Daniel Mendelsohn, who writes beautifully and deeply on pretty much any topic, has a piece in the New York Review of Books about the films Her and Ex Machina, which allows him to drift from times ancient to modern, from Homer’s Greece to Victor Frankenstein’s laboratory to Hollywood’s soundstages, while weighing in on the race between carbon and silicon, a contest we’re certain to lose at least on the micro level. Technological unemployment is less cinematic than the emergence of conscious machines, however, so Strong AI has become the focus of modern storytelling. Mendelsohn wonders why so many of these narratives about “alive” devices revolve around matters of the heart and whether this new “love” means we have surrendered some of our humanness. An excerpt:

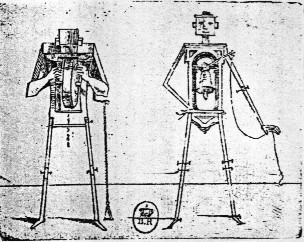

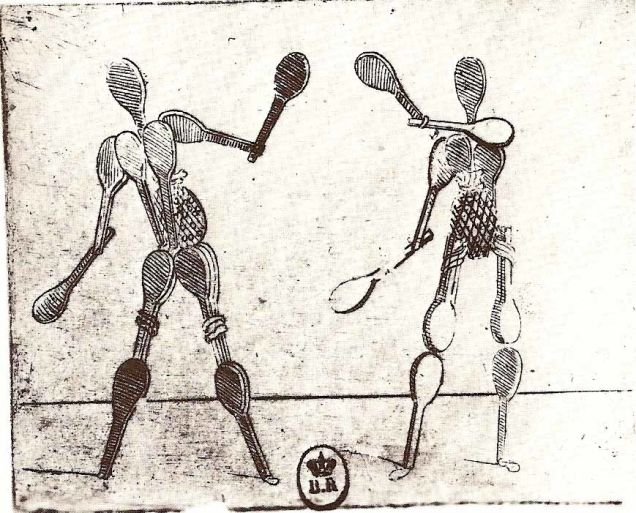

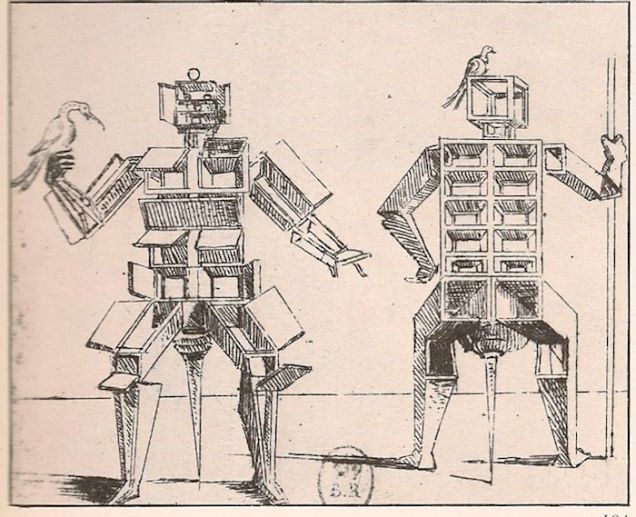

It’s hardly surprising that literary exploitations of this strand of the robot myth began proliferating at the beginning of the nineteenth century—which is to say, when the advent of mechanisms capable of replacing human labor provoked writers to question the increasing cultural fascination with science and the growing role of technology in society: a steam-powered man in Edward Ellis’s Steam Man of the Prairies (1868), an electricity-powered man in Luis Senarens’s Frank Reade and His Electric Man (1885), and an electric woman (built by Thomas Edison!) in Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s The Future Eve (1886). M.L. Campbell’s 1893 “The Automated Maid-of-All-Work” features a programmable female robot: the feminist issue again.

But the progenitor of the genre and by far the most influential work of its kind was Mary Shelley’sFrankenstein(1818), which is characterized by a philosophical spirit and a theological urgency lacking in many of its epigones in both literature and cinema. Part of the novel’s richness lies in the fact that it is self-conscious about both its Greek and its biblical heritage. Its subtitle, “The Modern Prometheus,” alludes, with grudging admiration, to the epistemological daring of its scientist antihero Victor Frankenstein, even as its epigram, from Paradise Lost (“Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay/To mould me man? Did I solicit thee/From darkness to promote me?”) suggests the scope of the moral questions implicit in Victor’s project—questions that Victor himself cannot, or will not, answer. A marked skepticism about the dangers of technology, about the “enticements of science,” is, indeed, evident in the shameful contrast between Victor’s Hephaestus-like technological prowess and his shocking lack of natural human feeling. For he shows no interest in nurturing or providing human comfort to his “child,” who strikes back at his maker with tragic results. A great irony of the novel is that the creation, an unnatural hybrid assembled from “the dissecting room and the slaughter-house,” often seems more human than its human creator.

Just as the Industrial Revolution inspired Frankenstein and its epigones, so has the computer age given rise to a rich new genre of science fiction. The machines that are inspiring this latest wave of science-fiction narratives are much more like Hephaestus’s golden maidens than were the machines that Mary Shelley was familiar with. Computers, after all, are capable of simulating mental as well as physical activities. (Not least, as anyone with an iPhone knows, speech.) It is for this reason that the anxiety about the boundaries between people and machines has taken on new urgency today, when we constantly rely on and interact with machines—indeed, interact with each other by means of machines and their programs: computers, smartphones, social media platforms, social and dating apps.•

Tags: Daniel Mendelsohn