Hanna Reitsch would have been a feminist hero, if it weren’t for the Nazism.

Like the equally talented Leni Riefenstahl, politics made her story the thorniest thing. Reitsch was a pioneering, early-20th-century test pilot, an aviatrix as she was called in that era, but her gifts and great daring were used in the service of the Nazi Party beginning in the 1930s. Her importance in the scheme of things was such that she visited Hitler in his bunker in 1945.

Although her reputation was always sullied—and, of course, should have been—Reitsch nonetheless did enjoy considerable standing despite her past, becoming a champion glider, and even being invited as a guest of the White House during the Kennedy Administration.

The text of “Girl Rode Robot Bomb To Test It, Nazis Reveal,” the July 27, 1944 Brooklyn Daily Eagle account of her most storied and dangerous mission, for which she received the Iron Cross:

In 1976, three years before her death, Reitsch was interviewed about her aerial exploits.

__________________________

Even though he remains one of the pantheon filmmakers, Fritz Lang had mixed feelings about the medium. Talkies initially left him cold and later on he found the Hollywood studio system a discombobulating compromise.

In 1972, Lang was interviewed by two reporters, Lloyd Chesley and Michael Gould, and confided in them that he had tired of directing movies by the advent of talking pictures and decided to recreate himself as a chemist. A disreputable money man dragged him back into the business and gave him the creative freedom to make the chilling classic, M. An excerpt from the interview:

Michael Gould:

Your themes changed from epic to intimate when you began making sound films.

Fritz Lang:

I got tired from the big films. I didn’t want to make films anymore. I wanted to become a chemist. About this time an independent man—not of very good reputation—wanted me to make a film and I said ‘No, I don’t want to make films anymore.’ And he came and came and came, and finally I said ‘Look, I will make a film, but you will have nothing to say for it. You don’t know what it will be, you have no right to cut it, you only can give the money.’ He said ‘Fine, understood.’ And so I made M.

We started to write the script and I talked with my wife, Thea von Harbou, and I said ‘What is the most insidious crime?’ We came to the fact of anonymous poison letters. And then one day I said I had another idea—long before this mass murderer, [Peter] Kurten, in the Rhineland. And if I wouldn’t have the agreement for no one to tell me anything, I would never, never have made M. Nobody knew Peter Lorre.•

In 1975, Lang and William Friedkin, two directors transfixed by extreme evil, engaged in conversation.

__________________________

John Cale sometimes seems exhausted talking about The Velvet Underground, and who could blame him? An unlikely rock star to begin with, the Welsh musician was a classically trained violinist with strong avant garde leanings who arrived in New York City just as its rock and art scenes were exploding into one another, collaborating almost immediately with volatile Lou Reed and soon enough vampiric Andy Warhol. Cale lasted two albums with the band, but has never escaped its reputation. How could he?

Some reminiscences of the group from his 2012 Guardian interview:

“In Chicago, I was singing lead because Lou had hepatitis, no one knew the difference. We turned our faces to the wall and turned up very loud. Paul Morrissey (later the director of Trash) and Danny Williams had different visions of what the light show should be like and one night I looked up to see them fighting, hitting each other in the middle of a song. Danny Williams just disappeared. They found his clothes by the side of a river, with his car nearby … the whole thing. He used to carry this strobe around with him all the time and no one could figure out why till we found out he kept his amphetamine in it.”

“We worked the Masonic Hall in Columbus Ohio. A huge place filled with people drinking and talking. We tuned up for about ten minutes, tuning, fa-da-da, up, da-da-da, down. There’s a tape of it. Played a whole set to no applause, just silences.”

“In San Francisco, we played the Fillmore and no one liked us much. We put the guitars against the amps, turned up, played percussion and then split. Bill Graham came into the dressing room and said, ‘You owe me 20 more minutes’. I’d dropped a cymbal on Lou’s head and he was bleeding. ‘Is he hurt?’ Graham said, ‘We’re not insured.'”

“Severn Darden brought this young chick up to meet me there and he introduced her as one of my ardent admirers. This was a long time ago and I didn’t know about such things, so I said, ‘Pleased to meet you,’ and walked off. Two days later in L.A., here comes Severn again with this girl. I say hello again and leave. We’re all staying at the castle in L.A., and things are very hazy, if you know what I mean. Well, this girl is there too. I smile but I still don’t understand. About two in the morning the door of my room opens and she walks in naked and gets into bed. Went on for five nights. I don’t think I even got her address.”

The Velvets suffered from all kinds of strange troubles. They spent three years on the road away from New York City, their home, playing Houston, Boston, small towns in Pennsylvania, anywhere that would pay them scale.

“We needed someone like Andy,” John says. “He was a genius for getting publicity. Once we were in Providence to play at the Rhode Island School of Design and they sent a TV newsman to talk to us. Andy did the interview lying on the ground with his head propped up on one arm. There were some studded balls with lights shining on them and when the interviewer asked him why he was on the ground, Andy said, “So I can see the stars better.” The interview ended with the TV guy lying flat on his back saying, “Yeah, I see what you mean.”•

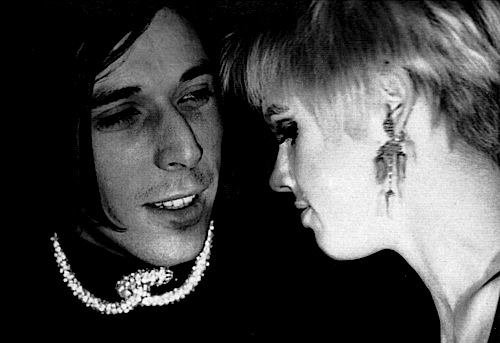

A 21-year-old John Cale the year he arrived in NYC and the one before he met Reed, on I’ve Got a Secret.