be a valuable thing.

The opening:

The story is that he has a spider web tattooed on his back. “He did it when he was young and felt trapped,” Bonnie Owens once told the Southern writer and good listener, Paul Hemphill.

Merle Haggard was the child of Okies who had been farmers near Checotah, Oklahoma, not far from the Muskogee. After a disastrous fire, there came a drought, and so Merle’s folks (he hadn’t come on the scene yet) went off to California where, as Jimmie Rodgers sang, “they sleep out every night.”

James Haggard had been a pretty fair fiddler and picker back in Oklahoma; but his wife, Flossie, once her soul took fire in the Church of Christ, banned him from playing the devil’s music. All the more so since another child, Merle, had been born to be reared in a straight line to the Saviour. The Haggards were living in a converted refrigerator car near Bakersfield, California, by then; and James, now a carpenter with the railroad, taught the boy fishing and hunting. But when Merle was nine, his father, as Merle later put it, abandoned him. The interviewer asked if he’d be a little more specific.

“He died,” said Merle.

“Mama Tried,” as Haggard later titled a song, but she failed. She could not control the boy. He ran away a lot; cut school (finally dropping out in the eighth grade); and became quite familiar to the Bakersfield police. When Merle was 14, Flossie put him in a juvenile home, and he escaped the next day. Merle’s police record grew like Pinocchio’s nose–bum checks, petty thievery, a stolen car, armed robbery. Reform schools couldn’t hold him. Seven times he slid out of them. But when he and some of the boys messed up the burglary of a Bakersfield bar (they got drunk waiting for the bar to close), he got sent to a place that could hold him. San Quentin.•

Tags: Merle Haggard, Nat Hentoff